| Print | Back |  |

May 21, 2014 |

|

Rambling Thoughts on Church History Wilford Woodruff: Fisherman, Hunter, and Missionaryby James B. Allen |

(Extended version of a talk given before a Historical Symposium of the National Society of the Sons of the Utah Pioneers, May 10, 2014)

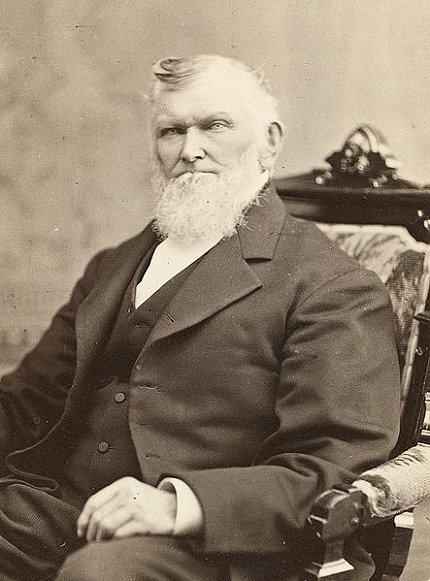

Wilford Woodruff, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 1889-1898, was a fisherman of the first order, but he also liked to camp, hike, ride in the mountains, and hunt. He was not an enthusiastic big game hunter, but shooting birds and rabbits was great sport for him. But his fishing and hunting was not just for sport--they were part of how he supported his family. He also liked to fish for men. What follows is a discussion of Wilford Woodruff as an outdoors man in general as well as a missionary.

Actually, for this presentation I could have just summarized a fine article on Wilford Woodruff as a fisherman, by Phil Murdock and Fred E. Woods, "I Dreamed of Ketching Fish: The Outdoor Life of Wilford Woodruff.," (1) Instead, however, I decided to study Wilford's journals myself and form my own impressions. As a result, I went through all nine volumes (2) looking for all the entries I could find on fishing, hunting, and the outdoors in general. It took an inordinate amount of time--over three weeks, in fact--but I had a lot of fun doing it.

There are literally hundreds of entries in Wilford Woodruff's journal that touch on these things. It is fascinating to see how frequently he recorded his fishing and hunting success, or lack thereof, in his journal, even if they were only incidental parts of a day filled with heavy Church and other responsibilities. He recorded not only the fact that he went fishing or hunting, but how many fish or birds or rabbits he caught as well as how many those who were with him bagged. Even if he did not go fishing or hunting on some days, he kept track of those with him who did, and what they caught. In addition, he frequently recorded in his journal detailed descriptions of the terrain and wildlife he saw in his travels. He subscribed to Forest and Stream, an important journal of the outdoors that focused on hunting, fishing, and other outdoor activities and was also one of the early promoters of conservation, especially wildlife conservation. (3) In 1895 he purchased Picturesque America: The Land we Live In, a two-volume work by William Cullen Brian with hundreds of illustrations. He also read books on fishing and wildlife. In January 1856, for example, he read Wild Scenes of a Hunter's Life, Including Cumming's Adventures Among the Lions and Other Wild Animals of Africa, etc. (4) The book had 77 chapters and 300 illustrations and covered not only Africa but also numerous other areas around the world. It contained vivid descriptions of hunting techniques and exciting hunting adventures. The several chapters dealing with elephants were evidently especially interesting to Wilford. The following paragraph from the author's preface must have captured his outdoorsman's imagination:

The lively and graphic narratives of Mr. Cumming, from which we have so freely borrowed, seem to open an entirely new era in hunting. His astonishing success in attacking whole herds of elephants and giraffes and assailing groups of lions and rhinoceroses, would seem to establish the principle that a bold front, quick eye, and unflinching nerve, will enable a single man to hold his ground, and destroy or disperse a host of the fiercest wild beasts. We commend the portions this volume copied from Mister Cumming's work to the special notice of the reader. The narratives may seem incredible; but we believe them; and the spoils of the chase brought from Africa by this daring huntsman, afford convincing proofs of the general truthfulness of his statements. (5)

"It was an interesting work," Wilford wrote in his diary. "It gave an account of the nature of all the wild Animals of Africa in the Hunt & nearly all animals in the world." (6) In 1894 he purchased a copy of American Fish-Culture: Embracing All The Details Of Artificial Breeding And Rearing Of Trout; The Culture Of Salmon, Shad And Other Fishes, by Thaddeus Norris.

All these interests combined with his day-to-day activities as a Church leader, family man, and farmer presents a fascinating picture of a sensitive, well-rounded, and deeply spiritual man with amazingly broad interests and talents--and, of special importance to the historian, an assiduous journal keeper.

On Thursday, August 18, 1892 Wilford Woodruff, at that time President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and his wife Emma began a ten-day camping trip, accompanied by his first counselor, George Q. Cannon and his wife. They rode the train from Salt Lake to Park City, then took a carriage ride to the Clayton camp (7) in the mountains near the headwaters of the Weber River. a total of sixty-five miles for the day.

The first thing President Woodruff did the next morning was go fishing, He caught six trout and also noted in his journal that he saw numerous grouse. (He called them chickens.) But the eighty-five-year-old Church leader was weary, and the next day he stayed in camp while his hosts, Tyler Clayton and his brother, went hunting for grouse.

However, the Claytons had a near tragedy. At one point, as Tyler was mounting his horse, his brother shot two birds but buckshot from his last shot struck a rock, ricocheted for thirty feet, hit Tyler in the throat, shoulder, hand, and knee and also struck his horse. "Marvellous that the shot did not maim the Man or horse," President Woodruff wrote in his journal. But at least the Claytons brought six trout back to camp that day, in addition to the grouse.

The next day was the Sabbath and the group held a sacrament meeting in the President's tent. President Woodruff opened with prayer, President Cannon administered the sacrament, and Church president then addressed the group, giving an account of his conversion to the Church and of his travels. He was followed by President Cannon.

Apparently President Woodruff did not feel well enough to go fishing or hunting during the next week. But he did not lie around doing nothing. He spent Monday reading but on Tuesday he had to take care of some business as John Henry Smith, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, and William Kimball came to the camp and spent two hours with him. At the same time he could not help but note in his diary that one of the Clayton brothers caught seven grouse that day.

The following day, August 24, President Woodruff again stayed in camp reading books and papers and writing. However, the Clayton brothers took off over the mountain to the north in order to fish in the Bear River, which originates in Summit County. (8) But as they crossed the mountain they ran into a wild hail storm that not only delayed them but almost resulted in near tragedy. When they returned at 9 o'clock the next evening one of them was so ill that, according to Wilford Woodruff's diary, he almost died. But they brought back 35 trout.

Meanwhile, President Woodruff did more than just stay in camp reading and writing. For one thing, he visited a spring in the vicinity of the camp and noted that he saw several black squirrels in the surrounding trees. "I did not know there was a Black squirrel in the Territory," he wrote. In this case he was mistaken for the black squirrel, as such, does not exist here. Most probably what he saw was a dark variety of the common red squirrel, for these vary widely on color and some become almost black.

He also visited other camps, one of them eight miles away, but on the night of Saturday, August 27, he had a bad night, recording that the altitude was too high for him to breath comfortably. The next day, Sunday, he and his party returned to Salt Lake City.

One thing President Woodruff did as he was relaxing in this mountain camp was write a letter to Forest and Stream, dated August 14. His letter is a remarkable illustration of the LDS prophet's avid interest in nature, wildlife and the outdoors in general. It began with a short biographical note emphasizing his lifelong penchant for fishing. He was born on March 1, 1807, he reported:

on the banks of a trout brook.... As soon as I was old enough to carry a fish-rod I commenced catching trout which I have continued to do, from time to time, for nearly 80 years.

Several years of my life were spent in Ashland, Oswego Co., New York, on the east border of Lake Ontario. While there I assisted, one morning in catching 500 salmon, very few of which were under 20 pounds, while a few weighed 40 pounds.

This was probably the native Atlantic Salmon, which is now extinct in Lake Ontario.

He briefly mentioned his first experience with fly fishing, then went on to discuss Utah's wildlife. When the territory was first settled, he said, it abounded in elk, deer, antelope, panther, mountain lion, and wild cat, as well as grizzly, cinnamon, and brown bear, often of immense size, and they were still found here and frequently killed. He said that he had never shot a bear, though in one instance a large grizzly, with two cubs, passed within thirty yards of him while he was concealed in the brush. At the time he held a muzzle loading gun in his hands but, he said:

the manner she treated her cubs, while apparently trying to wean them, plainly indicated the wisdom of my letting her pass unmolested, and assured me if I should fail to kill her the first shot, she would attack and kill me. Hardly half a mile after passing she came upon a camp, some of the men fired at her several times but she got away, with her cubs.

Here he was referring to an exciting encounter that took place on September 18, 1847, while he and others were on their way back to Winter Quarters from the Salt Lake Valley. They had traveled around 400 miles and were camped at Deer Creek, near present-day Glenrock Wyoming, where there was plenty of game. Wilford took his gun, apparently looking for game, and walked up the creek about two miles. Suddenly he came upon this huge grizzly quarreling, he said, with her cubs. "I did not think it prudent to approach her alone," he reflected in his journal, so he crossed the creek and climbed to the top of a high bluff. There he saw her working her way down toward the camp. After he returned to camp Brigham Young and three others went up the creek looking for a coal mine, coming within a little over 100 feet of the bear and her cubs before seeing them. Immediately the old bear took after them. Heber C. Kimball shot at her but missed. Ezra T. Benson could not get his rifle to fire. Brigham Young shot at the cubs three times with his 7-shooter pistol, which was ineffective. He hit one of them and knocked it down but it quickly got up and followed its mother who was coming up the bank toward the brethren. They quickly clamored up to a higher spot and the bear took off into the timber. But the men in the camp were not satisfied and, taking dogs with them, went after the bear. But darkness forced them to give up the chase. On the other hand, the hunt for game that day netted two antelope and two bull buffalo, as well as a buffalo cow shot by a Frenchman traveling with them. He shared it for supper and, Wilford wrote, it was excellent eating.

Wilford also noted in his letter that he had killed deer and antelope, though never an elk. He said that deer were increasing, elk and sheep were still in the mountains but difficult to get at, that deer, elk, and antelope were still plentiful in Idaho, and moose were taken occasionally. But his most extensive comments were about fishing in Utah, though the once abundant fish in Utah's lakes were diminishing as the human population grew. However, he had great hope in the hatching and planting of young fish in the lakes that was taking place. But as an illustration of how great fishing was in Utah generally he told the following story:

About 12 years ago I visited Bear River valley and fished 4 hours in a creek leading into Bear River, with a rod and reel, and caught 20 trout, four of them weighed a little over 4 pounds each. Upon this occasion I hooked and brought to sight, one trout, I think, of 10 pounds weight; but on account of the perpendicular height of the bank I could not land him.

He also extolled the abundance of wild fowl around Utah's lakes, ponds, and streams, though lamented that they, too, were diminishing. He ended with a reference to the camp from which he was writing the letter, told of killing 30 chickens (grouse) near their camp and concluded with the story of Taylor Clayton's hunting accident.

The significance of this letter, to me, is simply that it helps demonstrate not only this LDS prophet's avid lifetime interest in fishing and hunting but also how much he wanted other sportsmen around the country to know that Utah could be attractive to them. No doubt he was thinking back over his lifetime as he rested and wrote in that camp in the Uintah mountains.

For insight into Wilford Woodruff's entire life, and particularly his spiritual growth and contributions, I would heartily recommend Thomas G. Alexander's biography, Things in Heaven and Earth the Life and Times of Wilford Woodruff, a Mormon Prophet. (9) For the rest of this discussion, however, I will focus on fishing, hunting and the outdoors, under five headings:

1. The missionary fisherman and dreamer

2. The pioneer hunter and fisherman, 1847-48

3. Fishing and hunting on the underground

4. Fishing and hunting as part of family life and sustenance

5. Traveling and fishing in later life

I. The missionary fisherman and dreamer

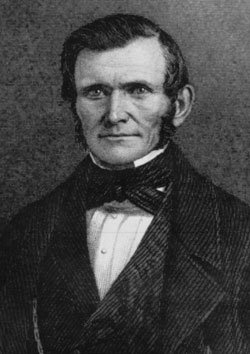

Wilford Woodruff's father, Aphek, owned a sawmill in Farmington, Connecticut, the town where Wilford was born in 1807. As a youth Wilford worked in the mill but he and his brothers also enjoyed fishing in the stream that powered the mill. As he grew older he became a seeker--one who was searching for true religion. In 1831 he moved to Richland, New York, where he encountered two Mormon missionaries in December 1833. On December 31 he was baptized. Almost immediately he began to devote himself to Church service, and particularly missionary work, becoming not only an avid fisher for fish but also fisher of men. Between January 1835 and November 1836 he served as a missionary in Arkansas, Tennessee, and Kentucky. His journals make no mention of fishing or hunting while on this assignment, but one entry shows his interest in observing the natural wonders around him. On January 15, 1835, two days after he left the Mormon settlements in Missouri, he wrote that he traveled "through some of the most beautiful praires mine eyes ever beheld inhabited ownly by wild beasts such as Deer and wolfs."

Things were different on his second mission, which lasted from May 31, 1837 to mid-1838 and took him to New England, where he spent most of his time in Maine, including the coastal Fox Islands. Just a month and a half before leaving Kirtland for that mission he married Phebe Carter, who actually joined him for a time on his mission. In August 1838 he learned that he had been called to the Quorum of the Twelve, though he was not actually ordained to that office until April 6, 1839.

During his mission he spent several days with Phebe's family in Scarborough, Maine, and it was there that he first wrote of a fishing expedition in his diary. On August 11, 1837, he got into a fishing boat with his brother-in-law, Ezra Carter Jr., and Fabyen Carter for an overnight fishing trip in the Atlantic Ocean. They ended up with 250 fish, including cod, haddock, and hake. He also saw four whales, to which he immediately added a religious note. As he recorded in his diary, "This was the first time I ever saw a fish belonging to that kind that swallowed Jonah." But it was not the most comfortable excursion he ever took: he became seasick.

In August and September 1837 Wilford and his companion, Jonathan Hale, were on South Fox Island, which was sustained largely by fishing. Wilford was impressed with the fisheries and could not help but describe them in his journal. There were great quantities of fish of all kinds, he noted on August 20, and he named nearly 50.

It may have been here that he began to think more seriously about the poetic imagery of being both fishers of fish and fishers of men. They crossed to South Fox Island on September 4 and were able to make an appointment to preach the gospel the same day. The next day they climbed to the top of a high ledge, had their morning prayers and, said Wilford, "O, what glorious contemplations vibrated our souls." Elder Hale read from Jeremiah 16:16 regarding the gathering of Israel in the last days: "Behold, I will send for many fishers, saith the Lord, and they shall fish them; and after will I send for many hunters, and they shall hunt them from every mountain, and from every hill, and out of the holes of the rocks." In that setting they could hardly help but think of themselves as those fishers whom the Lord promised to send. "Of a truth," Willard reflected, "here we were on an Island of the Sea standing upon a rock whare we could survey the gallant ships, and also the Island.... But what had brought us here? Ah to search out the Blood of Ephraim & gather him from these Islands, rocks, holes, & caves....While the sun shed his beams to gladden earth, the spirit of God caused our souls to rejoice." The two then read, sang, prayed, rejoiced, and conversed about the ancient prophets, about Joseph Smith and other leaders, and about the Mormon missionaries (Heber C. Kimball and others) who were even then serving in England. "Our souls rejoiced and we went our way with glad hearts," wrote Wilford.

Two days later the two fishers of men visited Benjamin Combs's flakes (platforms used for drying cod) where a thousand quintals of cod were spread out. (A quintal of dried cod is about 112 pounds.) They then walked to Carver's wharf where they saw a school of mackerel playing in the water, threw in some hooks and "had no difficulty in cetching a plenty of them." One wonders if this did not say something to them about the possibility of catching human fish.

Several months later at least one fish took on spiritual significance for the missionaries. On March 29, 1838 Ebenezer Carver was walking along the sea shore hoping for a sign as to the truth of the Mormon message but also contemplating the Savior's statement in Matthew 12:9 that "An evil and adulterous generation seeketh after a sign; and there shall no sign be given to it, but the sign of the prophet Jonas." Suddenly a large fish arose out of the water, some distance away, then sank out of sight. Carver wanted to see it again and the fish immediately reappeared, accompanied by another. One of them swam on top of the water straight toward Carver, looked at him, as Wilford described it, "with a Penetrating eye as though he had a message for him," then returned to its mate and the two swam away. Wilford hastened to note in his diary that this was the time of year that this particular variety of fish does not usually appear, and that they never come close to shore. Carter then had dreams confirming the experience and, of course, was baptized. "Great & marvelous are the works of the Lord," wrote Wilford. But Carter was only one of many people caught in the gospel net by Woodruff and Hale in the Fox Islands.

Wilford could not go home without at least one more good fishing trip at sea. On September 14, 1838, he was back in Scarborough, working to help new converts make ready to join the Saints in Missouri. That morning he went out in a fishing boat with the Carters and a few other people. Using clams for bait they "launched forth into the deep," as Wilford put it, and cast anchor about two miles out. The caught a few fish, mostly haddock, then headed for the beach. There they hung a pot over a fire, made a fish chowder, and, using clam shells for knives and forks, enjoyed "as rich a dish as would be necessary to set before a King." They then went out again, fishing until sunset and catching a great variety.

Wilford's mission to the Fox Islands was impressive enough, but during his first mission to the British Isles fishing and spirituality were became clearly combined.

This important 1840-41 mission had its origin in a revelation to Joseph Smith that called the members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles to leave Far West Missouri on April 26, 1839, on a mission "over the great waters" (D&C 118:4), that is, to the British Isles. Several of the Twelve met at the appointed time and place, Wilford Woodruff and George A. Smith were ordained to the apostleship, and after a summer of instruction by the Prophet and personal preparation seven apostles left for England. Wilford Woodruff and John Taylor, accompanied by Theodore Turley, were the first to make their way to England, arriving in Liverpool on January 11, 1840. Five other apostles arrived on April 6, and Willard Richards, who had been there as a missionary since 1837 and was then serving in the mission presidency, was ordained an apostle at their first conference. This made a total of eight apostles in the British Isles.

Wilford Woodruff went first to the Staffordshire Potteries, where he had some very satisfying success. But in March, as a result of the promptings of the Spirit, he went to Herefordshire. He was accompanied by William Benbow, a member of the Church in the Potteries, who introduced him to his brother, John Benbow. John belonged to the United Brethren, a very interesting group who were even then, like many "seekers" in America, searching for a restoration of the ancient gospel of Christ. It was here that Wilford had the most remarkable success of his entire mission. (10)

Almost immediately he began having dreams about fishing, and attaching spiritual significance to them. On the night of March 26 he dreamed of a river in which there were many fish. He caught some with a hook and then saw some large ones near the shore. He caught them, including an exceedingly large one. As he was taking care of them he saw a larger river that looked very much like the river near his home in Farmington Connecticut. On the other side was a boat with many fish lines attached. On one hook was a fish so large that the captain could not reel it in, so he sailed across the river to where Wilford was. The fish was taken out of the water and a bellman divided it, rang a bell, and each man took some. At that point one man said to another "I saw Baptizing last night. Was not you Baptized?"

Wilford was sure this dream meant something and said so on his diary: "What this Dream means time will soon Determin. There is to be much Baptizing done soon somewhare. Some of our Brethren will soon come from the U.S.A. & be divided among the people & I shall soon Baptize many & some noted persons."

He had good reason to feel this way. He had already met John and Jane Benbow and several of their friends but after his dream the conversions picked up. By mid-April he had baptized 158 people, including forty-eight United Brethren preachers. One of them was Thomas Kington, superintendent of the United Brethren organization. He and his wife Hanna were baptized just two days after Wilford's dream-inspired prediction that he would soon baptize some noted people. By early August there were over 800 members of the Church in that area, many of whom had been baptized by Wilford and more who had been baptized by converts-turned-missionaries, such as Thomas Kington. By the end of the year Wilford himself had baptized 336 people as a result of his labors in Staffordshire, Herefordshire, and London.

In August Wilford Woodruff, Heber C. Kimball, and George A. Smith opened missionary work in London. On the way there Wilford could not help but observe the scenery, which he dutifully wrote about. He seemed impressed with the Wychwood forest, a noted resort for sportsmen who wanted to hunt deer and rabbits. But he thought of London as a great Babylon and on August 18 asked himself "What am I & my Brethren here for?" The answer, given by the Spirit, was that they were to warn London of its abominations and exhort the people to repentance of their wickedness and prepare for days of calamity. He then let out an impassioned plea for help:

I am ready to cry out Lord who is sufficient for these things? O Mighty God of Jacob cloth us with thy power. Let the power of the Priesthood rest upon us & the spirit of our ministry & mission & enable us to warn the inhabitants of this city in such manner that our garments will be clean of their Blood & that we may seek out the honest in heart & the meek from among men & have many souls as seals of our ministry.

Ten days later, even though missionary work was not going so well, he had another dream of catching fish.

In September Wilford returned briefly to Herefordshire where, on the 21st, he attended a conference and was warmed by the general success in this mission field. It was probably with great emotion that he wrote the following in his journal:

This hath been a busy day with me & after standing upon my feet from morning till night I am called to shake hands with hundreds of Saints who possess glad hearts & cheerful countenances & it is with no ordinary feelings that I meditate upon the cheering fact that a thousand Souls have been Baptized into the New & Everlasting Covenant within half a year in one field which God has enabled me to open & I Pray God to Accept the gratitude of my heart for his mercies & blessings unto me in this thing & enable me to Stand with these Saints & all the righteous in the Celestial Kingdom of God.

He spent the night at the home of a Church member and, he said, after "standing upon my feet 8 hours in Conference, Conversing much of the time, Ordaining about 30, confirming some, healing many that were Sick, Shaking hands with about 400 Saints, waking 2 miles, & Preaching 4 hours in the Chimney Corner, I then lay down & dreamed of Ketching fish." Indeed, two of his favorite things, missionary work and fishing, were inseparably linked.

On Sunday, October 25th, back in London, Wilford Woodruff and George A. Smith preached at two meetings during the day but, Wilford said, this was the hardest place in which to awaken interest that he had ever visited. After the last meeting he walked five miles before he retired and then had another fishing dream. He saw himself at his father's house in Farmington. He decided to go fishing in the stream below his father's mill and caught many large fish with his bare hands. At that point his brother Asahel, who had been dead for two years, came to him and they and other friends began eating peaches and joyfully discussing the glories of immortality.

As if in fulfillment of his dream, the missionaries finally had a little success in London and on Sunday, November 20, they received some especially welcome news. The Reverend James Albion told them they could preach in his chapel and also informed his congregation that he was going to join the Latter-day Saints. Wilford baptized him a month later. "I thank God that there begins to be a little Stir in this City," he wrote. "We have had some good dreams of late about ketching fish & I hope we may soon realize it by Baptizing many Souls for we have laboured hard in this City for many weeks & with great expens & baptized as yet ownly 19 souls. But we will not despise the Day of Small things but hope for more."

That night he dreamed of caching fish, fowl, geese and turkeys in nets, and seeing a house on fire. Heber C. Kimball also dreamed of catching a good haul of fish in a net and also gathering fruit. "So I think sumthing will be done soon." Wilford wrote. Clearly they were both equating catching fish with making converts and interpreting their dreams as confirmation that they would be successful. They were fishers of men, and their mission was to bring as many as possible into the gospel net.

But catching fish was not Wilford's only kind of missionary-oriented dream. On Christmas Eve, 1840, for example, he dreamed of falling among thieves who tried to rob them, saying they had done something wrong in London years ago. Wilford told them that he had never been in London before but that he would preach to them if they opened their doors.

Five days later he dreamed of being in the midst of serpents but a tiger showed up and protected him from these enemies. He also noted that he had dreamed much lately of his two older brothers, Azmon, who had left the Church, and Thompson. On this night he saw himself in a barn looking for Azmon. He interpreted all this to mean that he would hear from his brothers soon. Interestingly enough, a little over six months later, on July 9, he received letters from both of them.

On December 30 he dreamed of serpents biting him. "We are begining to Stir the Devil up some in London," he wrote. Then, in an optimistic interpretation he said "We shall soon find enemies & opposition & may the Lord Hasten it for it will bring us friends." He thus welcomed opposition, believing it could only result in stirring up more interest.

At the end of every year's journal Wilford Wood included a remarkable summary of that year's activities. His 1840 summary shows how many people he and his co-workers brought into the gospel net. Clearly "fishing" had been good. His summary also lists the number of mobs that assaulted him (4) and other kinds of opposition: a kind of fulfillment of his dreams of being persecuted and of being bitten by serpents. He also expressed his deep gratitude:

Never have I spent a year with more Interest than 1840. Never have I been called to make greater Sacrifices or enjoyed greater Blessings.. . .

The whole year has been spent in a foreign nation combating error with everlasting truth, meeting with many contradictions of Sinners who oppose themselves against the Truth, Being Stoned mobed & opposed. Yet the Lord hath blessed me with a great harvest of Souls as seals of my ministry. Many hundreds have received the word with joy & gladness & are now rejoicing in the new & Everlasting covenant which Saints live in a lively hope of meeting in the Celestial Glory of our God.

His fishing dreams continued. On January 15, 1841, after eating a fish supper, he dreamed of caching many large fish with his hands then telling about it to a man who was putting up a gate. The man told him the interpretation: make haste and baptize as many as he could in London, set the Church in order, then "Seal up my testimony in the City & return home in the Spring." He left London in February, in the capable hands of a new missionary, Lorenzo Snow, and he left England on April 20.

There is little evidence that Wilford Woodruff did any fishing for fish during this first mission to England (11) but as soon as he got back to America he took another ocean fishing excursion with his Scarborough in-laws. On June 10 they caught over 200 fish, mostly haddock, and in the evening dined on rich haddock chowder and boiled clams.

His second mission to England was a different matter. In August 1844 he returned, with his wife Phebe, as mission president, remaining for two years. During that time he not only took time to fish but also learned of something that changed his whole perspective: fly fishing.

On May 7, 1845, he visited the little villages of Chatburn and Downham, where Heber C. Kimball had enjoyed tremendous success in his early 1837-38 mission and where, as he visited before leaving, the people flocked into the streets to greet them. Elder Kimball was moved to tears and pronounced a blessing on the whole region. Knowing of all this, as Wilford Woodruff entered Chatburn he said "I felt the spirit of God rest upon me while walking over the same road." In Downham, he met the 70-year-old Richard Smithies who, Wilford averred, was "the greatest fisherman in the country." Smithies was a fly fisherman and the next day, May 8, Wilford returned to Downham and went fishing with him in the River Ribble.

Until that point Wilford had known nothing of fly fishing. He apparently had been fishing simply by tying a line on the end of a rod of some sort, fastening a hook, baiting it, and tossing it into the water. As he learned about fly fishing he called it "the greatest art in fishing ever introduced." He described in detail Smithies's 14-foot-long rod with a reel at its butt end wound with line made of hair and a cat gut leader at the end. Having never seen a reel like this, he simply described it as "a small brass wheel with a little crank to it." Then, with obvious awe, he outlined the technique of fishing with flies:

One the end of the fine fish line is fastend 5 or 6 arti-fishal flies about 2 feet apart. These are upon a small cat gut almost as small as a single hair. 25 or 30 feet of the line is unwond from the reel at the but of the rod running through the rings to the point. The line is then flung upon the water the same as though it was tied at the end of the rod & the flies with a hook concealed in each swims down the stream. The trout instantly take it considering it the natural fly. They are hooked as soon as they strike it if they are large trout & run. They of their own accord unwind as much line as they want from the reel at the but of the pole or rod.

The fisherman does not pull the fish out of water on the bank by the pole but worries the fish in the water with the line untill he will not struggle. Then he draws him up to the shore by the line if he stands on the bank or to him if he stands in the water. He then takes a small hand net with a light pole 4 or 6 feet puts it under the fish & takes him vary deliberately out of the water....

It was the first time I had seen the fly used in my life in the way of fishing. I was delighted with it the rod & line was so light & flung with such skill & dexterity that the trout are beguiled & whare ever they are are generally taken. The fisherman has flies different for almost ever month calculated to imitate the flies that float upon the water at the time they fish. These flies are made of the feathers of birds some of various Colors. The trout will often take them before the natural fly. I was much gratifyed with this days fishing.

Smithies caught seven trout and two cheven (chubs, part of the carp family) while Wilford stayed with him. Wilford then returned to Chatburn where Sister Elizabeth Parkinson cooked the trout for him and the missionary traveling with him.

His next fishing adventure was near the town of Carlisle where, on May 19, he walked for ten miles with two Church members, Brothers Allen and Walker, and fished with flies in a creek for trout and salmon. They caught three small salmon but suddenly found themselves in trouble when an officer of the law appeared and told them they were fishing illegally and would be fined if they did not stop. But at least they had fish for dinner that night, though Wilford ate two of the three!

Wilford's diary does not indicate whether he did any more fishing on this mission, but he was determined to take fly fishing back to America with him. On December 10 he purchased everything he would need for both fly and traditional fishing: rods, reels, lines, hooks, flies, and equipment for both salt and fresh water fishing. The total cost was £6.2.4 (6 pounds, 2 shillings, 4 pence), a substantial price for someone traveling without purse or scrip and relying entirely on the Saints and other friends for sustenance! A British pound was worth about $1.72 at the time, which made his cost about $10.70. An online purchasing power calculator suggests that this would be the equivalent of $340 today.

When Wilford returned to Nauvoo in April, 1846, the city was in chaos and many of the Saints had already crossed the Mississippi and were headed West. He and his family crossed the river in mid-May, traversed the Iowa plains, and spent the fall and winter with the Saints at Winter Quarters, Iowa. In April 1847 he became part of the vanguard pioneer company that arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in July. On August 26 he began his return to Winter Quarters, along with Brigham Young and a few others. On June 21, 1848 he left Winter Quarters for Boston to preside over the Church in the Eastern States and Canada, arriving August 12. He stayed until early April, 1850, arriving back in Salt Lake City on October 14.

Serving as president of the Church in the East was Wilford Woodruff's final full time mission. But even though he kept extremely busy, he did not ignore his fishing. On September 14, 1848, he went fishing with a young man and caught 21 trout while the boy caught seven. On March 3 he received a visit from a Brother Whipple who reported to him that Utah Lake abounded with huge mountain trout, sometimes two or three feet long, and that all the mountain streams in Utah also abounded with fish. Since he had no time to fish when he was in Utah in 1847, this must have made him salivate as he contemplated spending the rest of his life there.

Meanwhile, on a few occasions he simply took time out from a busy day to indulge himself in fishing, while at other times he took off for a full day. On April 1, 1849, he did not fish but he spent several hours on the banks of the Delaware River watching professional fishermen catching shad (a species of fresh water herring), sometimes hauling in a hundred at a time. On April 27 he took time to fish in a pond, catching eight trout in just a few minutes. On May 2 he took enough time from his Church duties to go fishing and catch a few trout in a creek, then held a meeting and organized a branch of the Church later in the day. On May 21 he spent part of the day fishing, though caught very little that day. He had better luck on June 4 when he spent the day with Samuel and Josiah Hardy and caught eight trout, eight pickerel, and a few other fish. He was fishing again on June 19 with his brother-in-law and another man and the three of them caught 50 skulpins (fish that dwell on the bottom), 50 flounders, three cod, four eels, and two conners (actually bergalls, fish found in the northwest). Then, on June 26, he went out with a group fishing for codfish in deep water. They had a good haul but Wilford got violently seasick. However, that night he preached for two hours to a full house. On August 20 he fished in the river and caught four pickerel. He caught another 20 pickerel on September 17, as well as several other fish, and two days later he had a feast from the 15 pickerel and some 25 other fish that he caught that day. Then, in the evening held a meeting with the Saints. On January 4, 1850 he and three other men went fishing through the ice on a pond and caught 20 pounds of pickerel. The next day they caught 18 pickerel while fishing three different ponds. So far as his Journals reveal, this was the last time that Wilford Woodruff went fishing while a missionary.

For some reason, it was only during that first mission to the British Isles that his dreams and his fishing were tied together. What we see from all of this, however, is that for Wilford bringing people into the Church and fishing were both high on his list of priorities. Missionary work was the highest, of course, but it is little wonder that if and when he received special messages from the Spirit they sometimes came through dreams of fishing. That they came only in connection with that first mission might be explained simply by the fact that this was such an especially pivotal time, not only for the Elder Woodruff but for the future of the Church itself. (12)

2. The Pioneer Hunter and Fisher, 1846-47

We turn now to another set of circumstances under which Wilford did considerable fishing as well as hunting. This time, however, it was not just for recreation. Rather, it was a necessity. As he and his family crossed Iowa to Winter Quarters in the spring and summer of 1846, during that bitter winter in Nebraska, and during the summer of 1847, while he was on his way with the vanguard pioneer company to the Great Basin, hunting and fishing were necessary to maintain life. The same was true on the way back to Winter Quarters in the fall of 1847. As usual, Wilford often reported when he hunted or fished and what they caught, but the journal entries for this period do not seem to carry the same excitement as when he was hunting or fishing under other circumstances, and there was probably good reason for it. There is no time here to deal with all that happened while moving westward, but a few brief highlights will give you an idea of some of the things he did beyond his regular religious and other duties.

Wilford and his family forded the Mississippi River and began crossing the Iowa plains on May 16, 1846. They arrived at what would become Winter Quarters on July 26. During that time we see him involved in various activities simply to sustain life. On June 1 he shot a duck in order to make some broth for his ailing daughter Susan. On July 18 they were at the Big Pigeon River, which was well supplied with fish, so Wilford went fishing. At Winter Quarters, on September 3, he traded his gun to Amasa Lyman for a rifle, which was to come in handy in the near future. On September19 he shot six ducks but this outing was not a pleasant experience. He was at a lake and in order to retrieve four of them he had to wade through water and wesds for nearly a mile and he lost one of his shoes. He was wet, cold, and hungry by the end of the day.

October 5-7 found Wilford and several women on an expedition to pick grapes for making wine. They crossed the Missouri River, back into Iowa, where wild grapes are still very common. On the first day it took them until evening to arrive at the proper place, but on the way Wilford shot 3 prairie chickens. The women who would pick the grapes slept under the wagon that night, while Wilford went to bed under it. He had trouble sleeping, however, and finally went along the bank of the river hunting deer, wolves, and geese, but got nothing.. The next morning they had prairie chicken stew for breakfast. At the grape ground they found the grape vines entwined around cottonwoods and willows, so Wilford had to cut several of them down during the day. They picked grapes nearly all day, ending up with thirty three large barrels full. After they got home they made some 20 gallons of juice from the grapes.

The vanguard pioneer company was organized into groups of ten, with a captain over each. Wilford Woodruff was captain of the first ten. On April 7, 1847 his group left Winter Quarters to join the Camp of Israel on its historic trip to the Salt Lake Valley. The next morning someone shot a squirrel and, in good nature, proposed that since this was the first game killed on this important expedition it should be offered to their leader. Everyone agreed and the squirrel was presented to President Young for his breakfast. Later in the day Wilford and several others went hunting, but although they saw deer and wild birds they got nothing but "weary limbs and wet feet."

That was not a great beginning so far as hunting and fishing were concerned. But things got better, though sometimes hard. Here are a few of the scenes one encounters while paging through Wilford's diary for those tense and critical months.

April 20: the camp fishermen netted 213 fish and divided them among the members.

Sunday, April 25: Brigham Young instructed the camp that there was to be no fishing or hunting on Sunday, unless absolutely necessary.

April 26: Wilford went out with the hunters but killed nothing but one wild goose.

April 29: Wilford shot two of the four geese killed that day.

May 1: An exciting buffalo hunt. This was Wilford's first buffalo hunt, and it was a great one. Wilford, on horseback, was with a group that spotted a large herd in the bluffs along the route they were traveling. The men divided themselves into three groups, intending to approach the buffalo from the left, right, and center. Wilford was in the center group, which charged the buffalo and caused them to rush from the bluffs out onto the plain. Wilford rode up to the side of a buffalo cow and fired two balls into her. The other men with him also fired into her and finally she was killed. Wilford then rode to help another party that had wounded a buffalo. He then discovered that Orin Porter Rockwell had cornered three bulls so he and a Brother Pack rode to his assistance. Heber C Kimball also came to help. For a moment the bulls were surrounded, but they quickly bolted ahead. Wilford spurred his horse and ran ahead of them but when he was only about a rod away from them they pitched at him and began to chase him. He had to get out of the way in a hurry. Two of the buffalo then broke for a nearby bluff and Brother Brown followed them. Woodruff and three others stuck with the old bull, continued to fire shots into him, and he finally fell dead. They also shot the calf that was with him. Willard and Heber Kimball then chased after the man who had followed the two buffalo into the bluffs. Suddenly they saw the buffalo come out of the bluffs and run towards the main herd. They chased them for a while but their horses had run over ten miles already and were so tired the hunters were unable to continue the pursuit. But by the end of the day the group had killed eleven buffalo. That same day Joseph Hancock (13) went out hunting buffalo on foot. They were concerned that he did not return that night but the next day they found that he had killed a buffalo but stayed to watch it overnight so that the wolves would not get it.

Wilford made a special note of the fact that during part of the buffalo chase his hunting party dashed through a huge prairie dog town--the largest he had ever seen. According to his reckoning it was nearly ten miles long and two miles wide, and presented a serious danger. With burrows every few feet, a galloping horse could easily have stepped in one and fallen, perhaps injuring both itself and his rider. Wilford's horse stumble once but did not fall, and no serious accident happened which, he said, "was truly a blessing."

Sunday, May 2: A busy Sabbath. According to Wilford, they did no hunting because of the restriction on hunting on Sunday, but they spent much of the day cooking and saving the meat they had garnered the day before. They moved about two miles that day in order to camp on a better spot, and saw a herd of buffalo drinking at the river less than two miles away then moving back into the bluffs. Some of the men were eager to go after them, but Brigham Young said that it would be best to leave them be until the next day. But Wilford did not report the whole story. According to William Clayton's pioneer journal, sometime during the night a buffalo and calf came near the camp. The guards saw them and shot at the calf, but only wounded it. They caught it, however, and tied it up near the wagons, but finally decided to put it out of its misery and kill and dress it. Also that day some of the men went out with Hancock to pick up the meat that he had tried to preserve from the wolves.

Monday, May 3: More buffalo hunting. The hunters went back into the bluffs to find more buffalo and other game. Wilford started out with the group, even though he had a severe cold. He was also hurting from Saturday's chase and finally went back to camp. He was in great pain the rest of the day. Meanwhile, other hunters brought in three buffalo calves and four antelope. All-in-all, their Saturday and Monday hunt was very successful

May 14: An interesting day but a less successful buffalo hunt. Wilford went out to hunt early in the morning and hid himself in a bank of the Platte River. It was not long before a herd came along but, he said, the old bulls were acting as front and rear guards and none of the young animals were near enough for him to shoot. Then a group of seven bulls came along. He shot at one of them but missed. Disappointed, he went back to camp, had breakfast and, after a rain shower, went out again, this time with Phineas Young. (14) They looked for buffalo and antelope but as Wilford was searching among the bluffs he got lost. Apparently Wilford got nothing that day, but Phineas shot an antelope and Wilford carried it back to camp. Only one buffalo and three antelope were killed that day.

June 7: Wilford tried but failed to catch some fish.

June 16: Wilford shot his first antelope.

July 8: Wilford Woodruff became the first person to fly fish in what is now the western United States. The group had camped at Fort Bridger and that morning Wilford decided to try his luck at catching fish in the nearby streams, even though someone at the fort told him there were very few trout in them. Several of the men were already on the streams trying their luck with hooks baited with fresh meat or grasshoppers, but nothing seemed to work. Even though he had learned about fly fishing two year earlier, in England, Wilford had never tried it, or seen it tried, in America. He cast his fly into the water and, excited as a child with a new toy, watched it float downstream with, he said, as much interest as Benjamin Franklin had in his kite as he tried to draw lighting from the skies. Then, he wrote, "as Franklin received great Joy when he saw electricity or lightning descend on his kite string in like manner I was highly gratified when I saw the nimble trout dart my fly hook himself & run away with the line." But Wilford patiently worried him back and drew him to shore. He continued to fish for a while that morning, then returned in the evening and caught a total of twelve fish for the day. The rest of the camp caught very little, "proof positive to me that the Artificial fly is far the best thing now known to fish trout with," wrote Wilford in his journal.

July 12: Wilford tried his hand at fishing again, from the river bank as well as from the middle of the stream on horseback but this time he had "all sorts of luck good bad and indiferent."

July 16: he caught one trout for Brigham Young, who was not well.

July 17: He caught several trout with the fly.

July 18: Despite the restriction on Sunday fishing, this day it was a necessity. Several of the brethren went fishing and caught several large trout; Wilford caught two.

July 21: Wilford caught eight trout with the fly, after wading two miles in a creek.

July 24: Standing at the mouth of Emigration Canyon, Wilford viewed Salt Lake Valley for the first time and later described an idyllic picture in his journal. In a passage especially suited to his nature as a sportsman he writes:

we came in full view of the great valley or Bason [of] the Salt Lake and land of promise held in reserve by the hand of GOD for a resting place for the Saints upon which A portion of the Zion of GOD will be built.

We gazed with wonder and admiration upon the vast rich fertile valley which lay for about 25 miles in length & 16 miles in wedth Clothed with the Heaviest garb of green vegitation in the midst of which lay a large lake of Salt water of [ ] miles in extent in which could be seen large Islands & mountains towering towards the Clouds also the glorious valley abounding with the best fresh water springs rivlets creeks & Brooks & Rivers of various sizes all of which gave animation to the sporting trout & other fish while the waters were wending there way into the great Salt lake. Our hearts were surely made glad after A Hard Journey from winter Quarters of 1,200 miles through flats of Platt Rivers steeps of the Black Hills & the Rocky mountains And burning sands of the eternal Sage regions & willow swails & Rocky Canions & stubs & Stones, to gaze upon A valley of such vast extent entirely Surrounded with a perfect chain of everlasting hills & mountains Coverd with eternal snow with there inumerable peaks like Pyramids towering towards Heaven presenting at one view the grandest & most sublime seenery Probably that could be obtained on the globe.

Thoughts of Pleasing meditations ran in rapid succession through our minds while we contemplated that not many years that the House of GOD would stand upon the top of the Mountains while the valleys would be converted into orchard, vineyard, gardings & fields by the inhabitants of zion.

So ended the pioneer trek that began a new era in Latter-day Saint history. Wilford would soon go back to Winter Quarters for his family, then go to preside over the Church in the East. But in the mid-1850s he would be back in the Great Basin, where he would spend most of the rest of his life. There he would help found new communities, function as Church historian, become temple president in St. George, and travel and preach widely. In addition, he was active in community affairs but he also had to earn a living and care for his multiple families. He tried merchandising for a few years but, for the most part, he farmed and herded livestock. He also happily found time to hunt and fish, though, as pleasurable as these things were to him, they were also necessities as part of caring for his family.

3. Hunting and fishing as both Sport and Necessity

I was impressed when I read Wilford's synopsis of all his labors in the year 1865. That year he traveled 1,983 miles, attended 170 public meetings, preached 64 discourses, attended two General Conferences, participated in 62 prayer circles, ordained four Seventies, blessed 52 missionaries, spent 54 days in the Endowment House, gave 1342 endowments, sealed 451 couples, attended the dedication of one meeting house, wrote 27 letters, received 24 letters, attended 40 days of sessions of the territorial legislative Council, attended a meeting of the Deseret Agricultural and Mechanical Society, attended as treasurer meetings of the Jordan River Irrigation Company, administered to 16 sick persons, and paid tithing of $229.57. This list only scratched the surface of all he had to do in the Historian's Office and a multitude of Church and other responsibilities. But in addition to the things he listed he added, very meaningfully, "I spent the rest of my time upon my farm & in My Garden laboring for the support of my Family."

Since Church leaders received little if any compensation in those days, Wilford had to spend almost as much time making a living as he did on Church work. His hunting and fishing was at least part of what he needed to do to put food on his family's table. Today sportsmen "catch and release" when fishing, as part of a conservation effort that began in the mid-twentieth century, but in Wilford's day, and under his circumstances, that would be unheard of.

His journal contains literally hundreds of entries referring to his hunting and fishing, and I have no doubt that there were other times that he did not even record. Fishing and hunting were also a family affair, for sometimes he went with his father and also at times with his sons. Here are just a few examples of his fishing over the years in Utah. For example, on August 10, 1852 he and his father went into Parley's Canyon, caught 39 fish and camped overnight. The next day they fished downstream for three miles, wallowed through tough thicket in order to stay by the creek, and between the two of them caught 203 fish. Such a haul would certainly feed them for a few days. On a one-day fishing trip on June 8, 1854 he and his father caught 40 fish. The two of them caught 40 more on August 11, 1854, while fishing in Little Cottonwood Canyon. On July 12, 1855 he, along with George A. Smith and Samuel Richards, took a net to the Provo River and garnered two bushels of fish. This was obviously not sports fishing. On December 12, 1872 he took his son Asahel, along with a friend, across the Jordan River to hunt rabbits. On December 17 he went to Randolph to be with one of his families there and two days later he took his son Newton hunting for game because, he said, they had no fresh meat. They hunted in vain all day, but in the early evening they finally found a flock of sage hens and shot five of them as well as a white rabbit. Over the years he also fished in the Bear River, the Logan River, the Provo River, Utah Lake, and many other streams and canyons in the Territory of Utah. Such fishing and hunting excursions appear frequently throughout his journals.

He caught all kinds of fish, including trout, chub, and carp. On November 19, 1887, he even began building a carp pond on his farm, even though he had never actually tasted carp. He finished the pond four days later. But it was another month before he ever ate carp. On December 23 he was one of about twenty prominent men who were invited to the home of Heber M. Wells, mayor of Salt Lake City, and treated to a carp dinner. "It is the first time I Ever tasted of Carp. We all pronounced them good fish," he wrote.

From July 4-19, 1890, Wilford enjoyed a family camping and fishing trip with his wife Emma in a camp on the south fork of the Weber River. Just getting there, a distance of 60 miles, wearied the President of the Church, but on July 5 he went fishing anyway. He caught only one fish, but the group his son Asahel was with caught 20. They all went fishing again on July 8, but caught very few. Two days later they went about three miles up the Weber River, which, at that point was very hard to reach. But the aged Church leader climbed down the steep bluffs to the water, tiring himself out. Nevertheless he started fishing, catching nothing at first but then catching six large fish in one hole. He spent the rest of the vacation in camp while others fished and hunted and climbed a mountain. This may have been the last such strenuous trip into the mountains that he ever took.

We could go on and on, but these few examples are enough to illustrate the pleasure, the family nature, and the economic need of Wilford Woodruff's hunting and fishing.

4. Fishing and Hunting on the Underground

Life was hardly idyllic in Utah, especially for prominent polygamists, like Wilford Woodruff, who were forced into hiding to escape being arrested by federal marshals. This happened three times to Wilford Woodruff. The first began in February 1879, a month after the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the conviction of George Reynolds and federal Marshals began to hunt down more polygamists. Wilford was forced to flee south to Arizona and New Mexico. This tantamount exile ended in March 1880 when prosecution subsided because of a court ruling that more stringent evidence was needed for prosecution.

His second stint on what came to be known as the "Mormon Underground" began in January 1885, after the Edmunds Act of 1882 spurred renewed prosecution in 1884. This time he spent nine months in Southern Utah, near St. George. It ended early in November when Phebe, his wife of 48 years, lay near death and he returned to Salt Lake City. She passed away on November 10. Especially heart-wrenching was the fact that he had to watch her funeral procession from hiding.

His third period of hiding began, in effect, in mid-May 1886 when he left Salt Lake City with members of his family for an extended trip in the Uintah Mountains where they spent considerable time fishing, enjoying the mountains, and staying with friends. In January he had come near to being arrested by group of federal marshals and he had been careful since then. His trip to the Uintahs ended after one of his children became ill during a side trip and, upon returning to base camp he learned that federal marshals knew where he was and were after him again. On July 22 he fled once again to southern Utah. He remained until he received a letter on July 6, 1887, from George Q. Cannon, informing him of the imminent death of John Taylor. "I spent this whole year in Exile," he lamented at the end of 1886, "and had not the privilege of Attending one public Meeting or Conference And have been deprived of officiating in any of the ordinances of the Church in a Public Meeting." He arrived back in Salt Lake three days after President Taylor died. But he had to watch the funeral procession from the same window through which he had watched Phebe's two years earlier. He was now, in effect, the leader of the Church, though he was not sustained as President of the Church until the First Presidency was reorganized in April 1889.

Wilford hated being on the underground, and his chafing was expressed in an entry in his diary for April 6, 1879, during his first exile. "The General Conference of the Church met to day in the big Tabernacle in the City of Salt Lake while I am in this barren Desert Country for keeping one of the Commandments of God viz the Patriarchal Order of Marriage. Will the next April Conference find me alive and a free man? God knoweth."

But he was able to conduct some Church business during these periods of hiding, and also found refuge in hunting and fishing. In fact, hunting and fishing were, in some instances, almost a salvation for him. During his first exile he and others took an extended trip into the San Francisco Mountains of Arizona, where he exulted at the beauty he saw in the forest and the abundance of wildlife. On April 26, 1879 he caught 20 fish at Black Falls. Other outings resulted in his shooting 2 rabbits on May 17, shooting at but missing both an antelope and a deer on May 23, as well as failing in his attempt to catch some wild turkeys, killing an antelope on May 26, another failed hunting trip on June 4-7, more success on June 9 when a companion killed an antelope, and then, after all this, a surprising statement in his journal for June 13: "I took a new horse to day went South & walked around pilot knob. I saw 3 deer & 2 Antilope & did not shoot at anything. I did not think it was right for me to kill wild game." Perhaps an experience he had earlier, on May 26, gave him second thoughts. As recorded in his diary: "I saw a vary large Doe Antilope. I shot her 125 yards through the Body & vitals and she run 300 yards over a ridge with her hind parts to me. I shot at her again and put a Ball from my Needle gun Clear though her Body Endways. The Ball Came out at her throat & she fell dead." Obviously the poor antelope suffered, and such a scene could have made him reconsider what it meant to kill such animals. But that did not turn him away from fishing or small game hunting, for numerous diary entries during the rest of his Arizona sojourn show him catching fish and shooting ducks and rabbits. And on January 23 he even tried to kill another antelope.

But perhaps the most interesting excursion of this period began on August 1, 1879. That day Wilford met Apache war chief Petone and accepted an invitation to go with him and seven other Indians to hunt for deer and antelope in order to feed their families. After camping out the first night, Petone painted himself to look like an antelope, put on a shirt striped like an antelope, and dressed his head with an artificial antelope head and horns. Wilford then followed him on horseback over hills, valleys, stones and brush. Petone and his band were successful in killing several deer and antelope. In one case Petone, in his antelope get-up, pretended to be feeding on grass and got near enough to an antelope to kill it with one shot. On Sunday, June 3, Wilford and the brethren with him stayed in camp while Petone and his band went hunting again. But Wilford prayed for Petone, that he might get enough meat for his family. Wilford also preached the gospel to him, and said that Petone was much interested in what he had taught him. But on August 4 an embarrassing thing happened. Four of the young Mormon elders accompanying the group asked Petone if he would smoke with them. Scandalized, Petone looked them in the face and emphatically said "No The Great Spirit has told me if I would not smoke nor Drink whiskey I should live a long time but if I did I should live but a short time." After that the Church leader told the young men that they should take that rebuke to heart and never again set such an example before an Indian. Unfortunately for Petone, he did not have as long a life as he expected, for he was killed in February 1881 by a rival band.

Wilford got in more hunting and fishing during this exile, but he also had one of the most powerful spiritual experiences of his life. On January 26, 1880, while on an eleven-day trip into the San Francisco Mountains, he received what is known as the "Wilderness Revelation." It dealt with the apocalypse to come, the holiness of plural marriage, the need for the Saints to remain righteous, and God's judgements on the wicked and the enemies of the Saints. The effect on him was overwhelming: "My head became a fountain of tears and my Pillow was wet as with the dews of heaven and sleep departed from me and the Lord revealed unto me our duty Even the duty of the Twelve Apostles and all the faithful Elders of Israel and the following is a portion of the will of the Lord made manifest to me while dwelling in a shepherds tent in the wilderness surrounded by the drifting snows of the mountains while wraped in the visions of the night." Two days later he was "again wraped in vision during a good deal of the night Concerning the destiny of our Nation and of Zion. It was strongly manifest to me the duty of the Apostles and Elders to go into our Holy places & Temples and wash our feet and bear testimony to God & the Heavenly hosts against the wickedness of this Nation. My pillow was wet with the fountain of tears that flowed as I Beheld the Judgments of God upon the wicked."

During his second stint on the underground he stayed in and near St. George, living with faithful friends. Among them were John and Emma Squires and William Aitkin. From the Squires home he sometimes went hunting quail, disguised as a woman with a sunbonnet and Mother Hubbard dress made for him by Emma Squires. He did not fool everyone, however, for at one point a neighbor recognized him as he was returning to the house. William Aitkin, who lived several miles away, had a fish pond, and Wilford spent many hours taking advantage it. He also spent time visiting elsewhere

Again his journal is filled with hunting and fishing stories--more fishing than hunting. I want to tell them all, but a few must suffice.

On January 30, 1885 he visited the Aitkin pond, apparently hoping to hunt ducks, only to find that two boys had set fire to the foliage around the pond, making it impossible to find a place to hid "to get the wild fowl or any other purpose." (By "other purpose" he probably meant hiding from the law if he had to, for sometimes the rushes around the pond provided a perfect hiding place.)

On February 17, while staying at Bunkerville, Nevada, he learned from a mail carrier that two men who appeared to be federal marshals were camped at Beaver Dam. Fearing that they were on the way to arrest him, he went with a friend to the Virgin River, where he spent the day. But he shot two ducks that day and then, about dark, after the men had passed town on their way to California, he returned to town. It appears that his fear as to who they were was mistaken.

On June 19, fishing in the Aitkin pond, he caught 60 fish. Ten days later he and four other men went to the pond, caught 30 fish killed 20 doves.

At one point he went on a camping trip to Fish Lake, about 335 miles north of St. George, which he thought of as "the greatest depository of Large fine trout of any body of water in the Rocky Mountains." On July 15 he caught 25 trout. Eleven days later he was at Clear Creek, where he also caught 25 trout. On August 8 he and a few others caught 100 fish, 3 quail and 7 rabbits at Aitkin's pond. Two days later he shot three quails and a rabbit somewhere nearby and on August 15, during a very hot afternoon, he killed five more quail.

On August 22 Wilford went to Pine Valley, northwest of St. George, where he helped a friend repair a mill and then, on April 26, went fishing in a nearby canyon. The borders of the creek were so full of brush, large rocks, and steep bluffs that it was almost impossible to travel and very difficult to get the hook into the water. It took him three-fourths of an hour to wallow through the brush, climb the rocks, and untangle his line, so that he could fish for only about a quarter of the time he was out there. But he caught twenty trout anyway (more than I ever caught on one day in Logan Canyon) and his friend caught thirteen. By the time the day was over, however, this 78-year-old Church leader was so weary that he could scarcely stand. Two days later he caught 22 fish in Grass Valley. On August 31, returning to St. George, he shot a gun eight times, mostly from his wagon, killing six rabbits, a quail, and a heron. He proudly reported in his journal something unusual: "I did not miss one during the 8 shots."

During his third stint on the underground Wilford arrived in St. George on August 7, 1886, after traveling nearly 450 miles from where he had been staying in the Uintah Mountains. He again indulged himself in fishing and hunting birds, mostly quail and ducks. Again, the Aitkin pond was the scene of much of this outdoor enjoyment. But one of his fishing trips may not have been so fun. On June 21 he was in Pine Canyon and caught 23 fish. But, he said, it was "very rough work" crawling through the brush and he ran a fish hook into his thumb and up to the hand. Brother Thomson, who was with him cut it out with a pocket knife. "It was quite painful," he wrote in what must have been somewhat of an understatement. He went fishing again early that morning, caught only one.

During the early part of that exile he did more hunting than fishing but between March and July 1887 he went fishing twenty-two times. By contrast, he met with the Quorum of the Twelve on only eighteen occasions during that year. Such were the problems of trying to run the Church and, at the same time, escape the machinates of what he considered an unjust law.

5. Traveling and Fishing Later in Life

In his later years, as Church President, Wilford took a few trips to the west coast, sometimes to California and other times to the Northwest, sometimes on Church business and other times for pleasure. On November 1, 1889, Wilford Woodruff, George Q. Cannon and others were in the midst of a pleasure trip in British Columbia, where they did some mild hunting and fishing. (Age was creeping up, and neither of them had the energy to do anything very strenuous.)

That day they took a fishing trip on the St. Mary River. Wilford caught seventeen small trout but the big news of the day was that George Q. Cannon, according to Wilford, "caught one of the first fish he ever caught in his life."

Five years later, on August 25, 1896, Wilford and his wife Emma, along with George Q., and Wilford's son Asahel and others, were in Monterey, California. Wilford, George Q. and Asahel rented a fishing boat for $5.00, and spent all day on the ocean. They caught about 200 rock fish and one red cod. Wilford could not help but comment on Cannon's success: "Brother Cannon profesed never to be a fisherman, but he caught his share to day." Four days later they were in Coronado, where they went fishing again, this time from the pier, but it was a hot day and they soon quit with little to show for it. On August 31, however, they took an excursion on a professional fishing boat which took them to the fishing grounds about eight miles out to sea. The captain tied five lines to the stern of the ship, explained that they were for trolling, and put Wilford in charge of watching them. "It was the most interesting fishing I ever had in my life," Wilford wrote in his journal. Within two hours they had some 600 pounds of fish, including Spanish mackerel, yellow tails and barracuda. Wilford caught the largest fish of the group and his wife Emma caught several and helped him haul in his. "It was the most exciting hook fishing I ever was in," he said. But what were they to do with all those fish? They gave them to their friends who were with them and who, in turn probably gave most of them away. But little wonder that they were all tired out by the time they got to their quarters that night.

The 89-year-old Church president, even though tired, had remarkable stamina for his age, but this was the last fishing expedition recorded in his journal. Over the next two years he had to curtail his activities, and only one more entry in his diary even mentions fish. On April 29, 1897, not feeling well, he went to the office and took care of some family business then went home and walked around his farm, mentioning especially his garden and his fish pond. I suspect he thought about his fishing days as he walked around the pond, and was tempted to toss in a line. But instead he took an hour's nap then took another walk, ate dinner, had family prayer and went to bed about 9:15.

In June 1898 President Woodruff, in failing health, traveled again to California in an effort to recuperate. But even there he planned to take at least one more ocean fishing trip. However, on September 1 he took a sudden turn for the worse. The next day he passed away, probably still dreaming of fish and looking forward to seeing again all those that he had brought into the gospel net but had gone on before him.

NOTES

1. BYU Studies Volume 37, Number 4 (1997-98), pp. 6-47. In addition, there is a short article by myself and Herbert Frost entitled "Wilford Woodruff Sportsman." It was published in BYU Studies Volume 25, No. 2 (1974), pp. 113-17. It reproduced in full a very interesting letter he wrote to Forest and Stream magazine in 1892.

2. Wilford Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff's Journal, 9 vols., ed., Scott G. Kenny (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1985). All journal quotations are from this publication, which was included in electronic format in Signature Book's New Mormon Studies CD-ROM.

3. In the early twentieth century it helped launch the National Audubon Society, was an advocate of the national park movement, and supported the U.S.-Canadian Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

4. John Frost, Wild Scenes of a Hunter's Life, Including Cumming's Among the Lions and Other Wild Animals of Africa, etc. Auburn: Derby & Miller, 1851. A later and apparently updated edition was published in 1855: John Frost, Wild Scenes of a Hunter's Life: or, The Hunting and Hunters of All Nations, Including Cumming's and Girard's Adventures. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1875, c1855. See Woodruff Journal, January 23-25, 1856. It seems apparent that Wilford was reading the first edition.

5. Frost, Wild Scenes, 4.

6. Entry for January 23-25, 1856.

7. I have been trying to determine, for sure, who the camp really belonged to. According to President Woodruff's journal he frequently spent time with Nephi W. Clayton, son of William Clayton, but during the camping trip he speaks of Taylor Clayton, "brother Clayton's" brother. So far as I can tell, William Clayton did not have a son named Taylor, so I am not sure just who President Woodruff was with at this time.

8. This river, which Wilford Woodruff often fished in, originates in the mountains of Summit County, follows a circuitous inverted U-shaped course around the northern end of the Wasatch Range and eventually becomes the major tributary of the Great Salt Lake. On its way it flows across the southwest corner of Wyoming, meanders along the Utah-Wyoming state line, turns northwest into Bear Lake County, Idaho, cuts through Bear Lake Valley, eventually turns south into Cache Valley, re-enters Utah, picks up water from at least two other rivers and enters the Salt Lake about 10 miles southwest of Brigham City.

9. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1991.

10. The story of this mission is told in James B. Allen, Ronald K. Esplin, and David J. Whittaker, Men With a Mission: The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in the British Isles 1837-1841 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992).

11. On March 19, 1840 he wrote that "I dreamed at night that Brother Thompson was dead & left a wife & two children. I caught a large fish." It is unclear whether he actually caught a fish that day, or if it was part of the dream. I suspect it was part of the dream, for there are no other references to actually fishing in this part of his journal.

12. See Allen, Esplin and Whittaker, Men With A Mission, chapter13, "Consequences," for a discussion of how tremendously significant this mission was for the Church.

13. Wilford Woodruff mistakenly identifies him as Solomon Hancock, but the only Hancock with this company was Joseph. He is correctly identified in William Clayton's pioneer journal.

14. Sometimes spelled Phinehas.

| Copyright © 2025 by James B. Allen | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |