| Print | Back |  |

September 1, 2014 |

|

Moments in Art Scream Heard Round the Worldby Lawrence Jeppson |

When there was a lot of stuff loosely guarded, and Reidae Revold was the trusted guard, the temptation to steal was overwhelming.

My artist daughter Anne and I found ourselves in Oslo, Norway during our two-month Eurails-pass art wandering that took us from Madrid and Rome on the south to Narvik, Norway, north of the Arctic Circle. In Oslo we marveled at the dramatic city hall, an exhibition of resurrected Viking ships, and the Kon Tiki raft that carried Thor Heyerdahl across the Pacific. We had not yet visited the Munch Museum.

On the map the museum didn’t look that far away from central Oslo, where we were staying. We decided to walk. It was a lot longer away than what we thought.

A couple of decades later my wife and I were in Oslo. We and another couple decided to take a taxi to the museum, after we had visited City Hall. It was a wise decision, saving our energies for one of the most impressive one-person museums anywhere.

Edvard Munch was born in 1863, son of a moderately successful physician. The early death of his mother and two sisters had a profound effect and frequently inspired him to a theme of mortuary chambers.

His father moved to Oslo, and Edvard enrolled in the Royal School of Arts and Crafts. Much to his father’s displeasure, he was influenced by an against-the-grain polemicist who said that suicide was the ultimate path to freedom.

Edvard exhibited some portraits of his friends and then, in 1885, went off for a stay in Paris that had little impact on the young artist. He did see a Paul Gauguin show at the Café Volpini.

He received a travel grant allowing him to return to Paris. He and two other Norwegian artists arrived at the time of the 1889 World’s Fair (Exposition Universelle). The Fair included vast displays of art, including one of Munch’s own, Morning, in the Norwegian pavilion.

The Impressionists were riding high, but Impressionism had no lasting effect on Edvard. He was impressed by the work of Gauguin, Vincent Van Gogh and Henry de Toulouse-Lautrec and the way they evoked emotion through the use of color.

Munch’s father died. The family was left destitute. Edvard was depressed and harbored suicidal thoughts but returned to Norway to take care of the family when rich relatives refused to help.

After several shows in Norway, Munch was invited to exhibit in Berlin by the Society of Berlin Artists. It was the Society’s first one-man show.

The exhibition “evoked bitter controversy.” Nonetheless, Munch remained in Berlin for four years, a period that became the most important in his career. By then he had assimilated and discarded the lessons of Impressionism and was off on his own track to a form of Expressionist Realism. A decade of instability (1898-1908) followed that found Munch moving about between Norway, Paris, Berlin, Italy.

Munch’s life continued to be one of varying fortune, manic ups and downs, creative bursts. In 1907, he painted The Sick Child, a work showing his morbid interest in illness, agony, and desolation.

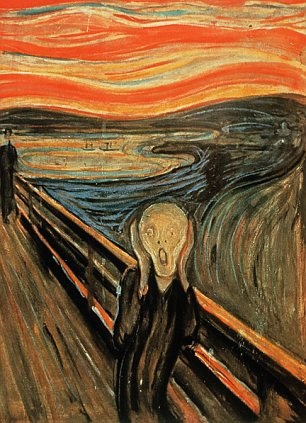

His most iconic work was The Scream, which he executed in four versions: two pastels and two paintings.

During his lifetime most of his work went unsold. When Munch died, he left his estate to the city of Oslo.

Oslo built the Munch museum, and that was what Anne and I and latter Frances and I went so far to see.

Only a part of the bequest can be shown at any time. Why? The museum owns 1,200 paintings, 18,000 prints, six sculptures, 500 plates (for making prints), and 2,240 books. That’s why, in 2008, the city of Oslo began planning for a much bigger new museum, which would be located near the Opera House, closer to the center of the city. The new Munch Museum is expected to open in 2018.

Before the first new museum was built, Reidae Revold was the curator in charge of the collection. I came across his name when I was writing my book on art frauds. But my sources were all Norwegian newspapers, which I couldn’t read.

Living near Washington, D.C., has its benefits. I took my newspaper stories to a cultural attaché at the Norwegian Embassy, and he translated them for me. He also taught me how to pronounce Munch. Or nearly so.

In Oslo, on April 23, 1968, Revald was charged with selling abroad 100 of the collection’s paintings and graphics for his personal profit. Revold had closed most of his transactions directly with dealers in West Germany and Switzerland, to whom he had written on official museum stationery.

Original Munch lithographs are extremely valuable, for the artist wanted them to have a rarity approaching that of his paintings and had printed only a few strikes of each rendering. When Munch died, some of his drawings were still on the stones, which remained in the hands of Munch’s printer until Revold obtained them, apparently in exchange for prints belonging to the museum.

Police suspected that Revold had made and sold new impressions from these stones. If so, the value of all Munch prints would have dropped drastically, as no one could be sure which prints were made under Munch’s own supervision. Not until the Norwegian government completed an investigation and determined that no fraudulent impressions had been made did the Munch lithograph market regain is stability.

In 2004, two paintings were stolen from the museum by masked and armed men. One of the paintings was The Scream. They were recovered two years later.

There have been a number of Munch forgers, including Casper Caspersens, but this “Moments in Art” is not about them.

In a 12-minute sale at Sothebys last May, one of the pastel versions of The Scream sold for $120,000,000, the highest price ever paid at auction for a work of art.

The Wall Street Journal claims that the buyer was Leon Black, an official with Apollo Global Management. Black reportedly is worth a bunch of billions of bucks.

So he didn’t have to go down screaming to get The Scream.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |