| Print | Back |  |

July 21, 2014 |

|

Moments in Art The Joy of Vision!by Lawrence Jeppson |

Editor's note: Today's headline is italicized and has an exclamation point at the end, because this is the title of a book that Lawrence Jeppson is writing about the artist whose life and works are the subject of today's column.

Before the Great War, art winds changed slowly. Esthetic impulses could not sweep the world in quick moments like avaricious hurricanes and then perish quickly like spent epidemics. New, sometimes revolutionary, art concepts sank tentative roots, grew painfully, flowered, spread, then ultimately weakened and were crowded out.

Usually, it was a drawn process in which the best never quite died but mutated in natural evolution. An art movement turning brown in its original field might still be only a seedling in another.

Air transportation began changing all that, speeding up the slow evolution. The internet and social media killed artistic evolution. A new thought can be echoed anywhere in the world the next day. Or even sooner than that.

Impressionism, born more than a century and a quarter ago in France, took 30, 40, 50 years to naturalize in North America. And in other countries. Many latter-day art observers, infected with the virus of the it-has-got-to-be-new cult, pay heed to only the first plow, the pioneer, believing no genius could flower in Impressionism after 1900.

They give scant credit to the horticulturalist who did come later to breed, cross-breed, adapt, and purify — simply because he/she came later. Since the artist came later he/she could not be original. Since the artist could not be original he/she could not be worth a whole lot of attention. So the circle says, so erroneously.

In America for the best part of a century the native Impressionists who crowded most of the art books and important museums had one blatant commonality. They had studios on the Eastern Seaboard, close to New York and Philadelphia, where they had easy access to the national art establishment.

Local boys got the glory, the standing, the preemptive notoriety.

Myopic, chauvinistic, and poorly financed, early art publications seldom acknowledged that talent lay elsewhere. Nor was there a plethora of formidable museums and art galleries in the hinterlands. Good painters from these far reaches were simply ignored. They had little way to pierce the Eastern establishment.

They would have to wait for history to catch up — long after they were dead.

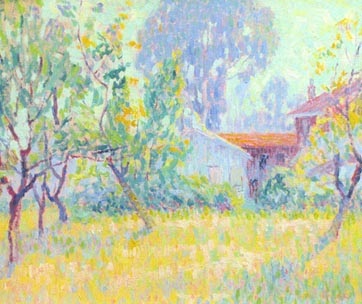

William Henry Clapp (1879-1954) was both a follower and a pioneer. He was also a horticulturalist, a measured scientist who took what Impressionism and Post-impressionism had to say — which he found in the original French fields of cultivation — and then cross-bred and pollinated and shared his seeds in Canada and California.

To be sure, chronologically Clapp was a follower. He was a generation younger than Monet, Renoir, Degas. His painting, though, never aped their styles, nor the styles of any other Frenchman. He was almost the same age as Pierre Bonnard (1867-1949) and Edouard Vuillard 1868-1940). The term follower should be no more derisory for him than it would be for them.

Clapp was a pioneer because he took his Impressionist vision into lands that were still overgrown with an earlier academia. Nearly 40 years after the first exhibition of Impressionism in France was forced to close because of public derision, the message of this new esthetic had not penetrated public Canada.

Clapp, back from four or five years of study and painting abroad, found his Impressionism too extreme for his native Montreal. The only sympathetic newspaper critic wrote, "Clapp paints what he thinks he sees and is not obsessed by what others see or think they see."

Neither his art nor a sympathetic critic could convince the public.

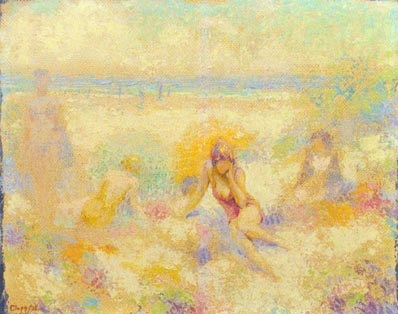

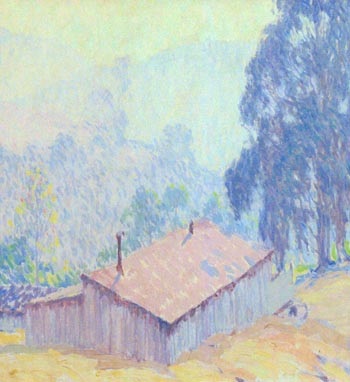

He found favor with his peers — but no one else. After spending two years in Cuba, Clapp fled to East Bay, 1917, where for the rest of his life he painted his landscapes and figure pieces as he saw them, became luminary and theoretician for a close-knit Society of Six, and for more than three decades ran a city museum, the Oakland Art Gallery, in four rooms in an upstairs corner of the Municipal Auditorium.

Clapp deserves credit as a pioneer, too, because in his years of museum stewardship he made certain that every legitimate art viewpoint, no matter how much in conflict with his own, had opportunity to search an audience.

To make sure of this he invented a three-jury system to judge conservative, modern, and radical art for the annual exhibitions. At one point hysterical women threatened to tear the museum apart chunk by chunk unless certain unflattering nude paintings were removed. Clapp stood by his guns.

Quietly fearless, he was the first museum director in the United States to give exhibition to the Blue Four — Jawlensky, Feininger, Klee, and Kandinsky — and he made his museum in the years thereafter the launching platform for American forays by this group and many others.

Yet William Henry Clapp is best seen today as the horticulturalist who took the seeds he brought from Europe and bred them so successfully to California light and vitality that they transcended regionalism and became part of a universal world of exquisite beauty.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |