| Print | Back |  |

October 13, 2014 |

|

Moments in Art From Z to Aby Lawrence Jeppson |

Urbanized England after Waterloo became a pervasive ugly slum.

In 1815, rural England — soon to be overrun in the north by sprawling jerry built factory blights — boasted an unspoiled beauty worthy of the finest landscapist (John Constable). Her towns were solidly handsome or at least picturesque.

But the 20 years of brutal conflict with Revolutionary and then Napoleonic France came at the worst possible time in England's abrupt Industrial Revolution. In the rush of social transformations the war served the worst conceivable motivation and environment.

What had been beautiful turned ugly, and ugliness was rendered acceptable.

It was a time propitious neither for artists nor for art dealers. And yet there was a redeeming feature: for a hundred years England would be spared major war, while five generations compounded and then exorcized its grandiose problems.

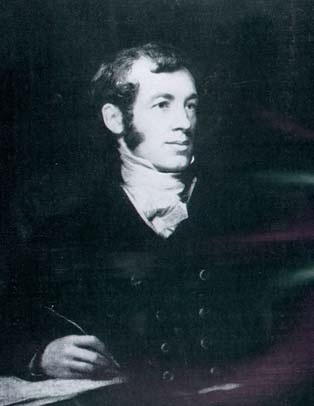

Waterloo and England's first extremely controversial Corn Law to help farmers was still five years in the future when Thomas Agnew, 15, took apprenticeship in Manchester with Vittore Zanetti.

(Genealogical research might reveal that this Zanetti was a descendant of the Zanetti who profited so regally from the downfall of collector Evrard Jabach, 1618-1695, whom I wrote about last year, "Moments," 15 July 2013.)

Zanetti was an Italian born dealer in pigments, pier glasses, primed canvas, and picture frames. Tom had been born (16 Dec. 1794) eight months after his parents' marriage. His father was already dead. The boy and his mother lived in Liverpool.

When he was 11, she married a schoolmaster named Walter, who "always behaved to me with the kindness of a father to a son," even though the new couple produced six offspring of their own.

Thomas found a friend in John Gibson, who was four years older and destined to become a sculptor. Gibson haunted the print shops of Liverpool. Too poor to purchase what amused him, he memorized figures he saw and drew them when he returned home. In all likelihood, Thomas explored with him: such was his introduction to art, setting him up for Zanetti in Manchester.

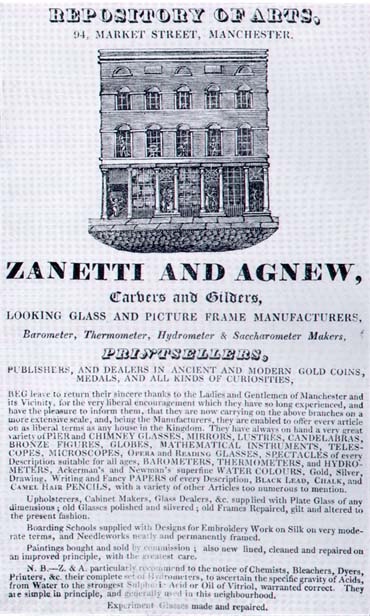

In all of northern England there were only two art dealers of any consequence: Burland in Liverpool and Zanetti. “Art dealer” was a term as broad as the white cliffs of Dover.

Zanetti manufactured and sold barometers, thermometers, hydrometers, and saccharometers. He was stocked with chimney glasses, mirrors, lustres, candelabras, bronze figures, globes, mathematical instruments, telescopes, and microscopes. His artists' stock included Ackerman's and Newman's superfine water colours, fancy papers of every description, black lead, chalk, camel hair pencils, and (his own words) "a variety of other objects too numerous to mention."

Not to be caught idle, the firm did upholstery, made cabinets, polished and silvered mirrors, and repaired, regilded, and remodeled picture frames. Zanetti was also a printseller, publisher (the earliest known print was issued in 1813), and dealer in ancient and modern gold coins, medals, and all kinds of curiosities. Oh yes, an old handbill added near the bottom:

“Paintings bought and sold by commission.”

Zanetti was staging annual exhibitions of what he said were old masters.

In an 1817 letter, Thomas wrote: "I now have a very good salary and have at a future period the opportunity of entering into the concern as he (Zanetti) wishes to withdraw, being advanced in years. I have the principal management of the business and have no doubt of ultimately succeeding if I am assiduous and attentive."

Zanetti already had a partner, an unfortunate Mr. Bolongaro, who had overbought in hydrometers and barometers.

Six months after Thomas's prophetic letter, Sept. 30, 1817, Zanetti advised through the Manchester Mercury that he had "taken into partnership Mr. Thomas Agnew, whose ability, assiduity, and attention to the various branches of the business connected with the Establishment will at all times ensure a ready and punctual attention to the Orders and Favors of their Friends, of whom Vittore Zanetti respectfully solicits a continuance."

One of the most formidable dynasties in the history of art dealing was born.

The firm, as Thomas Agnew & Sons, would remain in Agnew family hands for nearly 200 years, until it was sold in 2013. Agnew family members retain an advisory interest.

The partnership, originally prescribed for one year and later prolonged to five, did not start equally. Zanetti put in £1,000, Thomas £3,000. Neither could buy over £10 in a month without the other's consent, although if the old Italian were absent, the 22 year old Englishman could run up debts of ten times this in any month. Their weekly draws were equal: £1.11.6d.

A new agreement in 1822 added seven years to the partnership. By 1824, Zanetti and Agnew's stock was carried on the books for £7,000, each partner was drawing £150.10s per year, and the remaining profit was a substantial £2,000.

A portion of that profit came from a sideline remarkable for art dealers: the company was renowned as a seller of sweepstakes tickets.

| Copyright © 2025 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |