| Print | Back |  |

August 17, 2015 |

|

Moments in Art Auction Blockheadsby Lawrence Jeppson |

August 2, 1914. Rome. Hotel Eden. Every ten minutes Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, just turned 30, a prime military age, bolted down into the street to buy the latest editions of this or that newspaper and read of his gentle world being torn apart. The Guns of August.

War came, with all its consequences. An absolute pacifist, he was a man above national loyalties, whose only dedication was to art and his friends. The world gone mad, forcing men to take sides.

He would not return to Germany to fight the French. A German, he could not return to France unless perhaps to enlist.

He thought of offering his services as a medic, but his friends wrote discouraging the idea. Back in Paris, he learned from Eugène Reignier, who wrote him nearly every day, the gallery on rue Vignon had been padlocked: little did he realize that it would never be allowed to open again.

Kahnweiler's New York agent, Brenner of the Washington Square Gallery, pleaded with Kahnweiler to ship his stock to America, which could have been arranged, but Kahnweiler would not.

"No, no," he wrote Brenner, "that must not be done. The paintings must be left tranquilly where they are. Anyhow, nothing is going to happen to them."

He mailed his rent for the gallery regularly to Paris and hoped for the best.

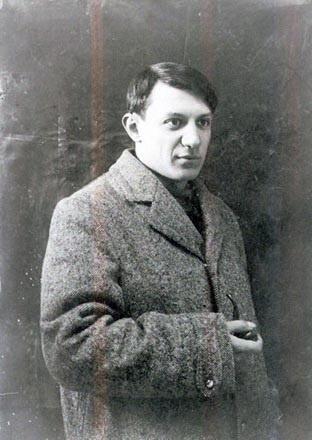

On that same day, August 2, Pablo Picasso escorted Braque and Derain to the rail station in Avignon. The artistic collaboration of Braque and Picasso was ended forever.

Juan Gris had gone to Collioure, a Mediterranean town near the Spanish border, for a modest vacation. He didn't have enough money to get back immediately to Paris. He couldn't reach Kahnweiler for help and found himself blocked into the Catalan port.

Matisse happened to be in Collioure and helped Gris sufficiently until Léonce Rosenberg took over the modest contract Kahnweiler had with the painter.

From Rome the Kahnweilers moved to Sienna, until persuaded by Hermann Rupf, a lifelong friend from Berlin, to come to Berne, where they would be safer, since Italy, everyone thought, was bound to enter the war. He promised them a furnished apartment, and they arrived on 15 December 1914.

Having no paintings to sell, Kahnweiler went into a protracted period of intellectual incubation during which he studied philosophy and wrote articles in German about Cubism, notably "Der Weg zum Kubismus" (The Rise to Cubism), which appeared in 1916 in serial form in Weissen Blätter, Zurich, and in 1920 in Delphin Verlag, Munich.

This was the first serious published treatment of Cubism, since Kahnweiler refused to accord Gleizes or Metzinger his imprimatur as bona fide Cubists, either in what they painted or wrote before the war.

He became a close friend of Robert Grimm, the prime mover of Swiss socialism, but did not meet the Bolshevik revolutionaries who frequented Grimm. He did not realize until after the fact that he had been studying shoulder to shoulder in the Berne library with Zinoviev, who later was instrumental in the ouster of Trotsky and was himself executed in the 1936 Soviet purge.

During the war, Dada became a social-wrecking art movement in Switzerland, and the Zurich police seemingly feared the Dadaists more than the Russians who lived and met across the street: Lenin, Radek, Zinoviev.

Picabia, Arp, Duchamp, Schwitters, and others contributed the plastic dimensions of Dada. Kahnweiler saw the outburst as nihilistic and destructive but likable. He went to Zurich only once or twice, but Dadaists Tzara and Arp occasionally visited him in Berne.

Vlaminck, a declared pacifist, was put to work in a French munitions factory. Braque was seriously wounded at Carency, and Léger was gassed at Verdun. Apollinaire was killed two days before the Armistice, and Kahnweiler's good friend Reignier died in the first wave of the slaughterous Spanish flu.

The Spanish aliens, Picasso and Gris, were left alone by the French government, but Picasso's great prewar outpouring had been fertilized by his associates: it had been, he said, the work of a team. Left isolated, his work changed considerably, reverting towards a classicist style, and while he did not abandon Cubism entirely, he worked after the war along various simultaneous but different routes.

The war caused a wide chasm of animosity to separate those who had gone valiantly to battle and been wounded (Braque, Villon, Léger, De La Fresnaye) and those who had been able to stay home (Picasso, Gris, Gleizes, Delaunay).

Writer Uhde had become something of a dealer for Cubists before the war, and like Kahnweiler he had been forced to abandon France. They were both Germans, a fact that was dramatized by their flight, and Cubism became tagged with the disastrous epithet "Bosch art."

Though mobilized, Léonce Rosenberg managed to continue to buy works of Picasso, Gris, Gleizes, Léger, Metzinger, Herbini, Hayden, Severini — and just about everyone else. He was, in the words of J. P. Crespelle (La Folle Epoque, 1968), "Little gifted for business and barely managed to keep his Galerie de l’Effort Moderne alive, so that he had to pass his two greatest stars, Picasso and Braque, on to his brother Paul. The latter, completely null in matters of art, had a genius for commerce and amassed an enormous fortune while his brother ruined himself discovering new artists."

Said Kahnweiler (in 1961), "There was one dealer — unfortunately the poor fellow made a mistake about what he should do, but who even so had a great deal of merit — Léonce Rosenberg, who really took over the painters I could no longer take care of, helping them and supporting them during the war."

Gris was helped some as well by Gertrude Stein.

Being German, Kahnweiler was unable to return to France, in spite of the 1918 Armistice, until after peace had been ratified, and so his exile in Berne stretched to five years.

He arrived in France on 22 February 1920,13 years to the day since he had first come to open a gallery. He found that the official responsible for his padlocked gallery had moved the paintings into a storage place on rue de Rome, where they had been damaged by humidity. But this was minor compared to new difficulties that were seemingly destined to crush him.

The gallery had been bolted and its paintings sequestered during hostilities because the owner was an enemy alien. The same political considerations and laws that enabled Kahnweiler to return to France also blindly confiscated all property belonging to former enemy aliens as part of the war reparations Germany was forced to pay France.

The French government — and virtually all Frenchmen — insisted on full and exception-less payment of these reparations. This meant the forced sale to the highest bidder of everything Kahnweiler and Udhe owned.

Kahnweiler's active support against such action came from his painters. They were hardly a political force.

Marshaling the patriotic evidence of their courage at the front, their wounds, and their decorations, Braque, Léger, and Derain undertook every move they could conceive to save the gallery. But Cubism had vested enemies: virtually all the galleries in Paris, "especially those located in the area of Rue La Boétie,” who detested Cubism esthetically; the non-Cubist artists, who in the painter community were in the majority; critics; and flag-waving politicians, most of whom didn't know two whiskers about art.

The antagonistic galleries were anxious to crush Cubism once and for all, and archrival Léonce Rosenberg joined in their cry for the liquidation of Kahnweiler's enterprise, but for the opposite reason.

Says Kahnweiler: "Léonce Rosenberg wanted the victory of Cubism but in his naïveté thought that the sales would be its triumph. It was an infantilism, and that corresponds to the lack of commercial sense which this poor man never ceased to show, since he ended up nearly ruined."

In five auction sales, one of them of the dealer's personal possessions, nearly 800 paintings and an uncounted number of drawings and other works by Picasso, Braque, Derain, Gris, and Léger were dumped on the market.

"No market in the world is capable of resisting such an avalanche."

Hardly a painting sold for more than 100 francs — at a time when the index strength of the franc was sliding from 180 (in 1919) to 20 (1926).

The last of the sales came in 1922; Kahnweiler attended none of them.

Rosenberg's envisioned triumph for Cubism turned out to be black catastrophe! Values dropped with each lot, and though prices had never been astronomical before the sales, they had reached a level of comfort for the artists. They now watched dumbfounded as the market worth of new works they were producing was destroyed with each thump of the auctioneer's gavel.

In their self-serving, stupid blindness the established Paris dealers bought none of the paintings, not even rich Paul Rosenberg, who had been buying Picassos for several years; nor did any of the world's museums have the foresight. For pennies they could have picked up fortunes.

The value of these paintings, if Kahnweiler, or anyone else, had them all today, boggles the imagination.

The auctioned paintings for the most part passed into the hands of poets, writers, and professional people. Kahnweiler was forbidden by law to buy back any of the paintings himself, and so he made arrangements for friends to bid on a few pieces he cherished, but he did not have resources to organize heavy buying to stock the new gallery he had opened in the spring of 1920 at 29 bis rue d'Astorg with the financial partnership of a broker from the Bourse, André Simon.

The new establishment carried the partner's name: Galerie Simon.

There would never again be a Galerie Kahnweiler.

In 1907, there had been but a sparse handful of galleries in Paris. In 1920, they began to blossom, one every corner like dandelions after a warm spring rain. "Along certain streets," Ambroise Vollard recounted, "every shop was a show window for a picture dealer. And that doesn't include traders who worked out of their domiciles."

One day Vollard encountered a woman in the street with several canvases under her arm. She complained that her husband would give her money for only one maid.

"Today," the woman said, "there is no way to earn money as good as being a picture dealer."

A friend, said Vollard, loaned the woman several thousand francs, and she purchased Cubist canvases at the Kahnweiler sale, which she began selling as prices started to improve. "Suddenly she had her second maid, then her auto."

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |