| Print | Back |  |

June 16, 2014 |

|

Moments in Art Live Still Lifesby Lawrence Jeppson |

That title — “Live Still Lifes” — makes it sound like a dead bird hanging on a door should abruptly take wing and fly.

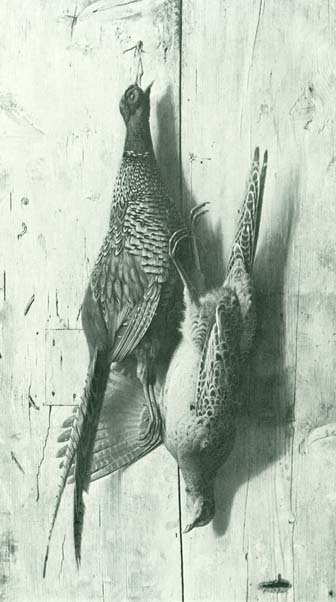

This still life by William Harnett of pheasants hanging on a weathered wood door once belonged to my friend Nat Leeb.

I’ve written about Nat several times, including my columns “The Unknown Cabbie,” “Birth of a Book,” and “Fabulous Find, Fowl Intrigue,” from which this sombre illustration was taken.

As I have said before, I consider Nat Leeb the finest French colorist painter of the 20th Century. But he was more than a painter. He was a collector, a big-time collector. If I were to list the artists represented in his holdings I’d need most of this column. His collection spanned four centuries of art.

Time and again we’d carpet pictures of his paintings across the desks of museum directors, and they could not believe the scope of the collection.

At one time I knew directors and curators of nearly every important American museum and a couple in Canada. These men and women were the connoisseurs in the art world. Most of them were specialists, and their expertness was often confined to a concentrated range.

Nat’s connoisseurship was not narrowly confined. He was a generalist. I never encountered anyone whose wide expertise surpassed his. Only a few seemed as gifted.

When Nat and his wife Paule came to the United States to begin with me what turned out to be the first of our two-month, country-wide tours of American museums, they brought their two-year old daughter and a governess with them. The daughter and the governess, Vicky, stayed with my wife and our six children, while I absconded with the only family car.

Our tour ended on the day before Thanksgiving. After celebrating that holiday with us, the Leebs went on to New York City, where Nat rummaged around art galleries for a few days before they caught their boat back to France. He found a misattributed painting in fabled French & Company, took it home, and sold it for enough to pay all the expenses of the two-month trip.

I was close professionally to the Samuels family that founded French & Company in the 19th Century and still owned it, but I never told them how Nat had profited from their blindness.

Nat’s collection was notably strong in still lifes. When we first met I had no warm feelings for still lifes. My appreciation slowly changed, to the point that at one time I was considering writing a book about them. Fortunately, wisdom prevailed.

Nat explained to me that when artists paint a landscape or a portrait, they must cater to a patron or adjust to what the market is buying. But when an artist paints a still life he is painting for himself — painting what he wants to paint, painting in the manner he wants to paint.

This supposition can’t always be true, but it is what Nat believed, and his point was well taken.

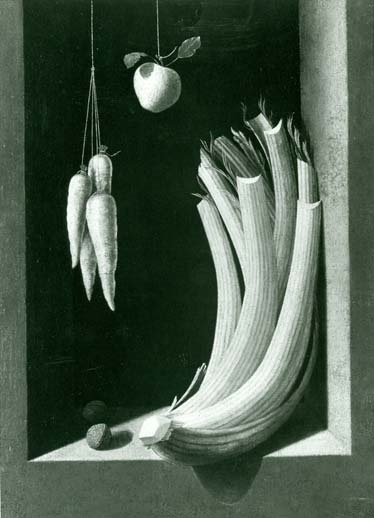

He ventured into still lifes himself, as this somewhat Surrealistic oil painted when he was only 16 demonstrates:

Sanchez Cotan (1561-1627) was the originator of Spanish still life painting. His influence on others was profound. Stefano Bottari, Encyclopedia of World Art, wrote, “As in no other country, still life in Spain was to attract the greatest artists.” He writes how Cotan, Zurbaran, and Velasquez led to Goya.

After Cotan entered Chatreux convent, however, he ceased painting still lifes and devoted himself to religious art. Until 1977, only seven Cotan still lifes were known in the entire world. That’s when Jose Gudiol, probably the foremost authority on Spanish art, published “The Still Lifes of Sanchez Cotan” in Pantheon journal in Munich.

The learned article expanded the number of still lifes from seven to nine, the two new ones being Nat Leeb discoveries.

I thought I had color illustrations. Can’t find. We must settle on a black and white:

X-ray examination reveals that originally the carrots were placed farther to the left, a test that rules out the painting being a copy.

Among Nat’s early Spanish still lifes were a pair by Juan Van Der Hamen signed and dated in 1621 and 1622. I won’t illustrate them.

Up north in France, Louise Moillon (1610-1696) was establishing herself as the first great French female artist. She was a master of still life art.

She was raised in a strict Calvinist family, which might explain why she painted still lifes instead of religious art, since Calvinists were essentially iconoclasts. Most of her work was done in the 1630s. Then in 1640, she married a prosperous timber merchant. She quit painting. Her last dated work was 1645.

Among Leeb’s many still life paintings was this particularly fine one by Moillon. I thought it should be in our National Gallery — or at least in the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C., a fine institution without much of an acquisitions budget.

Going back to Spain and ahead a couple of centuries brings us to the simplified and powerful still lifes of Francesco de Goya. Again we encounter Jose Gudiol, who in Paris gave me a copy of his guide to the art in the Prado Museum, Madrid. Gudiol wrote the definitive guide to Goya’s work, four very large volumes. Both of Leeb’s Goya still lifes are prominently there, including this one, Still Life, Military Hat, and Sword.

I met occasionally with Lester Cooke, the head curator for the National Gallery. He was one of my favorite museum people, perhaps because he told me he used my book on art forgers in his lectures.

I observed that the museum was weak in still life art and tried to get it to alleviate this lacuna by acquiring some of Nat’s collection. This was at a time when the museum was spending $100 million to build the new East building. To say the least, acquisition funding was not there.

Even if the funding were there, Cooke confided, J. Carter Brown, the director of the museum, did not like still lifes. It would be useless to suggest them.

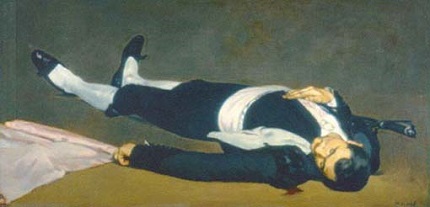

Cooke smiled wryly and said, “Of course, we do have one great still life painting.”

He referred me to the following painting:

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |