| Print | Back |  |

September 07, 2015 |

|

Moments in Art Genius Short Livedby Lawrence Jeppson |

Giorgio Giorgione died in 1510 at age 32, give or take a few months.

Michelangelo da Caravaggio died a century later, 1610, at 38.

Georges Seurat was the same age when he died in 1891.

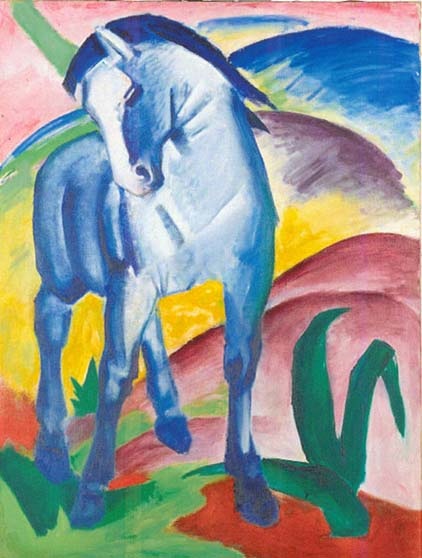

Franz Marc died tragically in 1916 at 36.

Juan Gris’s career was a little longer. He died in 1927 at 40.

All of these men were artistic giants. It boggles the speculative mind to consider what they might have gone on to create had they lived longer.

Giorgione has been called a poet of paint. He was part of the Venetian High Renaissance, a contemporary of Titian. He is probably the rarest known painter in Western art: you can count the number of paintings positively identified as his on your fingers. Probably he perished in the plague.

Caravaggio’s dramatic use of light and realistic depiction of the human condition set him apart and influenced generations of artists. His brushes with the law were as notable as his brushes with paint. He was a thug.

He was jailed from time to time for brawling and fled from city to city. He vandalized his own apartment. In 1606, his death warrant was issued by the Pope after he killed a young man. He died mysteriously, perhaps at the hand of his enemies.

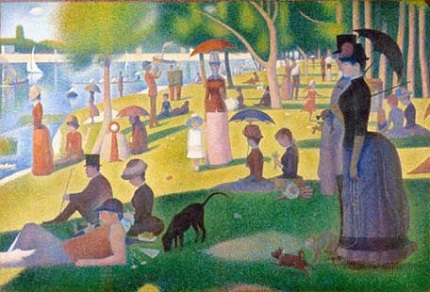

Seurat may have been the most cerebral offshoot of Impressionism. His concern for the technical implications of Impressionism led him to create Pointillism. His very large A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-86) is his most revered painting. It was the inspiration for the Broadway musical An Evening in the Park with George.

I am enamored with the work of Marc. He was part of the group of German painters known as the Blue Riders.

Like most of Germany’s young men during the Great War, he was caught up in Kaiser Wilhelm’s machine. When a list was drawn up of men whose lives should not be put at risk, his name was on it. These men were to be withdrawn from the front. The order came too late. Marc was killed in the bloody, protracted Battle of Verdun.

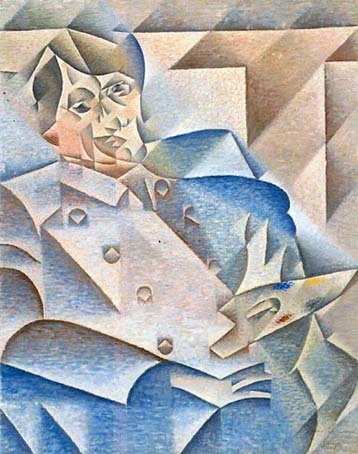

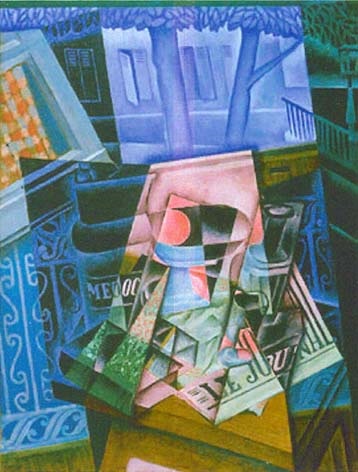

In my previous six “Moments in Art” I have often mentioned Juan Gris, with Picasso and Braque, one of the three most important Cubist painters — and the one whose art I admire most.

Although I am now one of the old guys, in fact, very old guys, I have usually admired men and women who achieve significant things while they are still very young. I suppose in our day such kudos fall to the many geniuses of the dotcom generation. My sensitivity to early achievement goes back to 1940, when I was 14.

My brother Richard was graduating from high school in Carson City, Nevada. The four-year school did not have more than 110 students, Carson City’s population was about 2500, and the population of the entire state topped out, give or take a bit, at 90,000. The commencement talk was given by Nevada’s Deputy Attorney General, Alan Bible. The job was an appointed position. Bible was only 30.

Although I do not recall many of the exact examples, I have never forgotten the gist of Bible’s talk. He ran through example after example of men who had achieved important things while still very young, including Alexander the Great and some of our country’s Founding Fathers.

His talk, of course, was public reassurance that he was capable of his important job at such a young age. He also was laying the groundwork for future political intentions. Two years later he won election as the Attorney General.

Bible went on to serve in the United States Senate, and, as chairman of certain committees, was the de facto mayor of Washington, D.C., when the city was governed by Congress.

Like Picasso, Juan Gris (José Victoriano Gonzalez) came from Spain. Born in Madrid in 1887, he studied mechanical drawing in the School of Arts and Industries. For two years he studied painting under an academic artist, Josè Moreno Carbonero. In 1906, he changed his name to Juan Gris.

To escape military service in 1906, which may be why he changed his name, Gris took off for Paris. There he became friends with painters Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, and Fernand Léger. Still very much an unknown, he was arrested and briefly jailed when police confused him with a member of Bornot’s Band, a group notorious for the political terrorism which swept France as part of a radical workmen’s movement.

Urged by Picasso, he began selling cartoons to several satirical periodicals. Other artists did likewise, but not Picasso, who was wary of confusing his prime artistic intent with this secondary career. He would wait for dealers to knock on his door.

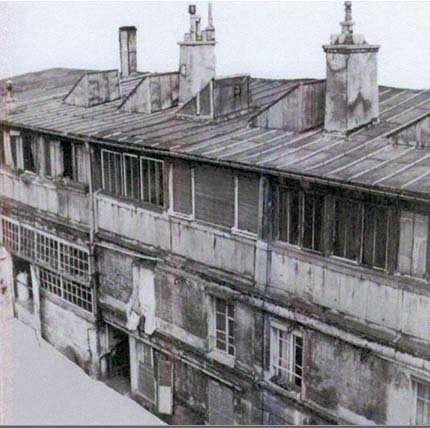

Picasso, Gris, and lots of other struggling artists found living space in a ramshackle wood building cut into the slope of Montmartre. It was built in 1860, and was used for a piano factory.

Because wooden panels divided each floor, creation and alteration of studio and living spaces did not require a great deal of ingenuity. Entrance to everything was from the end of the top floor, which was at street level. Dark corridors and creaky stairs led to the apartments, which were extremely hot in summer and freezing in winter.

There was one toilet for the entire building and water only on the first floor. Every coming and going, noise, song, argument, and scream of passion could be heard throughout the structure.

Picasso called it the Trooper’s House, but because the strange building resembled nothing except, perhaps, the barges on the Seine that housewives used as a place to do their laundry, poet Max Jacob named it the Bateau-Lavoir (Washing Boat). The name stuck.

Gris lived there with his wife. So did other artists, such as Kees van Dongen. It was a difficult life, especially for the women. The men could take refuge in their art, although this was demanding and frustrating — the artist’s perpetual conflict between what he tries to discover about art and about himself in relation to the art, and the need to create something he could paint or sculpt that would sell.

The struggle for the artist to resolve what he would put on canvas is exemplified by Braque’s situation before the creation of Cubism: “He wanted to paint apples like Cézanne, but he was never ever able to paint anything but potatoes.” (A French pun: pommes, apples and pommes de terre, potatoes.)

In 1911, Gris began to paint seriously, developing a personal Cubist style heavily based on mathematics. The next year, 1912, he exhibited in the Salon des Indépendents and signed an exclusive contract with art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler.

As I have written in several previous “Moments in Art” about the dealer, most of his artists went off to fight in World War I. As Spaniards, Picasso and Gris did not. Kahnweiler, being German, took refuge in Switzerland. In the alien reparations auctions after the war, Kahnweiler lost everything. He returned to Paris and opened a new gallery under a different name and tried to persuade back his artists.

Competitor Paul Rosenberg outbid Kahnweiler, and Braque defected. Léger then came to Kahnweiler.

"Rosenberg offers me double what you are paying me."

Kahnweiler replied sadly, "Listen, I'll give you the same amount."

Three months later Léger said, "Paul Rosenberg offers me twice what you are now giving me."

"My dear friend, I believe it is a gross error to jump prices in this fashion, and I cannot do it. Go to Paul Rosenberg."

Gris came to Kahnweiler. "This is what Paul Rosenberg offered me, but believe me, for me it's out of the question."

Gris, in Kahnweiler’s words, "An admirable man from every standpoint, the purest man, the most loyal friend that one can imagine," turned what otherwise would have been black days into one of the happiest periods in the picture dealer's long life.

The Kahnweilers were living at number 12 rue de la Marie, and every night Gris and his wife, Josette, joined them. Gris, who had an explosive temperament and was considered a Don Juan, loved to dance. He designed ballet sets for Diaghilev: Colombe, l'Education Manquée, and l'Amour Vainquer presented by Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, but not without arguments and complaints with the famed choreographer.

Gris gave grand public exhibitions and won dance competitions.

He bought dancing pamphlets as soon as they were published. He wanted to learn the newest steps, which he taught to every girl and young woman who came to the Kahnweilers. He acquired a phonograph with a great horn and made everyone march and dance — in the antechamber in winter and the garden in summer.

"I don't dance," confesses Kahnweiler, "but in those days I danced."

The miserable years in the Bateau-Lavoir undermined Gris's health: during his first major sickness, an attack of pleurisy, it had been necessary to suspend a sheet over his bed to keep the dirt off him. Recovery had been impossible in the Bateau-Lavoir. Finally he was taken to the Tenon Hospital, which he was unable to leave for eight months.

In 1923, Kahnweiler gave Gris an exhibition in his Galerie Simon in Paris, as did the Galerie Flechtheim in Berlin. The next year the latter gallery gave him a show in Dusseldorf.

More articulate than most painters, Gris delivered his culminating lecture, Des Possibilités de la Peinture/Possibilities of Painting, at the Sorbonne in 1924.

After 16 years of living in the Bateau-Lavoir on rue Ravignan in the filthiest lodgments conceivable, Gris moved, about 1922, to suburban Boulogne and a nice apartment.

For seven years after leaving the Tenon Hospital, Gris kept an enfeebled grip on life. He was forced to spend the winters in warm climes far from Paris. But his weakness drove him to more determined exertion — foxtrot, costume balls, and amorous conquest. Kahnweiler followed him into the Bailer, the Elysée-Montmartre, and the Moulin Rouge in order to get him out early and back to bed.

The affectionate devotion of Kahnweiler to Gris these years had been compared to the solicitude of Theo Van Gogh for his brother Vincent. In Puget-Théniers, where he had gone for the winter of 1927, Gris was stricken with an attack of uremia brought on by addiction to morphine, which he had been using to calm asthmatic convulsions. He struggled back to his suburban Paris apartment, pained, bitter, and abrasive of his friends who gathered around him.

When Gris died of renal failure at 40, this exuberant epoch in Kahnweiler's life came to a sudden end. Though not so popularly recognized as Braque or Picasso, says Albert L. Herbert, "Gris was a seminal force in modern art. His penchant for crisply defined forms and exquisite geometry placed him in the tradition of Ingres and Seurat and, with his highly personal sense of color, led him towards a structure of architectonic clarity whose impress was widely felt, even by Braque and Picasso."

To Kahnweiler, the loss of Gris's companionship was as great as the esthetic loss was to the rest of the world.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |