| Print | Back |  |

March 17, 2014 |

|

Moments in Art Swiss on Wide Missouriby Lawrence Jeppson |

I was in Minneapolis in 1965, with my friend Nat Leeb and his wife Paule to open the first United States exhibition of Nat's paintings. This was held in a commercial art space and brought big crowds and good publicity.

The new Walker Art Center, a combination museum featuring contemporary art, a dramatic theater, and other arts, was not yet built. Started in 1879 as a personal art gallery by a lumberman, it evolved. Its modern 1971 building was dramatically enlarged in 2005.

Today it claims to be one of the five most important museums of modern art in the country, alongside the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim in New York, the Hirshhorn in Washington, and the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco.

Arrangements were made through old and new friends for a prosperous businessman in the institutional food business to be the intermediary through whom the Walker acquired a fine Leeb oil from the exhibition.

Begun four years after the embryonic Walker Arts Center, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts became one of the finest museums in the Midwest. It moved into its impressive Beaux-Arts building in1915, and despite subsequent expansion, only 4% of its 100,000 objects can be displayed at any one time.

If you add the fabulously modern building of the Wiseman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, people can feast on three memorable museums in the city.

After Leeb and I met with the director of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, we left his office to admire the many notable pictures on its gallery walls. We were about to make what was for me one of those unforgettable museum discoveries: a big show of the Indian and Upper Missouri watercolors and sketches by Karl Bodmer.

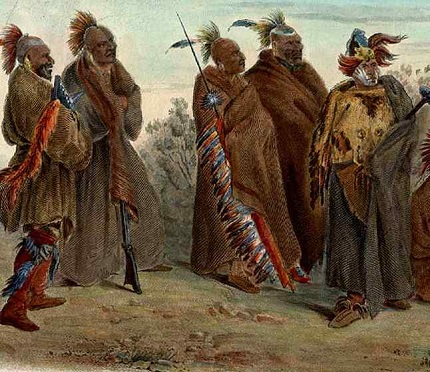

Two weeks ago I wrote about my introduction to the art of George Catlin when I discovered his Eight Years of Travel Amongst the Wildest Tribes in North America in a dingy London bookstore in1951. Although a generation younger than the American Catlin (1776-1872), the Swiss Bodmer (1809-1893) began exploring Indian lands the same first two years that Catlin did.

By the time I went with Leeb to the MIA I had heard of Bodmer and seen an odd painting or two. I was unprepared for the outpouring of that feasted my eyes. Leeb knew Bodmer only for his ordinary European career as an illustrator and printmaker.

Bodmer was born in Zurich. He was 13 when he began taking lessons from his mother's brother, who was a prominent engraver.

When he was 19, Bodmer moved to Koblenz, Germany. There he met a German naturalist, Prinz Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied (Prince Max, 1782-1867), who had led a successful scientific expedition to Brazil. The prince was an honored veteran of the Napoleonic wars and a dedicated student of the natural sciences.

Prince Max decided to repeat his adventure by taking his insatiable curiosity to America. Prince Max hired Bodmer and a servant, David Dreidoppel, a hunter/ taxidermist. They left on 17 May 1832.

In a letter written the same day, Prince Max wrote that Bodmer “is a lively, very good man and companion, seems well-educated, and is very pleasant and very suitable for me. I’m glad I picked him. He makes no demands, and in diligence he is never lacking.”

When they arrived in Boston on Independence Day, the entire northern part of the country from New England to Michigan was suffering a cholera epidemic. Three months passed before they could begin their voyage down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh.

The three men got as far as New Harmony, Indiana. Prince Max intended to spend only a few days in New Harmony, but his stay “was prolonged by a serious indisposition, nearly resembling cholera, to a four months’ winter residence.”

Young Bodmer had better health than the other two. In January he took off alone, down the rivers to New Orleans, where he spent a week with an Italian-American naturalist.

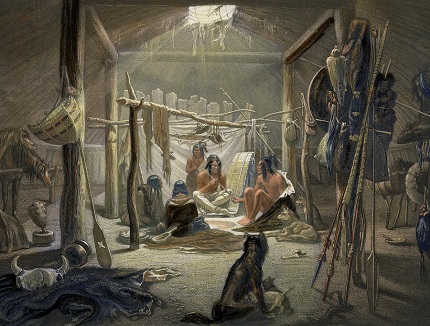

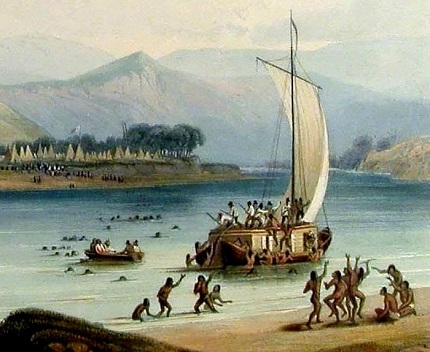

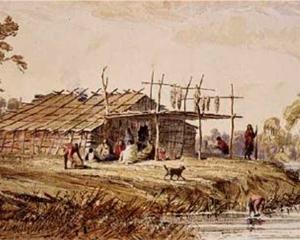

Returning to Indiana, Bodmer was again part of the Prince’s expedition. In April, 1833, they set out from St. Louis for a 2,500 mile journey by steamer and keelboat up the Missouri to what is now Montana. They spent a winter near a Mandan village. By the time they returned to St. Louis, they had spent a year on the upper Missouri. It was time to go home.

As expedition artist, Bodmer painted the Indians they encountered and the scenes that filled their eyes. He was the perfect visual recorder for the prince. He had a discerning eye and a substantial gift as a painter. He brought back 400 watercolors documenting the group’s travels. His training as an engraver would prove especially valuable back in Europe.

Bodmer moved to Paris, where 81 of his scenes from the expedition were published as aquatints. These were incorporated into the Prince’s memoirs published in London in 1839.

Bodmer settled in Barbizon, France, became a French citizen, and changed his name from Karl to Charles. Forty-four years after his expedition on the Missouri, he became a chevalier in the French Legion of Honor.

Bodmer's artistic career in Europe is pretty much forgotten. Until that day in Minneapolis, Leeb didn't think much of him, referring to him as an inconsequential Swiss painter. The Minneapolis Institute of Arts exhibit changed all that. Bodmer was one of those great early depicters of that part of America known as the Louisiana Purchase.

Appropriately, today one of the largest collections of Bodmer's watercolors, drawings, and prints can be found in the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |