| Print | Back |  |

September 8, 2014 |

|

Moments in Art Multiplications, Sort Ofby Lawrence Jeppson |

The world is afloat with tidal waves of mechanically reproduced images. They are made like newspapers are made, with mechanically created plates printed in great numbers. Sometimes, if the images are artistic creations, the quantity may be limited; the impressions are numbered and, best cases, signed, titled, and numbered by the artist.

Hundreds of millions of illustrations hang on walls on every structure in the world. Many are calendars or pages torn from calendars, cheap images bought from hobby stores, or prints from the internet. They give pleasure, reinforce spirits, reflect personalities, or simply simplify the boredom of bare-space walls.

Mechanically engineered images printed in great numbers have no artistic or market value. With the exception of one good calendar and one framed image, I will not allow these artistic masquerades on our walls. Fortunately, we have too much good stuff to hang.

The one framed mechanical image is of an artist’s painting of the Enola Gay in flight, returning from its mission over Hiroshima. It is not even numbered, but it is signed by the artist and the five members of the mission who were still alive when it was printed: the pilot, the navigator, the bombardier, the radio operator, and the weapons officer who was responsible for arming the bomb in flight, Lt. Morris R. Jeppson, my brother.

There are many forms of legitimate “multiple-originals.” These are limited-edition lithographs, serigraphs, etchings, and engravings whose plates are made by the artist or by the artist in collaboration with a master printer.

I published five images by Mathieu Matégot. They were produced in the workshop of silkscreen printer Lou Stovall in Washington, D.C., with Lou, Matégot, and me working together to get the results the artist wanted.

Lou’s silkscreen inks had to be hand mixed to get Mathieu’s exact color. Each color was laid down by a separate screen. Like the inks most silkscreen printers use, Lou’s were opaque. Should any ink overlap another, the under ink would be blotted out. Lou, however, was so skilled that colors would abut, not overlap.

Later I published five silkscreen prints based on watercolors by my daughter Anne Bradham. The printer was the late Rob Carawan in Spring City, Utah. Rob was a genius in using transparent inks. One color laid over another would produce a third color. Rob was so good that he could produce editions that were difficult to distinguish from the original watercolors.

Historically, the French and the Japanese have been notable printmakers. Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939) was a powerful Paris art dealer who represented the cream of French artists of the early 20th Century. He was also the most important publisher of etchings and lithographs.

His editions, including fabulous series by Rouault and Picasso, often were printed by the atelier of Fernand Mourlot. Over a 50-year period, Mourlot printed 407 Picasso images.

I have silkscreen prints by Nat Leeb printed in the 1960s by the Mourlot atelier that required 56 separate screens.

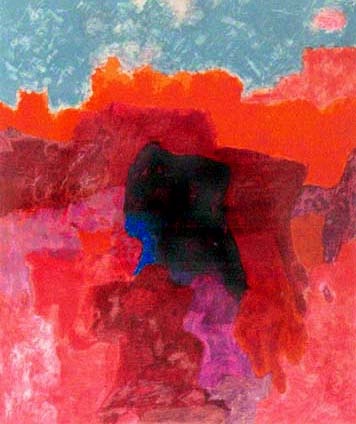

My favorite modern printmaker was Edouard Jaquenoud. He was born in 1926 (my age) in Neuchatel, Switzerland. Like many European artists, he wanted to study in France, but he had to wait until after the Liberation, 1946, to make his first pilgrimage to Paris. The next year he went to Spain to continue his work in ceramics and painting.

His first show was held back in home town Neuchâtel in 1951. The city gave him a grant that allowed him to return to Paris to study and work. There he had a succession of exhibitions. He also was shown in Caracas, Munich, Hamburg, Bayreuth, and Geneva.

He settled on a French farm, where he proved his genius in creating lithographic prints. Unlike the Vollard/Mourlot editions, Jacquenoud restricted the tirage of any edition to a limit of 10, usually fewer.

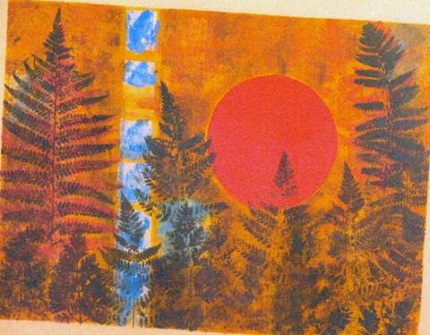

When he made his nature prints he would use a real leaf or other greenery, ink it, and print. The leaf would be destroyed in the process, and although a stone might be used for other elements in the print, the print was limited to a single piece. This made them true monotypes.

To print his own work, Jaquenoud acquired the litho press that had belonged to Ambroise Vollard. Besides its aged technical excellence, the press inspired him to do great work with it. He could handle the heavy work of manual printing because he had huge arms like a National Football League lineman, which went well with his thick, black beard.

I met Edouard through my artist friend and tapestry cartonnier Marc Petit in Paris. Among my large acquaintanceship with French artists, he immediately became one of my favorite people.

In the 1960s, I gave Jaquenoud his first exposure in the United States, with exhibitions in a dozen cities. He already had been acquired by actors Tyrone Power and Charles Laughton and artist Mark Tobey.

Jaquenoud’s tragedy is that he was passionately in love with his wife and was dependent upon her. When she died too young from cancer, it was more than he could bear. Distraught, he hanged himself, ending an extraordinary career.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |