| Print | Back |  |

April 21, 2014 |

|

Moments in Art Daum Dream Doomby Lawrence Jeppson |

Sometimes dreams are as brittle as crystal.

I began my column last week with the statement, “This is one of those stories that bites to the quick.” Actually, I experienced three such events. The story about the Jerusalem tapestries was actually the second in that series. I won’t write about the first, at least not yet.

This is number three.

The making of glass is as old as history. In time the combination of sand, air (blowing), fire (furnace), and water (cooling) evolved, until there were centers in Europe turning out lead crystal of fabulous quality and beauty.

Post-war Mormon missionaries serving in Belgium admired the unique crystal products of Val Saint Lambert and, if they could afford it, brought home a piece or two. Located on the Meuse River in Seraing, Belgium, Val Saint Lambert crystal began making glass in an old monastery in 1826.

I brought home an exquisite 6" vase that I was able to afford because a young woman we were teaching worked in Liège’s biggest department store and enjoyed an employee discount. While at the Bruxelles World’s Fair in 1958, my wife and I went to the factory store and bought a much larger pedestaled bowl, which was six times as expensive.

This is my 7" Val Saint Lambert vase. It is impossible to catch its astonishing and beautiful light refractions caused by the circles cut out of the red surface glass around the entire circumference of the vase. (Daughter Marian Stoddard took the picture.)

What set Saint Lambert crystal apart from all others was its technique of double-colored and cut crystal. The form was blown in very fine, clear crystal. Then this was covered with a second coat of colored crystal. The factory produced the finest colored crystal of any maker in Europe. Parts of the colored coat were then cut away, leaving glorious patterns and unbelievable light refractions.

Unfortunately, despite many efforts to save it, Val Saint Lambert recently went into its fatal bankruptcy. Companies like it — Baccarat and Daum in France, Orrefors in Sweden, and Steuben in America — sold their crystal through franchised galleries, jewelry stores, and high-end department stores, where they often had their own boutiques. They competed with each other, and in time, with lower-cost makers in Asia.

Although King Louis XV gave permission for the founding of a glass factory in the town of Baccarat in the Lorraine area of Eastern France in 1734, 89 years would elapse before the company received its first royal commission. Another dozen years passed before the company won its first gold medal, at the World’s Fair in Paris.

Begun as a maker of window panes, mirrors, and stemware, Baccarat installed its first furnace for making crystal in1816. Over the decades it built an outstanding reputation for producing stunning crystal ranging from table-top objects to huge chandeliers. In 2005, the company was acquired by Starwood Capital Group in the United States.

In 1876, Jean Daum, a notary, loaned money to a maker of household glass in Nancy (also in the Lorraine), but the company could not pay its debts, and in 1878, it defaulted to Daum. His son Auguste joined the management of an enterprise consisting of 150 workers. Another son, Antonin, soon joined his brother.

Like Baccarat, Daum built its reputation as a maker of the finest lead crystal, riding high on the crest of the art nouveau movement.

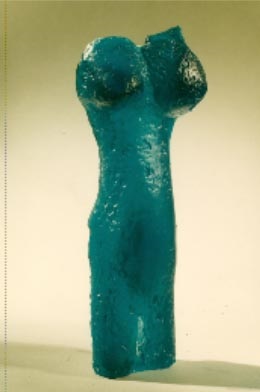

Carving out a 20th-century niche market for itself, Daum developed a proprietary process of making pâte de verre (glass paste) sculpture. The roots of the craft actually go back 3500 years to Egypt. Because the technique was very difficult, it was seldom used and largely forgotten.

In 1903, Daum, working with a specialist from the Sevres porcelain factory, devised a method of production. Some notable pieces were cast, but technical problems forced abandonment of the effort in 1919.

In 1965, Daum, impressed by the incomparable quality of pâte de verre, decided to try again. They worked for three years to perfect their process. Actually, pâte de verre was the traditional industry name. Technically, it should have been called pâte de cristal, since it contains 30% lead oxide, which gives crystal its clarity.

Pâte de verre manufacture has nothing to do with traditional glass blowing. It begins with an artist’s sculpture or model. A mold is made of the object. Colored crystal is poured into the mold at a temperature of 1800̊ Fahrenheit. The melted paste runs into every space inside the mold. The mold and its contents must be cooled slowly for four days. The mold is broken, and the cast figure emerges.

The crystal paste can be made any color by the addition of other metallic oxides. The craftsmen are so skilled that the figure can have subtle color shadings. Daum commissioned well-known artists to make table-top statues for execution in pâte de verre. Almost all the artists were well known in France but virtually unknown in the United States.

The medium required a certain abstraction. Elaborate, almost detached details could not be cast. Some figures were totally abstract.

Daum’s mission statement: “to make sculptures and other objects both original and modern in this material which is both translucid and colorful; to place these sculptures within reach of many art lovers who cannot own sculptures of well-known artists since they are generally prepared in a very limited number (1 to 9 copies)... and are generally priced very high.”

The pâte de verre pieces were produced in editions ranging from 50 to 200, each piece numbered, signed by the artist, and certified for authenticity. “Since they will be sent to all parts of the world, each art piece will be a rare piece of which the value will increase with time.”

Since crystal, compared with bronze, is fragile, Daum offered an unusual reassurance to owners. If a piece were broken and the owner returned the fragments and the certificate of authenticity to Daum, Daum would recast the piece at no charge to the unlucky owner.

In circumstances I do not recall in detail, an American businessman I had met the day before invited me to lunch at a friend’s hilltop villa in Rome. Daum makes more than pâte de verre, and he was a general agent for Daum in the United States.

An American art dealer in Rome headed for the Venice Biennial — my host must have figured mistakenly I was hot stuff! Well, I did represent all of France’s great tapestry artists.

Some days later I found myself in the Paris headquarters of Daum conferring with Jacques Daum himself, the president of the family-owned business. He gave me a portfolio of Daum’s editions bound in shiny, black alligator leather, from which these illustrations are taken.

To my surprise, Daum sounded me out about my taking over the development of the entire pâte de verre market in the United States, supplanting the man who had arranged the introduction.

I was flattered, but I declined. I was in no position to undertake the task. One of the impediments I pointed out: his artists were mostly unknown in America. (So had been my tapestry artists; so maybe this argument was a copout.)

We did come to one agreement. If I commissioned American artists, and paid the cost of production, Daum would produce pâte de verre pieces for me which I could market outside of Daum’s franchised dealers.

It was an exciting opportunity. All I lacked were the sculptors and the capital!

I took my quest to Les Taylor, a friend who lived in an upscale Bethesda neighborhood not far from the exclusive Burning Tree Country Club. He introduced me to his neighbor, who had his offices in the Old Town section of Alexandria, Virginia. I was destined to spend a lot of time there.

Mitch Mitchell was the perfect answer to my dreams. He was a master direct-mail marketer. He built high-rise apartment houses overlooking the ocean at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. And he loved glass. In fact, his hobby was cutting patterns into glass and crystal, a process akin to the famous cut glass of Waterford, Ireland.

Mitch said to me, “Don’t worry about the capital and the marketing. I can handle all that. You find the artists.”

Through Avard Fairbanks’s sons, Avard agreed that he would produce pieces for me.

After exchanging correspondence, I went to Utah to meet Dennis Smith in Highland. I had long admired Dennis. His depictions of family life (see the series at the Nauvoo Visitors Center) were beautiful and free of sentimentality. He also stepped out of his usual figurative mood and sculpted fabulous contraptions. Much of his work could not be done in crystal, but he would make pieces that could.

I was widening my search for artists. Everything was working out beautifully.

Then I got that stunning call from Les.

“Mitch just died suddenly!”

The crystal dream was shattered. I let the pieces lie.

Then, about 20 years later, as the country approached the bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth, Avard Fairbanks’s sons were considering ways that Avard’s many Lincoln depictions might be worked into the celebrations. Some of Avard’s Lincoln sculptures, adjusted to scale, would make marvelous pâte de verre pieces.

I wrote an inquiry to Daum, hoping to use the same arrangement I had made previously. But Jacques Daum was dead. My inquiry was misunderstood — and in fact rejected. It was a second sadness.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |