| Print | Back |  |

June 3, 2014 |

|

Rambling Thoughts on Church History Latter-day Saints and the Civil Warby James B. Allen |

Did you know that during the American Civil War, 317 men who were Latter-day Saints or would become Latter-day Saints in the near future served in the Union military forces, that 89 served in the Confederate Army, that one voluntarily fought for both sides, and that four were “galvanized Yankees” (Confederate soldiers who were prisoners of war and during their imprisonment, changed colors, and enlisted in the Union Army)?

Of those 411 men, 188 were Church members before the war, eighteen more are presumed to have been baptized before the war, eighteen were baptized during the war, 186 joined the Church after the war, and the baptismal date of one is uncertain.

These interesting statistics are only a tiny part of the story of Latter-day Saints in the Civil War era. That story may be found in a remarkable book published in 2012. It is titled Civil War Saints, edited by Kenneth L. Alford and published by the Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University in cooperation with Deseret Book Company.

Since the publication of the book, Alford has continued his research and the statistics above represent his latest update.1

The month of May 2014, marked the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Arlington National Cemetery. It was established during the Civil War and dedicated for the burial of American military personnel. This anniversary was one of the highlights of the Civil War Centennial that is still going on (2011-2015).

I thought this would be an appropriate time to comment briefly on some aspects of Latter-day Saints in the Civil War. I take the following from Alford’s 569-page book, but it is only an all-too-too-brief smattering of what is covered.

The book includes a short introduction, timelines of United States and LDS/Utah Territory history, 19 essays by various authors on a variety of subjects related to the Civil War and the Mormons, and eight very interesting appendices.

Obviously I cannot review or summarize all the essays here, but for your interest I have listed them at the end of this article. For now, just a few bits of information that are especially interesting to me.

Remember that during the war there was a lot of suspicion in Washington of the Mormons in Utah. Some people thought them disloyal, and many felt that they would tend to side with the South rather than with the North. And there were mixed attitudes toward the war in the Territory of Utah.

Although some Latter-day Saints were very much in favor of preserving the Union, others, including Brigham Young, at first looked at the war as a possible fulfillment of prophecy concerning the overthrow of the United States and a step in the preparation for the Saints to return to Jackson County, Missouri.

Nevertheless, Brigham Young made an important gesture of loyalty when he sent a telegram to the president of the Pacific Telegraph Company on October 18, 1861. This was a highly significant day in American history, for on that day the transcontinental telegraph line was completed as lines from East and West were joined in Salt Lake City.

For the first time, America had instantaneous communication from East to West. In his telegram Brigham Young declared: “Utah has not seceeded [sic], but is firm for the constitution and laws of our once happy country, and is warmly interested in such useful enterprises as the one so far completed.” For the most part, it appears, the Mormons wanted to prove their loyalty to the United States.

Various articles in this book refer to the reactions of the Saints in Utah to the war, and the various ways Utahns were affected by it. But in their article on the Lot Smith cavalry company Joseph R. Stuart and Kenneth L. Alford discuss what was the most direct way that the Church itself (or, more accurately, a group approved by the Church) was involved in military action.

Even though the federal government was reluctant to accept Utah Mormons into the military forces fighting in the East, there were things that needed to be done in the West, and that the Mormons could easily do. One was protecting the telegraph lines and Overland Trail from Indian attacks as well as attacks by the Confederate army.

The trail was vital for communications, for it carried not only people but also mail. It was the route of the telegraph line. In April 1862, President Abraham Lincoln asked the Secretary of War, Brigadier General Lorenzo Thomas, to send a telegram to Brigham Young asking him to raise a company of cavalry to serve for 90 days.

It is interesting that they asked President Young instead of the governor of the Utah Territory. Clearly this was because they knew that Brigham Young had much more influence over the Latter-day Saints than did Governor Stephen Harding. The telegram read, in part:

The company will be employed to protect the property of telegraph and overland mail companies in or about Independence Rock, where depredations have been committed and will be continued in service only till the U.S. troops can reach the point where they are so much needed.

Brigham Young was authorized to recruit around 90 men. They were to provide their own arms and other equipment as well as their own horses. He acted almost immediately. In less than two days he informed General Thomas that he and General Daniel H. Wells of the Utah Militia had acted on their request and that the enlisted soldiers had been sworn in by Utah’s chief justice John F. Kinney.

A Utah folk hero, Lot Smith, became captain of the Utah Cavalry, as the company was called. He had already been active in Indian wars and in the Utah War of 1857-58 where he became most famous in connection with his successful efforts to disrupt the progress of the federal army on its way to Utah in 1857. It seems ironic that he should now become a part of the federal army.

The Lot Smith company received instructions from the First Presidency that was unusual so far as military companies were concerned. They were told that they were to “recognize the hand of Providence” in behalf of the Saints. As emissaries of the Church, they were to “establish the influence God has given us… be kind, forbearing, and righteous in all your acts and sayings in public and private… that we may greet you with pleasure as those who have faithfully performed work worthy of great praise.”

This, they were told, would enable them to “again prove that noble hearted American citizens can don arms in the defense of right and justice, without descending one hair’s breadth below the high standard of American manhood.”

They were told to abstain from “card playing, dicing, gambling, drinking intoxicating liquors, or swearing” and to be kind to their animals. The company was also told that each “morning and evening of each day let prayer be publicly offered in the Command and in all detachments thereof, that you may constantly enjoy the guidance and protecting care of Israel’s God and be blessed in the performance of every duty devolved upon you.”

Ben Holladay, proprietor of the stage and U.S. mail line extending from Missouri to San Francisco, was delighted with the formation of this Utah cavalry unit. Because of Indian depredations the mail lines had been disrupted and some of his stations had been damaged as well as wagons and other equipment, and several employees had been killed.

He promised that as soon as the Utah volunteers were located along the line he would replace his coaches, horses, and drivers and rebuild and man the mail stations that had been destroyed.

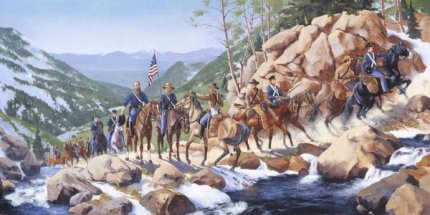

The Utah Cavalry embarked on its assignment on May 1, 1862. The following day, as they were camped in Emigration Canyon, they met with Brigham Young and Daniel H. Wells. These two spoke to them about both spiritual and practical matters, reiterating the important spiritual advice the First Presidency had given earlier.

President Young was very much concerned that the Utah soldiers would be loyal, obedient, patriotic, and good examples so that they would create positive impressions and perhaps some favorable reports in the Eastern press.

The company was assigned to go East as far as Independence Rock, in mid-Wyoming. It took them 26 days to get there. On the way they encountered various hardships such as ten feet of newly fallen snow before they got to Fort Bridger. They also found many roads almost impassable and they had rivers and streams to cross as well as considerable mud to contend with.

On the way they built three bridges in just four days. They found many mail stations still smoldering after having been destroyed by Indians and they saw wagon loads of United States mail scattered and destroyed. They could see clearly why they had been enlisted by President Lincoln.

After reaching Independence Rock the Utah Cavalry joined with the Eleventh Ohio Cavalry, which had also been assigned to protect the Overland Trail. However, one of the first assignments of the LDS soldiers failed. Three days earlier, at Ham’s Fork in Wyoming, some Indians had stolen several horses.

Lot Smith, along with twenty men and four pack animals, traveled the 150 miles to Ham’s Fork in only two days! They then proceeded on to the Green River but at that point Captain Smith decided that pursuing the Indians further was a “very considerable risk of life” and gave up the chase.

The Utah Cavalry spent most of the month of June at Independence Rock. The men participated in no significant military action, but they built a bridge as well as corrals and some houses at Devil’s Gate. Lot Smith reported that General James Craig was very pleased with their work and considered them the most efficient troops he had for that particular assignment. He even wanted them to re-enlist.

However, any thought of re-enlistment was squelched by Brigham Young, who felt it was not a good idea. One reason was that Colonel Patrick E. Connor and the California Volunteers were en route to Utah, with an assignment similar to that of the Utah Cavalry. But they would be stationed in Salt Lake City, which the Church leader considered inappropriate and insulting.

In his usual firm and forthright manner, Brigham Young said that “if the Government of the United States should now ask for a battalion of men to fight in the present battlefields of the nation, while there is a camp of soldiers from abroad located within the corporate limits of this city, I would not ask one man to go; I would see them in hell first.”

Lot Smith’s company moved to Fort Bridger, assigned to protect the trail between Green River and Salt Lake City. One of the assignments he received was to chase down five U.S. Cavalry deserters. Smith himself, along with first Lieutenant J. Q. Knowlton and nine other men, took up the assignment.

The article does not make it clear whether they caught the deserters, but it does tell of an interesting encounter with Washakie, a Shoshoni Indian chief.

Washakie was considered to be hostile to the Mormon settlers, and Smith wanted to do what he could to make peace with the Indians. It was with the “persuasion...of a loaded revolver” that they convinced a passing warrior to direct them to Washakie, who lived across Bear Lake.

They then discovered that the Indians had stolen a horse from Samuel W. Richards of Salt Lake City. Lt. Knowlton recognized the horse, captured it and then had a fight with the Indian who had stolen it. But the Indian eventually stole it back. However, they made it to Washakie’s camp, had a friendly conversation with him, and were convinced that he wanted good relations with the army.

When Washakie heard that a horse had been stolen he ordered that another one be given to Lt. Knowlton. He then had the horse thief severely whipped. Washakie also provided provisions for the soldiers’ return to Fort Bridger and asked them to take one of his relatives to Fort Bridger for medical attention.

Captain Smith thus reported to President Young that the company had followed the First Presidency’s council to establish peace with the Indians.

The company’s final assignment was its most harrowing. The following paragraphs are quoted directly from the article by Stuart and Alford (pages 137-138).

The night of July 15, Indians raided the ranch of Jack Robinson, a prominent settler near Fort Bridger, and stole nearly three hundred of his horses and mules. The Lot Smith company responded to a request to recover the animals. Sixty-one members of the company tracked the animals through the Snake River Valley.

The trip took longer than planned; the company ran out of provisions and was forced to live on wild strawberries. A group of twenty-one men under the direction of Lieutenant Joseph Rawlins returned home “by way of Fort Bridger” and arrived in Salt Lake City on August 2, 1862.

The remaining members of the company continued their difficult and dangerous search through the Tetons. While following the Snake River they were forced to swim nearly two hundred yards in deep water with a swift current.

As the detachment crossed the river, private Daniel McNicoll lost control of his horse, which was unwilling to swim across the strong current. Suddenly, McNicoll was pulled beneath the water’s surface. To the horror of his fellow soldiers, his body was carried downstream.

After a desperate search, McNicoll was declared drowned, but his body was never recovered. Because McNicoll did not die in combat, President Young’s promise that “not one of you shall fall by the hand of the enemy” was still fulfilled.

As the company continued on toward Salt Lake City, Captain Lot Smith felt highly distraught over the loss of Private McNicoll — so much so that one night he almost lost his appetite and spent the whole night walking the camp.

Their supplies were nearly exhausted and the company passed the date originally set for their separation from the service, July 29,1862. Smith and those with him finally arrived in Salt Lake City on August 15 — 107 days after their departure. The company was honorably discharged the following day.

Though this was only a short-term enlistment the company made a contribution to the war effort simply by helping to guard the Overland Trail. It also made a contribution to LDS history in Utah. It was a small economic boon to the Territory of Utah for the men earned more than $35,000 in wages and for other work, such as horseshoeing, blacksmithing, and other services.

In another interesting chapter, “Latter-day Saints in the Civil War,” Robert C. Freeman provides a handful of brief biographies of a few of those who served. One was Henry Wells Jackson, who was baptized in Nauvoo on January 28, 1844. In 1846, he became a member of the Mormon Battalion and was one of those who discovered gold in California.

He eventually made his way to Utah, married, moved to San Bernardino, then back to Utah. At one point he decided to go East to visit his father.

On the way, needing money, he hired himself out as a wagon master. Unfortunately, he was captured by Confederate forces and spent about three months as a prisoner of war. After his release he enlisted in Union forces, in the First District of Columbia Cavalry, beginning January 6, 1864.

Tragically, on May 8, his unit encountered an enemy unit near a bridge and during a fierce battle Jackson was severely wounded. He died on May 24 and was buried in the Hampton National Cemetery in Virginia.

A different kind of story was that of David H. Parry. Born in 1824, he was raised on his father’s farm and worked alongside the slaves as he grew up. Later he went into the merchandising business.

Eventually he fell in love with Nancy Higgenbottom. She was eleven years younger that David, but the two were deeply in love and after a brief courtship they married. The only problem was that they disagreed over religion. David was an agnostic but Nancy was a devout Latter-day Saint. His efforts to turn her against the Church amounted to naught, but a series of unfortunate events began to change him.

In May, 1861, their two-year-old son died from typhoid fever. The following year David joined the Confederate army but while serving there he came down with typhoid fever and was forced to return home. In 1863, both his mother and his father died, followed by his father-in-law. Then it was Nancy’s turn. She and another son died in the fall of that year. All were victims of disease.

David was devastated, but all this led him to begin to search for comfort and some kind of spiritual answer. He began to read some of the things his wife had left behind, including Parley P. Pratt’s Voice of Warning and some of the writings of Orson Pratt.

He was impressed, in particular, with the concept of eternal families and soon asked his mother-in-law where he could find the nearest Mormon elder. She directed him to Absalom Young, who lived twenty-five miles away, and in November 1862, the two cut a hole in the ice and David was baptized.

David soon returned to the army but, again, caught typhoid fever and nearly died. Then, while he was away from home, the Union army destroyed his home, store, and all its provision.

Discouraged, David and his brother-in-law left Virginia and joined with the Saints in Utah. There he married Nancy’s sister, Elizabeth, on April 10, 1865. They were sealed together for eternity in the Endowment House in November and on the same day Elizabeth stood proxy for Nancy to be sealed to David.

David became a successful businessman and also served in a variety of Church positions, including a mission in Texas, Tennessee, and Virginia (1875-1877), and president of Weber Stake (1877-1882).

But those who served in the military on one side or the other were not the only people who could be called Civil War veterans. In Appendix F, Alford lists twenty-two people who he calls “Special Civil War Veterans.” These included people whose service did not qualify them for regular listings as Civil War veterans.

As the author explains, “For example, teamsters and women could not qualify... because they were not given Civil War Veteran status. Other individuals could not be included because their Latter-day Saint baptism is uncertain or because they were not baptized as Latter-day Saints during their lifetime.”

One was Lydia Dunford Alder, who served as a nurse during the war but was not baptized until two years after the war was over. Eventually she became the first president of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association in Utah and she wrote several articles and poems for the Improvement Era. William Bagley is also on this list. He was baptized before the war and was part of Lot Smith’s Utah Cavalry, but, like several others on this list, was a teamster rather than a soldier.

There is much more to be learned from this book, as indicated in the list of chapters below. If you are interested, I think you will find reading the book most worthwhile.

Here is a list of the 19 essays in Civil War Saints:

“Prelude to Civil War: Utah War’s Impact and Legacy,” by William P. MacKinnon.

“Overview of the Civil War,” by Sherman L. Fleek.

“‘Have We Not Had a Prophet among Us?’: Joseph Smith’s Civil War Prophecy,” by Scott C. Esplin

“Abraham Lincoln and Mormons,” by Mary Jane Woodger

“Rumors of Secession in the Utah Territory, 1847–61,” by Craig K. Manscill

“‘We Know no North, No South, No East, No West,’: Mormon Interpretations of the Civil War, 1860–65,” by Richard E. Bennett.

“‘What Means This Carnage?’: The Civil War in Mormon Thought,” by Brett T. Dowdell

“The Lot Smith Cavalry Company: Utah Goes to War,” by Joseph R. Stuart and Kenneth L. Alford

“Protecting the Home Front: the Utah Territorial Militia during the Civil War,” by Ephraim D Dixon III

“What’s in a Name? The Establishment of Camp Douglas,” by Kenneth L. Alford and William P. MacKinnon

“Mormon Motivation for Enlisting in the Civil War,” by Brent W. Ellsworth and Kenneth L. Alford

“Indian Relations in Utah during the Civil War,” by Kenneth L Alford

“The Bear River Massacre: New Historical Evidence,” by Harold Schindler with addendum by Ephraim D. Dixon III

“Latter-day Saint Emigration during the Civil War,” by William G. Hartley

“Utah and the Civil War Press,” by Kenneth L. Alford

“Latter-day Saints in the Civil War,” by Robert C. Freeman

“Civil War’s Aftermath: Reconstruction, Abolition, and Polygamy,” by Andrew C. Skinner

“Mormons and the Grand Army of the Republic,” by Kenneth L Alford

“ This Splendid Outpouring of Welcome’: Salt Lake City and the 1909 National Encampment of the Grand Army of the Republic, by Ardis E. Parshall

1. The updates and more interesting information are found in Kenneth L. Alford, “Civil War Saints,” BYU Religious Education Review (Fall 2013), 6-9.

| Copyright © 2025 by James B. Allen | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |