| Print | Back |  |

March 09, 2015 |

|

Moments in Art Young Genius Captures History in Bronzeby Lawrence Jeppson |

In 1857, Southern generals in command of the U.S. military conspired to send an army headed by a Southern general to secure the West for the South in case of civil war. Needing to provide Congress and President Buchanan with an excuse, a situation was embroidered and stoked that the Mormon colony in Utah under Brigham Young was a threat to the nation.

The army would be led by Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston.

A year earlier, during the presidential campaign, the newly formed Republican Party carried a platform plank "to prohibit in the territories those twin relics of barbarism: polygamy and slavery." Playing into the Southern generals' hands, hotheads called for the extermination of polygamy and Mormon government of the Utah territory.

Subsequently, the conspiracy was discovered, the cabal defanged, and the West not seized for the Confederacy.

General Albert Sidney Johnston served in three different militaries: the Republic of Texas Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He fought in the Texas War of Independence, the Mexican-American War, the Utah War, and the American Civil War.

Until the emergence of Robert E. Lee, Johnston was considered the most able general of the Confederacy. He was killed fighting for the Confederacy in the Battle of Shiloh, 1862.

[Sometimes I have been challenged for my assertion about the Southern military conspiracy behind Johnston's army. It is something about which rank-and-file Mormons are not aware. They look at the Utah War as entirely an example of religious persecution. My source is the late Dr. Effie Mona Mack, head of the history department at the University of Nevada, Reno, in her book Mark Twain in Nevada.]

Both sides prepared for war. The Mormons began repairing and manufacturing firearms and beating scythes into bayonets. Mormon colonists from all the far places like Western Nevada were called back to bolster Utah. Utahns were preparing to carry a scorched earth tactic even into Salt Lake, if necessary.

The Mormons had their own militia, the Nauvoo Legion, a leftover from the persecutions in Illinois. Daniel H. Wells, a prominent Mormon leader and Lieutenant-General of the Nauvoo Legion (my wife's great-grandfather) instructed Major Joseph Taylor:

On ascertaining the locality or route of the troops, proceed at once to annoy them in every possible way. Use every exertion to stampede their animals and set fire to their trains. Burn the whole country before them and on their flanks. Keep them from sleeping, by night surprises; blockade the road by felling trees or destroying the river fords when you can. Watch for opportunities to set fire to the grass on their windward, so as, if possible, to envelop their trains. Leave no grass before them that can be burned. Keep your men concealed as much as possible, and guard against surprise.

Among the Mormon militia who took out against the American Army was Bill Keddington. Keddington was born in 1830 in Norwich, England. He and his parents were baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1848, a year after Brigham Young and the first Mormon pioneers, fleeing persecution, entered the desolate Salt Lake Valley.

Married at 18, Keddington and other converts sailed for America in 1852, landing in New Orleans. They traveled up the Mississippi to Keokuk, Iowa, where they joined a wagon train headed for Zion, arriving in 1853.

In 1914, Old Bill Keddington, 84, was the last survivor of the Utah War. Mormon sculptor Avard Fairbanks, only 16, wanted to do a bust of Keddington. While posing for young Avard, Keddington told about riding with Capt. Lott Smith and a small force into Wyoming, where they ambushed and burned crucial supply wagons.

Keddington and others rolled boulders down from cliffs to stampede Army animals. At nights the small band built a ring of campfires around the troops and paraded in the shadows from one to the other to make the Army believe they were surrounded by a superior force. In fact, the Mormons convinced the Army they were more than 50,000 strong.

The Army was forced to spend the winter at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, far from their objective. During this time, a long-time, non-Mormon, Eastern friend, Thomas Kane, who was well placed politically, negotiated a peaceful settlement that allowed Johnston's Army to march into Utah and set up camp, ending a war that had no human bloodshed.

As he posed for Young Avard Fairbanks, Old Bill Keddington regaled him with the stories of the Utah War. But why would the wizened warrior agree to let a kid sculpt him? It could have been an old man's vanity — or that no one else had ever thought about it. However, Avard already had a genius reputation, not only in Utah but in New York City.

Born in Provo, Utah, Fairbanks was the tenth son of John B. Fairbanks (1855-1940), an important pioneer artist, from whom Avard inherited artistic gifts and encouragement. Less well known is the fact that Avard’s mother, Lilly, who died from a fall when Avard was one, had a flair for modeling three-dimensional articles.

She would combine sand, earth, pebbles, brush, grass, and twigs, and using small mirrors to represent lakes and brooks would model miniature landscapes that won a number of diplomas and other awards at the state fair. She designed wreaths from seeds and flowers.

When she finished her weekly churning, she would sculpt the butter into birds and animals. One readily foresees the boy in the Bronx Zoo, as we shall see.

After his mother died, Avard and his father moved to Salt Lake City, where an older sister, Nettie, helped raise him. In the third grade he evidenced an intense interest in drawing. His older (by 19 years) brother Leo J. Fairbanks (1878-1946) was art supervisor in the county schools, and Avard’s association with his brother already may have been stimulating the boy. Certainly it did a little later.

By the time Avard reached the sixth grade he was modeling in clay. Leo took private students, and one summer day Avard said to his brother that he could do better than a particular student in drawing and modeling. Leo’s reply was, “All right, go ahead, let’s see if you can.”

Avard’s sketches were not better, so he turned to modeling. He took a pet rabbit out of its cage and modeled it at one-quarter scale. It was a piece of good work, but the casting was unsuccessful. He started over, modeling the rabbit at one-half scale. The casting was successful and the bronze bunny was publicly exhibited.

In June, 1909, John B. took twelve-year-old Avard with him to New York, where the father was making copies of famous paintings in the Metropolitan Museum. Not wanting the boy to run around loose in New York, John B. asked the Met to allow Avard copying privileges.

Despite the answer that, “We can’t have children running around here,” the request was granted, and soon Avard was copying Lion and Serpent by Parisian Antoine Louis Barye (1796-1875), the most formidable sculptor of animals of the 19th century. A lad of twelve working in the museum soon attracted crowds.

The museum director apologized to John B. for being incredulous when the copying request was made. A reporter for The New York Herald eventually stumbled onto the scene and returned with a photographer. As soon as the paper began telling its readers about the boy, the rest of the press followed.

Although Avard was only twelve years old when he began modeling animals from life in the Bronx Zoo, his buffalo and other animals attracted the serious attention of Sculptor James Earle Frazier (1876-1935), who was making designs for the Buffalo nickel using the same animal as model; Sculptor Alexander Phimister Proctor (1862-1950), who was making the four big Que Street Bridge Bison that are the gateway between Washington and Georgetown; and Painter Charles R. Knight (1874-1953), “who refined his skills sketching animals at the Zoo in Central Park and was the first to apply the universal principles of animal design to the reconstruction of ancient life.” (Designing Dinosaurs, Bruce Museum).

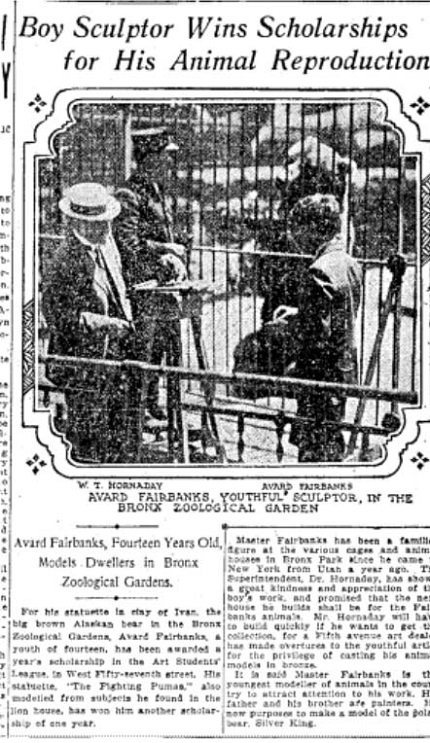

These men, and Dr. W. T. Hornaday, curator and Zoo superintendent, were so impressed by young Avard’s talent that they procured two successive scholarships for him to the Art Student's League on West 57th Street, Manhattan.

Dr. Hornaday was a noted naturalist and animal writer of world-wide fame. The New York papers described him as the “the young Fairbanks’s steadfast patron, showing him every kindness and appreciation of his work, and says the next house he builds will be for the Fairbanks animal collection.” (Quoted by The Herald-Republican, July 2, 1911.)

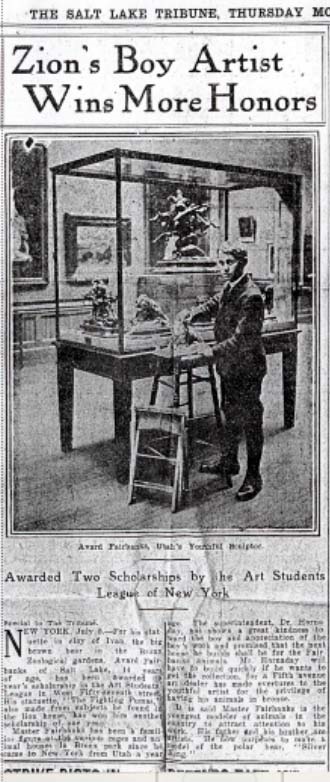

Four days later The Salt Lake Tribune picked up the story and added a picture of the young sculptor with one of his animals standing in front of an exhibition showcase filled with other small bronzes. It warned that if Dr. Hornaday wanted Avard’s animals he had better move quickly because a Fifth Avenue art dealer had made overtures to cast the animals in bronze.

The Tribune mentions Avard’s having completed a model of a polar bear, Silver King, in addition to The Fighting Puma and Ivan, the Alaskan bear.

Another newspaper clipping, with the headline “Boy Sculptor Wins Scholarships for His Animal Reproductions,” shows Avard posing with Dr. Hornaday and a zoo guard in front of Ivan the Bear’s cage. Ivan is on his hind legs looking at them — and perhaps also at the model of Ivan, which sits on a high, narrow stand between Avard and the other men. It’s a delightful old photo.

Art Historian William Bridges in Gathering of Animals, Harper and Row, 1966, quotes the experience of Paul Branson, an illustrator who recalled his time at the Zoo:

Mr. Frederick G. R. Roth had a locker in the room, (designed to draw and model animals at the opposite end of the building) but he always did his work out in the main Lion House (where the light was on the animal). Mr. Roth was (in my opinion) the finest animal sculptor America has produced. The only other artist in constant attendance whom I can recall at the moment was a lad in knee breeches names Alvord [sic] Fairbanks. He was always quietly drawing somewhere around the Park. I tried to make his acquaintance, but he was a “loner” and shied away from all attempts to become acquainted (Fairbanks was a fourteen-year-old prodigy from Utah who won a scholarship from the Art Students’ League for his model of Sultan, the lion.)

Avard’s zoo statuary (which included a notable Alaskan big brown bear named Ivan and a Fighting Puma) got him written up and pictured in New York and Utah newspapers, early publicity that would follow him his entire career. (He complained in a letter home, 7 March 1911, “When they came to interview me they never took down one word and when they wrote it they got it all mixed up.” He was not the first or last artist to vent that complaint, but he was certainly among the youngest.

The papers were probably right when they observed, “It is said he is the youngest modeler of animals in the country to attract attention to his work.”) More stories and pictures appeared in July newspapers in New York and Utah, and probably elsewhere.

The boy heard rumors through the press that Big Brother Leo was going to take him to Europe to study, but that did not happen that year or the next. Avard did write Leo that he would introduce him to Gutzon Borglum (1867-1941), Proctor, Frazer and others if he would visit him in New York.

Back West, young Avard’s sculpture carried off virtually all the prizes at the Utah State Fair.

The next year (Avard was 13), one of his pumas was accepted in the exhibition of the National Academy of Design, and he was accepted again the next year with a piece referred to at the time as The Bull but which is actually Buffalo Charging, which was exhibited in Buffalo. The quality of The Bull/Charging Buffalo gave his career a substantial boost.

The time young Avard spent at the Bronx Zoo modeling his animals was part of a demanding routine. He did not want to fall behind in his class studies back in Salt Lake. He and his father were living in New Jersey and commuting. Avard would leave home at 8:00, study while riding on the train, spend the day at either the Met or the Zoo, study nights at the Art League, and get home around midnight.

A piece that won him wide recognition was a bas relief showing Hiawatha learning “from every bird its language,” based on the Longfellow poem. Published by a New York company, “this fine bit of work is finding its way to all parts of the country.” (Young Woman’s Journal)

The same year that Avard was sculpting Old Bill Keddington, a biography of young Avard appeared in Young Woman’s Journal:

In years to come when the question shall be asked, “What men and women of genius have been given to the world by Utah and ‘Mormonism?’ The list submitted in answer will contain the name of Avard Fairbanks, Utah’s boy-sculptor. This prediction is based on the work that he has already accomplished, the spirit he possesses of desire and determination to excel, and the helpful encouragement of his father and brother — both artists — who refuse to permit the lad’s native ability to remain undeveloped. If Avard does not attain to greatness it will be because of circumstances that are now wholly unforeseen.

After disappointments in not being able to go sooner, Avard and his father started out for Europe in 1913. They stopped in Chicago as guests of a number of leading artists and the Chicago Art Institute. Their departure from New York was delayed when young Avard was commissioned by a wealthy woman to sculpt portraits of her three children.

Finally in February, 1914 (the date given by the Young Woman’s Journal) — he was 16 — Avard went off to Paris to study in the Académie de la Grande Chaumière et Colarossi, in the Ecole Moderne with Jean-Antoine Injalbert (1845-1933), and at the Ecole Nationale des Beaux Arts.

Continuing to do a great deal of work with animal forms, Avard became, in 1914, the youngest artist ever admitted to the famous French Salon.

The dates for his study in Paris are interesting, since they coincide with the outbreak of World War I. The conflict forced father and son to return home.

So, in 1914, when Old Bill Keddington posed for the Young Avard Fairbanks, the boy was already famous.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |