| Print | Back |  |

January 5, 2015 |

|

Moments in Art Miraculous Toothacheby Lawrence Jeppson |

As Nazi hordes swept in all four directions to gobble up Europe, any work of art that could be transported was viewed as legal plunder. After all, Hitler had signed a decree obliterating previous ownerships, particularly if the owners were Jews.

Even though many masterpieces from the Louvre and other museums had been successfully hidden from the marauders, France was still rich with plunderable art. Among the occupiers of Paris was an SS officer who had been trained at Harvard. He was an intellectual, and his interest was in French sculpture of previous centuries.

The officer was writing a scholarly catalog of his findings. Although his research was far from complete, he gave a two-volume report to Herman Goring, the most rapacious art thief among a legion of Swastika-wearing art thieves.

Goring was so impressed that he promoted the SS officer, who became a proficient looter. He was given the title of Director, German Fine Arts Institute, Paris. Among his thefts was the Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidered tapestry about 20 inches high but 230 feet long, created in England about 1070, and depicting William the Conqueror’s taking of Britain.

Besides its irreplaceable artistic value, the tapestry’s story must have been music to Nazi ears.

In the trial of major German War Criminals in Nuremberg, Germany in March, 1946, Justice Jackson, from the U.S. Supreme Court, asked Defendant Herman Goring if the SS officer had been involved in the multiple thefts from Jewish collectors. Goring replied, “I do not believe he had anything to do” with confiscated Jewish art. “He was in charge with a different field of art.”

As I wrote in December, as Allied forces moved westward in the Liberation, an overworked small group of soldiers of the Monuments, Fine Arts, & Archives squad moved with them, cataloguing what had survived, seeking stolen art, and dissuading leaders from bivouacking troops in castles and other artistic venues. It was a huge job for so few men.

Attached to Patton’s Third Army were Captain Robert Posey and Private First Class Lincoln Kirstein, the lowest rank of any of the Monuments Men.

An architect, Posey began his military service in 1942 in the Corps of Engineers, building airstrips in Churchill near Hudson Bay in Canada. He was part of the group who planned the MFAA in England before the Normandy landings. After the war he would have a distinguished career in Alabama, where he became one of the state’s favorite sons.

Assigned as Posey’s assistant, Kirstein, was a writer and art collector. Three years younger than Posey, he was born into a well-to-do Rochester family. As a Harvard student he founded the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art and a short-lived literary magazine, The Hound and the Horn.

In 1933, he brought the Russian choreographer George Balanchine to America and jointly founded the School of American Ballet. After the war he became openly identified with a gay lifestyle, which, if known earlier, would have prevented his military service.

Initially assigned to Nancy, France, Posey and Kirstein followed Patton’s army into Trier (Treves in French and English), on the banks of the Moselle River, Germany, a city of 100,000 near the Luxembourg border. According to legend, Triers was founded by an Assyrian prince 1300 years before Rome, which would make it one of Germany’s oldest cities.

Among Trier’s religious edifices were the Constantine Basilica, which includes a 220-foot throne room used by Emperor Constantine, and Trier Cathedral. The city was marked by Roman bridges and monuments of many kinds which required assessment by the Monuments Men.

It was also the birthplace of Karl Marx.

The men discovered the advantage of persuading native citizens to help catalog and assess surviving work and search for things stolen.

Posey developed an excruciating toothache.

There was no army dentist within a hundred kilometers. Desperately in pain, he decided to seek a German dentist. In their meeting the dentist learned of Posey’s mission. He said Posey should meet his son-in-law, who was an art scholar and would enjoy talking with the American.

Well, where did this art lover live? Oh, about 20 miles outside of town. That was off-putting, not like a convenient conversation with somebody across the street.

Unlike most of the Monuments Men at this early stage in the war, Posey and Kirstein had a staff car. The son-in-law and his family lived in a secluded house in the mountains. If the dentist did not come as guide, the men would never find it.

Much to Posey’s discomfort, the dentist insisted on making time-killing stops on the way. There were friends he had not been able to see for a long time. Posey became increasingly uneasy: a couple of American soldiers alone in enemy country.

They were surprised to find a house full of scholarly books and walls replete with photographs and art reproductions, primarily French.

The German admitted he had been living in Paris until just the day before liberating troops moved in. Abridged, the conversation went something like this:

“I have information which will help you very much. I propose an exchange. I will give you the information, but you must give me and my family asylum in America.”

“I cannot do that. I’ll do what I can, but I have no authority.”

Finally, the son-in-law was persuaded to reveal what he knew and take his chances later with the Americans.

As Robert Edsel reports, “They learned more in 20 minutes than they had in the last twenty weeks.” [The Monuments Men, p. 268]

Hitler’s greatest horde of looted art was hidden deep in salt mines in Austria. This was the first time anyone on the Allied side had heard anything about the mines. Soon, a race developed: the Americans had to get there before Russian troops occupied that part of Austria.

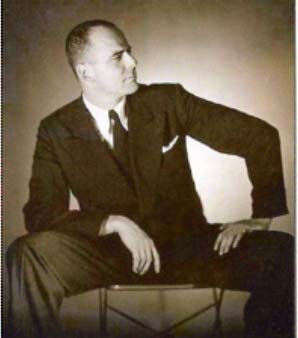

The scholar was Hermann Bunjes, educated in Harvard, Paris, and Marburg, an expert on medieval French sculpture. He was an early member of the Nazi party and ran the Berlin State Museums between 1933 and his posting to Paris. He was that SS officer in Paris who had caught the eye of Goring and became involved in voluminous art theft and shipment of trainloads of it back to secret Third Reich repositories.

Hiding in his mountain house, Bunjes had three fears: the Nazis (he was a deserter); German civilians (many of them hated the SS); and the Americans. He wanted nothing more, he said, than be able to go back to Paris and complete his studies.

No SS officer would ever be admitted to the United States. And Bunjes was no low-level officer. How deep would the war trials go?

Facing retribution, Bunjes killed his wife and child and then took his own life.

Posey’s excruciating toothache led to the war’s biggest recovery of stolen art.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |