| Print | Back |  |

January 20, 2014 |

|

Moments in Art The Real Sherlock Holmesby Lawrence Jeppson |

Meet the real Sherlock Holmes.

What has he to do with art?

Several weeks ago one of Utah’s Public Broadcasting System stations broadcast a two-hour program, “How Sherlock Holmes Changed the World.” It featured interviews with some of the best scientific crime investigators in the business.

Each one of these experts, avid Holmes readers all, tied their science directly back to Holmes’s careful observational tactics and use of technology, such as was known at the time, in solving crimes.

One of the experts was a Chinese American police examiner whose experience apparently began in Taiwan. He said, in effect, that before Holmes, police relied on getting confessions from suspected criminals and if suspects didn’t confess, sometimes they were taken to a back room and beaten until they did.

More exactly, convictions relied upon eyewitnesses, who were not necessarily reliable. “In England superstition, squeamishness, and emotional respect toward a dead victim prevented investigators from performing invasive procedures like incisions, thereby limiting the amount of data they could collect.” (“How Stuff Works”)

Using fictional characters, television has acquainted us with the work of these real-life criminologists. Sometimes the imagined characters solve cases quicker than can be realistic, but TV dramas have time constraints. The best of these focused programs have been the long-running “CSI” (Crime Scene Investigation), alongside “Bones” and the cancelled “CSI New York” and “Body of Proof.”

The two military forensic shows have been popular programs but less exacting in depicting police lab work and more on bang, bang.

Some of the scientific procedures depicted in these programs–and in many text guides to criminology–have been useful as part of the process in authenticating works of art, a subject I expect to examine a bit next week, with some of the stirring stories of art crime.

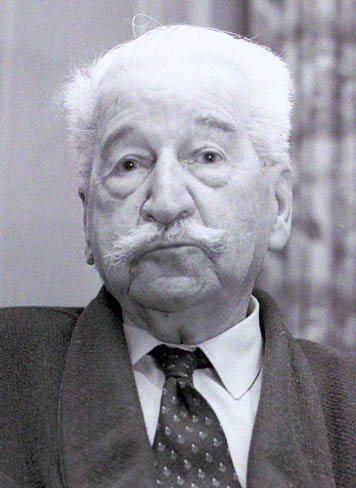

The fictional Sherlock Holmes began shaping real criminal investigations, but the evolution to full CSI took decades. The PBS program “How Sherlock Holmes Changed the World” repeatedly attributed modern criminology to a Frenchman, Dr. Edmond Locard (1877-1966).

I have often said, if Sherlock Holmes were a real person instead of an Arthur Conan Doyle fiction, he would be a Frenchman named Edmond Locard. Indeed, many have named him “The Sherlock Holmes of France.”

While studying medicine, Locard developed an interest in applying science to law. He wrote a paper, “La medicine legale sous le Grand Roi /Legal Medicine under the Great King.” He worked for a few years as an assistant to Alexandre Lacassagne (1843-1924), a physician, criminologist and professor. (Lacassagne was important in developing medical jurisprudence.)

Locard left to pursue a degree in law. He passed the bar in 1907, and went on to study under Alphonse Bertillon (1853-1914), a police officer famous for developing an identification system based on physical measurements. Until then, criminals could be identified only by photographs.

His contributions of mug shots and the systemization of crime-scene photography remain in place today. (In 1912, a paper that purported to establish that Bertillon was the founder of fingerprint science turned out to contain alterations and forgeries.)

In The Hound of the Baskervilles, a character refers to Sherlock Holmes as being second only to Bertillon as a detective. But Conan Doyle had not yet encountered Edmond Locard.

In 1910, the Lyon police department offered Locard a few small attic rooms where he could form the first police department laboratory so that evidence collected from crime scenes could be examined scientifically. These labs were to make him famous.

Sidetracked during World War I, Locard was put to work for the French Secret Service as a medical examiner. He was attempting to identify cause and location of death by examining stains, dirt, and damage to soldiers’ and prisoners’ uniforms.

Back in his labs, a stream of papers, books, lectures, and appearances followed. He would produce more than 40 books and articles in French, English, German, and Spanish. Among them was a highly influential seven-volume Traité de criminalistique. He founded the International Academy of Criminalistics in Swizerland.

Systematically, he clarified, expanded, and established the science of crime scene investigation. His work on developing better classifications, definitions, and use of fingerprints, 1914, is only one of his lasting achievements.

Every crime scene investigator, anywhere, uses what is known as Locard’s Exchange Principle, the transfer of evidence between objects: every contact leaves a trace.

Whatever [a criminal] touches, whatever he leaves, even without consciousness, will serve as a silent witness against him, his fingerprints or his footprints, his hair, the fiber from his clothes, the glass he breaks, the tool mark he leaves, the paint he scratches, the blood or semen he deposits or collects.

All of these and more bear mute witness against him.

This is evidence that does not forget. It is not confused by the excitement of the moment. It is not absent because human witnesses are. It is factual evidence. Physical evidence cannot be wrong, it cannot perjure itself, it cannot be wholly absent. Only human failure to find it, study, and understand it, can diminish its value.” (Dr. Edmond Locard, Crime Investigation: Physical Evidence and the Police Laboratory, Interscience Publishers, New York, 1942)

Because of the destruction of World War II, the French government imposed severe penalties on the owners of unoccupied living space. The Piaton family was among the most prominent in Boston-like Lyon, and they owned an apartment house that was so large it went clear through the block and had entrances on two parallel streets.

Various members of the extended family occupied apartments in the five-story building.

The matriarch of the family was Madame Piaton. One of her apartments on the third floor contained two large, unoccupied bedrooms. To avoid the penalties, she rented these two rooms to four Mormon missionaries.

Elder Delbert Johnson, a big, strong farm boy from Barnwell, Alberta, Canada — one of the finest elders I ever worked with — and I occupied one of these rooms. It had two small balconies overlooking Quai de Serbie and the wide, cold, rushing Rhone river.

When Vincent Auriol, the first President of France’s Fourth Republic, visited Lyon, his motorcade came down the street under our window while we watched.

Madame Piaton gave us the help of a maid who brought us breakfast each morning (fashioned from food we paid for), kept our place clean, and did our laundry. It cost each of us five dollars a month.

The other room was occupied by Elders Law and Blank. One of their investigators was a dowager-type woman who occasionally invited them to lunch. Elder Law, who spoke better French, usually blessed the food, and when he did so he also blessed the woman for her generosity.

In the middle of one of Law’s blessings the slightly eccentric lady blurted, “Don’t forget me.”

One day in the bright spring of 1949, she invited all four of us to lunch. She wanted us to be impressed and entertained by her fifth guest.

That guest: Dr. Edmond Locard!

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |