| Print | Back |  |

March 4, 2014 |

|

Moments in Art Encountering Catlinby Lawrence Jeppson |

In 1881, Thompson and West published History of Nevada, a large and comprehensive volume. It was a treasure chest of stories and biographies of those early days in Nevada, from the vicious mining wars to the struggle to get the state admitted to the Union to give Lincoln added votes for his emancipation efforts.

It included the text of a threatening curse Orson Hyde put on a piece of land in Washoe Valley between Reno and Carson when that land and mill were stolen from him after he retreated to Salt Lake City in response to Brigham Young's strategy against Johnston's anti-Mormon Army in 1857.

While rummaging the backroom stacks of the State Library in Carson City, I discovered two copies. I was in high school in a small town, and the librarian knew me. Contrary to rules for reference-only books, she allowed me to take one of the copies home for several weeks.

[In 1952, I found a rare copy for sale in Elders Book Store in San Francisco. The price was almost $100. When I mentioned it to my fiancée, she tried to buy it as a wedding present, but by then the book was gone. A few years later she purchased a fine facsimile edition for me.]

Thompson and West ignited my interest in Western American history. I took courses in college and began collecting and reading relevant books. I enjoyed Bret Harte's Tales of the Gold Rush and wanted to tell that sort, only my area would be the Great Basin, especially the western edge of it along the Sierra Nevadas.

I enlisted in the U. S. Army at 17 and spent a great deal of time in the Army Specialized Training Program in civil engineering. Discharged, I came back to the University of Utah, where I was one of six who comprised the first group of graduates from the University's new Department of Journalism. I really wanted to write fiction.

I enjoyed several conversations with Walter van Tilberg Clark, who had already achieved literary fame with The Ox-bow Incident and Track of the Cat. Only later would I discover his masterpiece, now forgotten, City of Trembling Leaves.

We talked about Virginia City and the Comstock Lode, and he said that the place was full of stories he was going to use in future novels. As far as I am aware, none of these was ever written.

I won an unimportant place in a national short-short story writing contest sponsored by Writer's Digest and a gold medal for both prose and poetry from a literary society at the university. In a moment of inspiration, I wrote a Bret Harte-type story, "Injun Jim Loses a Pig." I think I wrote it in about two hours. In the many times I have reread it, I have never changed more than a single word.

"Injun Jim" was humorous but not hilarious, and today some people might consider it politically incorrect.

Between my graduation from Utah and my reporting to the mission home in Salt Lake City to serve for 30 months in the French Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I went home to Reno.

My father was an educator who encouraged his three sons to develop their individual talents.

Although I should have found a temporary job to help pay for my mission, he allowed me to hide away in the Reno basement for four months working on a Western novel. Today I don't know where the shards of that effort might be; in fact, I can't even remember what the novel was about. I did finish at least two Bret Harte-type short stories, "St. Clair Summons a Jury," and "Doc Zowie's Red Flannels."

At the end of my mission I traveled for two months from Rome to Helsinki, the first half on mission business. By the time Justin Fairbanks and I reached London to wait for our ship home, the money was pretty much gone. Even so, I spent several days rummaging through obscure antiquarian book stores in London's theater district. For years afterwards I would receive their sale catalogs.

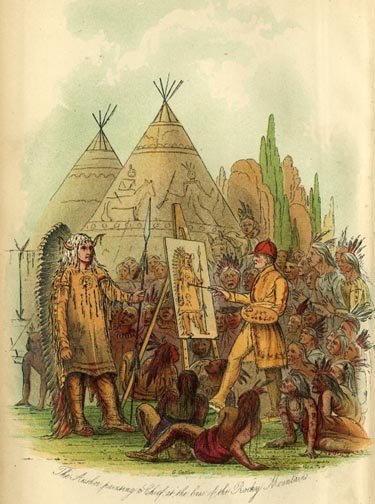

In one of these I found two weathered volumes, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians by Geo. Catlin. "Written During Eight Years of Travel Amongst the Wildest Tribes of Indians in North America. In 1832, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, and 39. In Two Volumes with Four Hundred Illustrations from the Author's Paintings. Third Edition, 1842."

The two volumes were published in London and are in need of serious restoration.

The text consists of 58 detailed letters -- Catlin's observations, adventures, maps, and black and white line engravings. I haven't opened them in decades, but I must have found material I intended to use in my stories, since there are several bookmarks in each volume.

The text is small -- it looks like six-point type. There was a time when I could read the tiniest printing. Today, Catlin's books are readable only with a magnifying glass.

Until I ran across those books in an obscure London alley, I did not know of George Catlin (1776-1872). Since he had not taken his art to the Great Basin, he was not within my geographical interest. The books introduced me to one of the two most important explorer depicters of the American Indians. The other was Swiss Karl Bodmer, but that's another story.

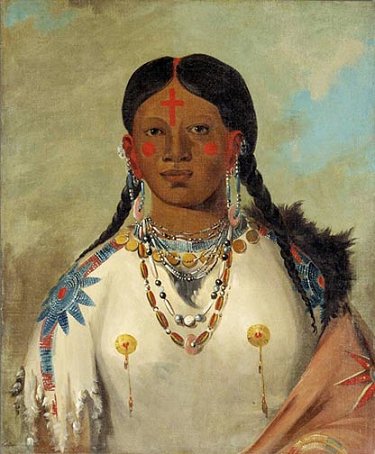

Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, Catlin grew up in a culture of hunting and fishing. Stories his mother told, including being captured by Indians, whetted his interest in collecting native artifacts. He was impressed by Indian delegations who came to Philadelphia, and he abandoned a legal career to record the appearance and customs of these "vanishing Americans."

In 1830, he joined General William Clark's diplomatic Indian mission up the Mississippi. Making St. Louis his base of operations, Catlin made five trips, 1830-1836, painting and recording his experiences visiting 50 tribes.

Then he made a 2000-mile journey up the Missouri to find and paint Indians and Indian culture among tribes who had been relatively untouched by American and European influences. Here he painted some of the best work of his career.

He made other forays into Indian lands, including the Great Lakes and Florida. As he wrote this Letters, made uncounted sketches, painted more than 500 paintings, he knew he was creating a unique and invaluable documentation of the native peoples.

He said, "I have, for many years past, contemplated the noble race of red men who are now spread over these trackless forests and boundless prairies, melting away at the approach of civilization."

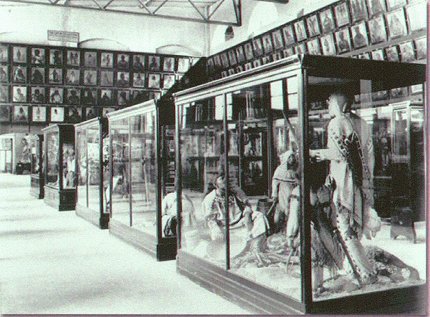

He exhibited his collection and lectured in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, New York, and other places to raise money, with insufficient success. He tried repeatedly to get Congress to purchase the collection. He had created an irreplaceable documentation. When Washington spurned him, Catlin took his collection across the Atlantic to be shown in European capitals.

Hoping to keep his collection intact, he continued to lobby the U.S. government. In 1852, coerced by debt, Catlin was forced to sell his original Indian Gallery of artifacts and 607 paintings to Industrialist Joseph Harrison. Harrison stored them in his steam boiler factory in Philadelphia.

Between 1832 and 1872, Congress voted on 10 resolutions to purchase the collection, one coming within two votes of passage.

In 1872, the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution invited Catlin to set up a studio in the Smithsonian Castle to continue to work on a series of cartoons he was making. Later that year Catlin died.

Joseph Harrison also died. In 1879, his widow, Sarah, made possible what Congress had failed to do. She gave Catlin's Indian Gallery to the Smithsonian.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |