| Print | Back |  |

March 30, 2015 |

|

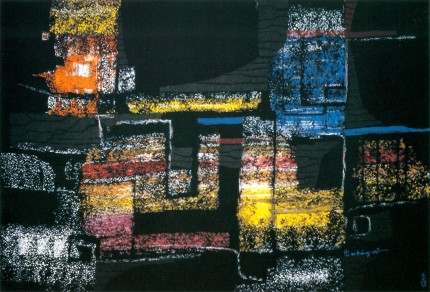

Moments in Art Mategot and the Hamburg Museumby Lawrence Jeppson |

This column first appeared May 28, 2012.

Since art is life, it has its full share of ironies. A notable trick of fate took 20 years to climax and involved a genius named Mathieu Matégot.

During the bleak days of World War II, the clandestine creation of handwoven tapestries in an obscure French village launched a renaissance of this once-noble art form. For centuries the village of Aubusson had been one of Europe's most important centers for handwoven tapestries, but as art its products had become repetitive and lamentable.

Located in unoccupied Vichy France, Aubusson became a gathering place for artists fleeing the Nazis. They began adapting their artistic visions to the disciplines of the loom and the skills of the weavers. They launched what became one of France's greatest 20th-century contributions to the world of art.

Matégot was not one of these artists.

Led by Jean Lurçat, all the Aubusson artists produced figurative tapestries. When Matégot took to tapestries soon after being liberated from a German prisoner-of-war camp, he broke the mold and introduced abstraction to the art. He became of one of the art's most influential leaders. He adapted age-old techniques and invented new ones. His discovery of winding two or more different colors on a bobbin is used by every tapestry artist in the world today.

In 1965, his magnificent tapestry Rouen was unveiled in the departmental capitol in Rouen, France. Covering 100 square yards of wall, it is the largest modern tapestry ever woven in one piece. He then produced four tapestries for the National Literary in Canberra, Australia. He was exhibited in hundreds of venues.

In 1963, the usually stuffy and conservative state museums in Germany arranged a one-man circulating collection. The show broke attendance records in Munich, Bremen, and Hamburg. In Hamburg the Germans made a particularly effusive fuss over him. He was honored by the mayor and all manner of festivities. To date, that was Matégot's biggest triumphs - and his biggest irony.

Matégot had been born of a wealthy land-owning family in Hungary. Like so many artists, he gravitated to Paris in the mid-thirties. He became a naturalized French citizen. Enlisted in the army, he was taken prisoner by the Germans. Although he escaped twice, he was recaptured. He was sent to a labor camp in Hamburg.

In bitter winter cold he was obliged to wash the outside of the windows of the Hamburg Museum. He was never permitted to enter it - until he came back as a conquering hero, thanks to his art, to be toasted and lionized by his erstwhile masters, who never were told of his forced-labor servitude with the museum that honored him.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |