| Print | Back |  |

April 14, 2014 |

|

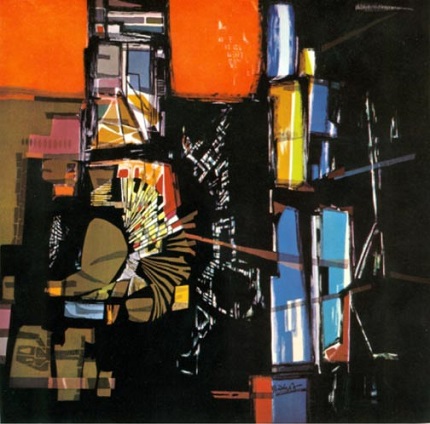

Moments in Art Warp and Weft in Jerusalemby Lawrence Jeppson |

This is one of those hard stories that bite to the quick.

French tapestry artist Mathieu Matégot (1910-2001) and I shared many experiences in France and in America from New York to Los Angeles, with Washington, Chicago, San Antonio, Houston, and Las Vegas in between. Of them all, Washington was his favorite city.

Matégot loved America, where his mother was buried. His older sisters had emigrated and lived in Manhattan and Princeton. At his own considerable expense he created a huge tapestry, First Step for Man, and gave it to the National Air and Space Museum in honor of America. But that is not the story I want to tell.

Usually, Matégot’s tapestries were woven in the south-central French village of Aubusson by the fabled weaving studios of Tabard Freres et Souers/Tabard Brothers and Sisters, which had been handed down from father to son since 1637. In Matégot’s time they were the Stradivarius of weavers.

Although Matégot was fiercely loyal to François Tabard, the Tabard atelier could not weave everything this prodigious genius turned out. Occasionally Matégot would create cartoons for another French weaver, most notably the Pinton workshops.

Matégot was the first tapestry cartonnier to introduce abstraction to the art form. His reputation soared on exhibitions and commissions as far away as Canberra, Australia. Weavers wanted the prestige and profit from weaving his cartoons.

Matégot produced huge tapestries for the National Factory of Gobelins in Paris.

Gobelins had been nationalized by Louis XIV. A commission from the government-owned Gobelins was a singular honor.

Matégot agreed to do a series of cartoons for a weaver in Portugal. I have one or two those tapestries. The weaving technique is not quite the same as the French, but the results are equally dramatic. Then the meticulous Japanese weavers in Kyoto pressed him into doing a cartoon or two. I have seen only pictures of these.

There was an Aubusson weaver named Goldstein who moved to Jerusalem and set up a weaving workshop just inside the old city. To be successful he needed the help of a world-class artist. He came to Matégot.

Producing tapestries is much more than finding artists to create the cartoons upon which the tapestry will be based. Dyeing wool yarns to the exact requirements of the artist is an arduous task—and costly. A bigger cost is paying the weavers.

Depending upon the complexity of the design, it takes a skilled weaver from one to three months to complete one square yard of tapestry.

Goldstein lacked the capital either to pay Matégot or finance the weavings. He turned to the artist for help. Matégot turned to me. I turned to the Jewish Community in Washington, D.C.

In Montgomery County, Maryland, where I lived, there is a large and prosperous Jewish community. Many have been dedicated to helping any legitimate enterprise that would add to the wellbeing of Israel.

I have been fortunate to have in my life good Jewish friends, from my days in the military to my settled life in the Washington suburbs and later in Salt Lake City. I think of Harry Wender as the personification of a good D.C. lawyer, long established and with a commitment to the community. (His relatives were founders of Auerbach's Department Store in Salt Lake.)

I learned a great deal about Jewish philanthropy and personal aid from Harry. He introduced me to the people of the national headquarters of B’nai B’rith in Washington and its museum. When I took the Jerusalem tapestry venture to him, he introduced me to a group of Montgomery County bankers and businessmen.

They were genuinely interested in a project which would give employment to Israelis and contribute to the arts. We began working out how to do this.

Then, suddenly, the 1967 Six-Day War broke out.

In 1967, Israel’s security was a great deal more tenuous than today. Its neighbors, Egypt, Lebanon, and Syria, supposedly had larger and better-trained militias. Times were tense, and there were threats to the young nation’s survival.

Israel decided to protect itself, and in a lightning six-day war destroyed the armies of its enemies, occupied Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula and the Suez Canal, and secured the West Bank from Jordan and the Golan Heights from Syria. Despite this initial military success, there was no certainty that enemies might not be able to regroup or that other Arab countries might not rally to their sides.

Israel was on a total war footing. That meant the Jewish communities everywhere else in the world marshaled to support the young country. Rallies and fundraisers were held. There was no money among American Jews to support a tapestry project in Jerusalem.

My Matégot-Goldstein project was finished.

Two or three years later I was visiting with my good friends Estelle and Peter Colwin in Philadelphia. For many years Estelle and I collaborated on a variety of art projects. She had close association with the Philadelphia Art Alliance and helped me arrange the first-ever United States exhibition for Tsing-fang Chen in this delightful museum.

It was for this event that I wrote my first book about Chen and coined the word Neo-Iconography.

I told the Colwins about my disappointment with the Jerusalem tapestry project. After listening and asking questions, Peter said, "Let me try to do something about that."

Although the Colwins lived in Philadelphia, Peter had offices in Manhattan. He was in charge of Christian liaison for an important national Jewish organization. I think it was the United Jewish Appeal, but it might have been another big group.

Later, Estelle called to tell me her husband was working seriously on the project.

Subsequently, Peter called and told me that he had everything worked out. The people or groups who would finance the project were all lined up and committed. He wasn't quite ready to tell me the details. He’d be back to me in a few days with all the information.

It never happened.

Peter Colwin suddenly dropped dead on a Manhattan street.

Estelle had no idea with whom Peter had been negotiating. Neither did Peter’s secretary nor any of his associates. The people with whom he had worked the Jerusalem tapestry deal never came forward.

The Matégot-Goldstein Jerusalem tapestry collaboration was gone forever. I regretted the death of the project. More seriously, I regretted the death of a good and trusted friend.

Later Estelle sent me Peter’s expensive hat and several other mementos.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |