| Print | Back |  |

October 27, 2014 |

|

Moments in Art William's Coupby Lawrence Jeppson |

Last week I wrote that for a century Thomas Agnews’ gallery dominated the British market for art prints. I can’t skip telling several compelling stories about how Agnews’ accomplished this, stories that will take us into the heart of the Crimean War.

After Vittorio Zanetti had gone off to retirement in Italy and his son had disappeared from the business, Thomas took his two sons into the business. The Manchester firm thereafter was known as Thos. Agnew & Sons. Eventually it would pull out of Manchester and Liverpool and move to London.

The print business changed in a way that gladdened the days of tens of thousands of Englishmen. Political depictions were overtaken by engravings of paintings by popular contemporary landscapists.

Thomas commissioned J.B. Pyne to paint the nearby Lake District, and the views were among the artist’s first landscapes. Their publication in 1851 as a series of colored lithographs was such an instantaneous success that Agnew sent Pyne off to Italy to do a continental sequel.

The paintings Pyne brought back were good, but engravings were never produced, and for unexplained reasons after that Agnew concentrated on black and white pictures.

No better example of Thomas’s print acumen can be shown than his transactions with four large paintings done by J.R. Herbert on the history of the English Church: The Acquittal of the Seven Bishops, The Death of John Wesley, and two others.

He laid out a prodigious £5,000 to acquire the four originals and to whip up public interest by exhibiting them in the Royal Academy in London and in many of the big provincial cities such as Liverpool and Manchester. Then he issued artist's proofs (at the highest price because they were signed by Herbert), proofs before letters, lettered proofs, and prints.

To protect himself from piracy and cutthroat competition, Thomas organized the Printsellers’ Association. Members registered and authenticated for each other all their editions. Thomas became its president, and so dominant was Agnews’ publishing activity for three generations that his son, William, and then his grandson, Morland, followed him into that chair. The date of organization was 1847.

Operating from Manchester, the firm had not as yet captured as large a share of the London market as London publishers; however the publication in 1855 of Clarkson Stanfield's H. M. S. Victory Bearing the Body off Nelson, Towed into Gibraltar after the Battle of Trafalgar became so popular that parity with London editors was finally achieved.

Then Thomas published prints from two Crimean War paintings by Thomas Jones Barker: The Allied Generals before Sebastopol and General Williams and Staff Leaving Kars with such enormous success (1000 artist's proofs and 2,000 proofs before letters of each) that the firm took in over £10,000 for each plate just for the artist's proofs.

Prints of Jerry Barrett's Florence Nightingale at Scutari and Queen Victoria and Prince Albert Meeting Wounded Soldiers were comparably received. So successful were these six prints that the accounts book of Messrs. Chance, Agnews’ supplier of glass for frames, filled page after page.

The Crimean war afforded son William Agnew his first extraordinary coup, something akin to American publisher James Gordon Bennett's later dispatching of Stanley to find Livingston. It was a portent of what he would do when he finally took over management from his father.

War dispatches from The Times correspondent William Howard Russell were so vivid in describing the initial mismanagement of the war and appalling conditions of life and death among the troops that they were traumatically disbelieved at home. With government cachet, William dispatched Roger Fenton to the Crimea as one of the world's first war photographers.

Before setting out, Fenton adapted a wine merchant's wagon for living, cooking, sleeping, and photo processing. With a handyman cook and a former corporal in the Light Dragoons, as a driver, he set out from England in February, 1855.

The equipment filled 36 large cases. It included five cameras with various lenses, some seven hundred glass plates, chests of chemicals, gutta percha baths, printing frames, cisterns for distilled and ordinary water, carpenter's tools, tent, stove, harness, and supplies of tinned foods. At Gibralter Fenton bought four horses to draw the van.

Colnaghi's (a rival London art dealer) had dispatched William Simpson to make drawings of the war, but Fenton had entree that his rival did not: letters of introduction from Prince Albert to the British ambassador and English and French general staffs.

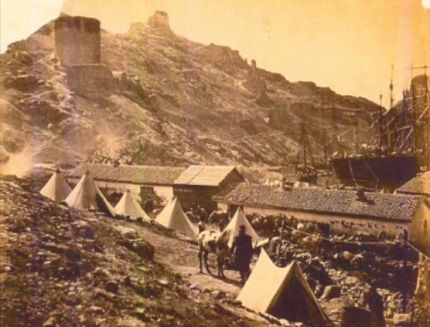

The letters were of no assistance in getting Fenton's stuff off the vessel at Balaklava. He wrote back to William from shipboard, "The whole place is a pigsty. At present 80 sheep are slaughtered every day in the vessels in harbour alone, and the entrails thrown into the water alongside. Sanitary conditions landside were appalling."

After four days of waiting for official help, he despaired and made his own arrangements, "a glorious work of private enterprise," he wrote. Once on land he met cordiality from the generals and could go wherever he wanted with freedom.

To repel the overbearing Crimean heat Fenton had painted the photo lab white. Enemy batteries mistook it for an ammunition wagon, and Fenton found himself a constant target. It was hit only once.

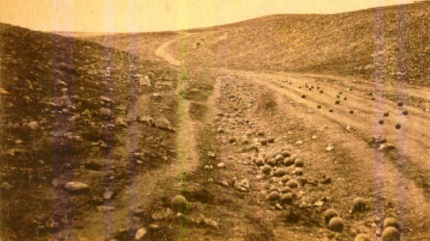

Using two borrowed mules, as Fenton wrote, "[I] took my carriage down a ravine known as the Shadow of Death (not the scene of the Charge of the Light Brigade) from the quantity of Russian balls which have fallen in it. I had been down to the caves two days before to choose the views ... I took the van down nearly as far as I intended to go and then went forward to find our chosen spot.

I had scarcely started when a dash of dust behind the battery before us showed that something was on the way to us. We could not see it but another flood of earth nearer showed that it was coming straight, and in a moment we saw it bounding up towards us.

It turned off when near, and where it went I did not see, as a shell came over about the same spot, knocked its fuse out and joined the mass of its brethren without bursting. It was plain that the line of fire was upon the very spot I had chosen, so very reluctantly I put up with another view of the valley 100 yards short of the best point.

I brought the van down and fixed the camera, and while leveling it another ball came in a more slanting direction, bounded on to the hill on our left about 50 yards from us and came down right to us, stopping at our feet. I picked it up and put it in the van; I hope to make you a present of it.

After this no more came near, though plenty passed on each side. We were there an hour and a half and got two good pictures."

Heat was as great a villain as enemy balls. The wet collodian Fenton had spread evenly over his large glass plates began to dry as soon as it touched the surface, and since a plate had to be moist when it was developed after exposure, he probably was unable to shoot more than 100 yards from his van.

"When my van door is closed before the plate is prepared, perspiration is running down my face and dripping like tears. The developing water is so hot I can hardly bear my hands in it." Glare from the sky and the green less battleground forced him to quit photographing after 10 in the morning.

After the massive attack on Sebastopal failed in June, Fenton, suffering from cholera, sold van and horses and sailed for home. He was summoned by Victoria and Albert to recount his adventures, but he was so weak that they let him do so while lying on a couch.

When the royal couple went to Paris in August they took 20 Fenton photographs to show Napoleon III. The next month Fenton and William Agnew took the whole collection — 360 photographs — to the Palace of St. Cloud.

The French empress was ill and not present, but Napoleon spent an hour and a half examining the pictures. Whenever he found one of special interest he took it to the next room to show the empress.

The emperor seemed surprised that "something which could only have been undertaken by the Imperial Government in France should be the speculation of a private firm in England."

Agnews’ put 312 of the photos on exhibit in Pall Mall at the Water Colour Society. "An exhibition of deeper interest was never opened to the public. It is a pictorial and running commentary of the graphic narrative of The Times' special correspondent. The stern reality stands revealed to the spectator.

Camp life with all its hardships is realized as if one stood face to face with it; and after viewing with deep emotion the silent gloom that overshadows “The Valley of the Shadow of Death,” the eye rests with deeper feelings on the tombs of Cathcart's Hill.

Various portfolios were published by the firm: "Incidents of Camp Life,” “Historical Portrait Gallery,” “Views of Camp,” “The Photographic Panorama of the Plateau of Sebastopol,” “The Photographic Panorama of the Plains of Babylon and the Valley of Inkerman.”

A general selection of 160 prints sold for 60 guineas and single prints for 10/6 to 1 guinea.

With peace in 1856, interest in the photographs diminished. They had sold well but not so well as Agnews' best art prints. More significant than their commercial success were the footsteps in photo journalism traced by Roger Fenton, a stimulus to Matthew Brady and all other cameramen who thereafter followed troops to battle.

| Copyright © 2025 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |