| Print | Back |  |

June 9, 2014 |

|

Moments in Art The Millet Family Folly, Part 2by Lawrence Jeppson |

A cute trick led to forgery on a grand scale.

Jean François Millet fathered a son, Charles Louis Millet, who became an architect. Charles Louis had a son, John Charles, who became a designer and a painter. As a young boy John Charles learned to forge his grandfather’s signature. His parents thought it was a cute trick.

The exact story of the Millet plot is difficult to piece together: the two prime participants never told the same tales.

In 1921, Grandson Millet was walking along a Paris street when he saw his grandfather’s Oedipus and the Sphinx in a shop window. He stormed into the shop and cornered the proprietor, Paul Cazot, a house painter from Avignon, and protested that the painting was not genuine. Cazot insisted that it was. The argument was heated, but despite recriminations and anger, some mysterious spark touched both men.

Grandson Millet came back for a second visit. The two men spoke with less hesitation and discovered that they could be enormously useful to each other. Cazot discarded caution and led Millet into the backroom, where he showed a number of fake pictures that he boasted he had painted himself.

Although Grandson was himself a Millet, he could not paint as well as Cazot. But Grandson had a gift for signatures.

Their operations were simple enough. Cazot would take the Metro to the Porte de Clignancourt and walk into the voluminous flea market, where he would buy old and worthless paintings of the Barbizon period. Scraping off or painting over the original images, Cazot would paint new “Millets.”

Usually Cazot would deliver the fresh fakes to Grandson Millet, who would sign and date them — and provide authenticating documents. Many of these certificates bore the forged signature of Architect Millet, his father.

As long as a painter is living he is considered the expert on his own work, but under French law when he dies this right passes to his heirs. Sons, nephews, spouse, mother — though they may be ignorant of what the deceased painted and unable to judge the authenticity of works attributed to him — suddenly are regarded legally as competent and qualified experts, and their opinions carry greater weight in the courts than do those of government-accredited experts.

More than one mistress (considered a relative under French law) has found her path thus opened to sudden fortune.

Grandson Millet’s fake certificates warmed the hearts of the most circumspect collectors. Frequently these certificates were written on letterhead stationery belonging to Architect Millet and purloined by Grandson Millet.

Besides forging papers and signatures, Grandson could perform another task better than Cazot: he could peddle the fabled but fake output.

With so many Millet forgeries by Notlay, Masson, Chaplin, and others still in circulation, gallery proprietors, museum directors, and collectors had to be careful not to be duped. But when pieces came to them from the Millet family itself, the authority seemed unimpeachable.

Usually Grandson Millet sold the paintings to legitimate galleries and had little contact with the ultimate purchasers. On an average a good “Millet” would bring him about $4000, which he would split with Cazot. He did not confine his merchandising to Paris but crossed the English Channel and built a thriving business with London dealers.

Money filled Grandson’s hands — and slipped through his fingers. He frequently spent Cazot’s share before he could deliver it. Cazot took to accompanying his partner across the Channel and collecting his share immediately upon completion of each transaction.

Disputes between the two escalated. Grandson Millet’s most successful outlet in London was the Thompson Galleries, which bought not only Millets but also the certificated works of other artists by the score. Millet collected $40,000 from Thompson for several paintings and claimed that he gave Cazot $20,000. Cazot complained he had received only $3,200. Thompson fared much better, selling one of the Millets for $60,000 (some reports said $72,000).

Grandson Millet, broke again, used a fake Millet as security for a bank loan. The bank became suspicious when the loan was not redeemed. When the bank offered the painting for sale an expert declared it was a copy. After Grandson was arrested, police tried to follow the painting’s path, but by then the bank, or a third party, had sold the painting to an American, whom it would not identify. End of case.

One of the pair’s most spectacular successes was the sale of 20 Millet canvases to the Musée de Barbizon, which specialized in Millet.

Through the decade of the 1920s, Millet and Cazot manufactured, authenticated, and sold paintings. As recriminations between the pair increased, Cazot sought ways to protect himself. Grandson had stolen Painter Millet’s signature stamp from Architect Millet. After borrowing it several times, Cazot persuaded Grandson Millet to sell it to him for a paltry 200 francs.

Painter Millet had created three versions of The Gleaners. (See last week’s column.) One was sold to an American, then destroyed by a fire. Using the much-reproduced Louvre version as model, Cazot painted a new one, Gleaner with the Red Hat, for which Grandson concocted a certificate of authenticity and a compelling provenance.

On April 15, 1930, a Paris dealer named Bourzat sold the canvas to a collector named Michaux for 150,000 francs. Lots of money, but a fatal blunder.

Signature-forging expert Grandson Millet had signed the painting at the top, which Painter Millet didn’t do. This oddity led to suspicion and then to investigation by the police.

There is another explanation, infinitely more French, of what first led the police to Millet and Cazot. Supposedly Cazot’s estranged wife stole one of her husband’s imitations, forged Millet’s signature herself, and tried to sell it. When apprehended, she had only to give her name and address to lead inquisitive police to the workshop door.

There the police found all the incriminating evidence they needed, including Painter Millet’s signature stamp.

Cazot declared that prosecution would be absurd because it would kill the picture trade in France.

The two cabalists were individually questioned the same day by the Examining Magistrate and gave wildly different responses. The exposure of the two men gave police a monstrous headache: how to track down all the fakes passed by the pair was an impossible task.

The Chicago Tribune reported that Millet had confessed to having marketed 3,000 forged canvasses. Other accounts said 4,000. Numerous pieces were still in dealers’ hands, but most had been sold and often could not be traced.

Five years passed before the case came to trial, and two more were absorbed in appeals and counter appeals. Millet and Cazot were cocky throughout their trial and treated the whole history of the previous ten years as a big joke. Grandson Millet bore the brunt of the punishment.

In the meantime, in 1930, Grandson Millet was arraigned for passing bad checks. In France, counterfeiting money carries a mandatory life sentence, frequently to Devil’s Isle, but issuing bad checks carried a maximum imprisonment of one year and a fine of only 50 francs.

In passing sentence — for Millet was found guilty — the judge scolded, “I wish I could give you more than a year. I consider passing bad checks the same as counterfeiting money. In America, bad-check passers get twenty years in jail.”

Grandson Millet shrugged his shoulders and smirked, “I shall know better than to give bad checks if I ever go there.”

Note: E. Benezit, the French 10-volume Dictionnaire des Peintres, Sculpteurs, Dessinateurs, et Graveurs gives painter Jean-Charles Cazin, who is not that well known, nearly two pages in very small type. It gives Cazot two lines, doesn’t know his birth or death dates, but says he was born in Avignon.

He was more famous briefly in Ogden, Utah, and a lot of other cities. This is the story that appeared in the Ogden Standard-Examiner on Sunday, 13 July 1930:

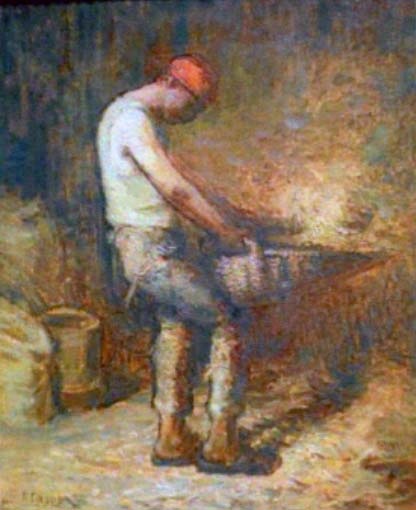

Observe the illustration in the lower right. In 2008, entitled Winnowing, the painting came up for auction as a Paul Cazot, who was identified as a 19th-century French artist. He was 20th century, but the painting was in the style of the 19th-century Painter Millet.

One wonders if the painting once was intended to be passed off as a genuine Millet. Indeed, might it have been — and then recovered and identified as a genuine Cazot. If it had been once passed off as a Millet, as a curiosity it might have been worth more than a post-trial Cazot.

The painting sold for $526 USD.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |