| Print | Back |  |

April 27, 2015 |

|

Moments in Art How Much is a Dead Zebra Worth?by Lawrence Jeppson |

Long ago I had a colorful associate whom I will identify simply as Ed. His last name in his paternal ethnicity was as common as Smith is in England.

He snared me in a challenge to appraise dead animals.

Ed owned a three-room antiques store in Bethesda, Maryland, only a block from the campus of the National Institutes of Health. He was a retired army colonel and had a doctorate — I think in economics — but had retired from late-career teaching to open his shop.

Maybe he did that to liquidate a ton of accumulated stuff. Some of his best stuff — a big collection of carved jades — never saw the shop but filled his apartment away from public view.

Ed had that infuriating gift (to me) of remembering most everything he read or saw about porcelains, jewelry, crafts — all those things that an antiques shop might offer. He had a wall of books that I envied. (My art library has become much bigger.)

When I tired of writing I’d get in the car and go hang out for a few hours with Ed.

Sometimes I’d be in his shop when an itinerant picker would come by to sell him some small treasure. He didn’t deal in big, clunky stuff or some of the almost junk you see on the History Channel show about two pickers from Iowa.

Ed had a Baron Munchausen need to embroider tales. His real life, however, was so chockablock with experiences he didn’t need to exaggerate.

Ed’s formidable speciality was Oriental antiques. As a young officer in the pre-WWII U.S. Army he had been posted to Nanking, China. After morning roll calls there wasn’t much for a young lieutenant to do. So every day he took off to the big museum, where, like an intern, he learned everything he could about Chinese art and objects.

This knowledge was expanded to include Japanese objects — he said he was a member of the Army detachment that handled the confiscation and disposal of the property of General Hideki Tojo, the Japanese premier executed for war crimes. During his Tokyo time Ed studied at the Ueno Museum.

During my hours at the shop I encountered a variety of interesting people. Some came to pick Ed’s brain, some to buy, and some to sell. From one of them Ed purchased a 500-year-old late Ming bowl. The surface was crazed and part of the bottom was encrusted with sand.

The inside of the grayish Caledon bowl had a subtle incised pattern. Owning nothing that old, I admired the bowl. Ed put a high price on it and placed it on a high shelf so that it wouldn’t sell and he could hold it for me. It sat there quietly for a couple of years.

When Ed closed his shop, turning the space over to the weirdest couple I ever met, he gave me a large office desk, three seven-foot merchandise storage armoires, and a nice Carvel Hall carving set. In exchange for work I had done, he traded me the Ming bowl.

Ed did a thriving appraisal business. Because his art knowledge was limited, whenever a job required evaluation of prints or paintings, Ed called me in. I did appraisals for Georgetown University, B’nai B’rith, the American ambassador to Belgium, and others, things ranging from a single item to a collection of 200 prints.

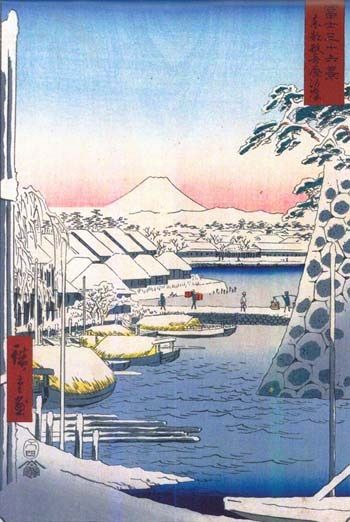

Ed acquired a collection of Japanese ukiyo-e prints by Hokusai, Hiroshige, and others. So many of these subjects have been remade and faked that they pose a serious problem of authenticity. I was thrown into the breach, maybe because I had written The Fabulous Frauds about art forgers.

I was way out of my depth. As in many museums, experts at the Freer Museum of Oriental art on the Washington Mall sometimes will authenticate art but will give no opinions on value. I telephoned the Freer and secured an appointment to see the appropriate curator — only I had to wait nine months to see him.

The curator said all but one of Ed’s prints were authentic. Then he brought out the original wood blocks used to print one of them.

Through those assignments and from just hanging out at the shop, I met a string of interesting people: the wife of the Dutch ambassador, a NIH doctor who repaired watches, Father Haller of Georgetown University, two friends from Holland who had gone to American med school together and then married doctors (ironic story here: Doctor One persuaded Doctor Two to take his place on a blind date; one week later Doctor Two married Doctor One’s blind date; Doctor One was not happy when he met the woman who had been his blind date.)

Besides the Dutch docs, three people stand out in my memory for the way they enriched my life.

One was Harry Wender. Harry was an old-time, downtown native Washington lawyer. You know, a local, not one of those imported into the city for political reasons. A contemporary painter of considerable fame painted a series of courtroom scenes. Harry purchased them and gave them to the United States Supreme Court and to one of the city’s law School.

Harry introduced me to other leaders of the Jewish community and taught me a great deal about how members aid each other and also contribute to the well-being of non-Jews.

The second was Ronald Senseman, a Fellow in the American Institute of Architects. He was the architect for the first Quality Inn Motorcourts, Choice Hotels, and Manor Care nursing homes, chains started by Stewart Bainum, a fellow Seventh-day Adventist. Ronald designed 2000 structures, including 50 churches and 150 schools.

He lived on a beautiful estate, which was maintained by Japanese gardener, and relaxed on a boat on the Chesapeake.

I offered him an opportunity to purchase the estate of John O’Shea, whom I wrote about in my column “O’Shea Can You See,” 20 July 2013. O’Shea painted the rugged seas of the Monterey, California, coast. These seascapes didn’t look like anything Senseman had seen on the East Coast. He passed.

The headquarters of the Seventh-day Adventists is in Takoma Park, Maryland. On several occasions Senseman invited me to accompany him to nearby Rotary Club meetings. As a Salt Lake Rotary might have a lot of LDS members, this Rotary Club was largely Adventist, with an appropriate menu.

When the Washington, D.C., Temple was open for pre-dedication visits, I was one of the brothers in charge of crowd control. I arranged for Senseman and the Seventh-day Adventist leadership to have tour tickets.

Our friendship gave me a deep appreciation of Adventists.

(I also made sure that Father Haller and his friends had tour tickets.)

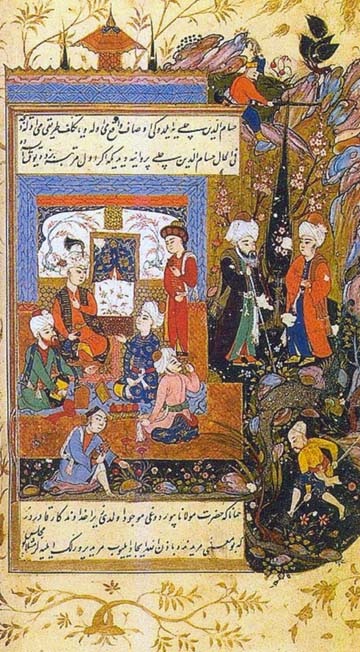

The third person was Dr. Reza Arasteh, a Jungian psychiatrist, an Iranian, a book author, and an admirer of the Persian poet Rumi (1207-1273). Reza had a son in California and a daughter back in Tehran coping with the new regime.

Reza often quoted from Rimi.

A consultant, Reza sometimes went to Japan to try to teach his group-minded clients how to be individually creative.

Reza often telephoned and we’d go off to lunch together, either to a Persian or a Chinese restaurant. He gave me books and taught me things I didn’t know. We began discussing doing a book together — he’d do most of the heavy writing. I’d be more like an editor.

Reza didn’t like medical doctors. I thought that was strange for someone of his training. He began complaining about severe abdominal pains. I convinced him to see my internist. I think in less than a year Reza was dead from colon cancer.

So there you have an interesting mixture of friends: a Jew, an Adventist, and a — well I don’t remember if Reza had an institutional religion. To these I should add Father Haller, a Jesuit. So many people can enrich our lives.

What does all of this have to do with dead zebras?

A big-game hunter in Florida decided to give his collection of mounted specimens to a natural history museum. How much were they worth?

Ed had no idea. Neither did I. But he dropped the problem in my lap.

As starting points, appraisals usually are based on some assessment of free market value. What have comparable things sold for in the past? What are the auction records? What have been the results of private sales, if they could be discovered? I once wrote for my own guidance a list of 54 factors affecting the value of a work of art.

There were no records, no market for trophies. Yipes!

The donor’s trophies went from simple skins (the least valuable) to mounted, record-making, largest-ever specimens (the most valuable).

I began my research huddled with managers at the National Zoo. I read zoo bulletins, international zoological newsletters, and all the books I could find recording the trophy sizes of every kind of animal. I also had to factor in what the donor had spent on safaris to get his trophies.

Although there was no discernable traffic at the time in mounted animals, there was an international traffic in live ones. Most of these — the legal ones at least — came from animal breeders or zoos that had animals to sell to other zoos.

A hunted and mounted specimen should be worth at least as much as a walking live one.

I developed the “Lawrence Jeppson Scale for Appraising Animal Trophies.”

I don’t remember the specifics of the scale, and my old records seem to have gone from file cabinet to sealed boxes. But... a simple skin would be worth only a fraction of the value of a live animal. A world-record trophy would be worth five times as much.

Ed’s eventual appraisal went on for pages, putting my work on his stationery.

I had become the world’s leading expert on appraising animal specimens. Nobody else was doing it. I had a corner on the market. I expected other big-game hunters would flock to my door.

None did.

I must have been beating a dead horse.

P.S./N.B. Please note that I no longer do appraisals, except in limited areas where I already have expertise.

| Copyright © 2025 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |