| Print | Back |  |

January 13, 2014 |

|

Moments in Art Folk Paintings, a Varied Bouquet, Part 2by Lawrence Jeppson |

One artist painted with his fingers because “they never wore out.” One decorated every surface of his home except the floors. One was named after a sewing machine. One envisioned himself being constricted by the serpent from the Garden of Eden, who was his gleeful former wife.

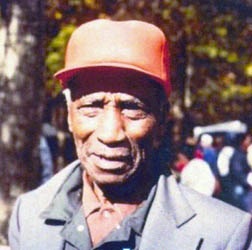

Jimmie Lee Sudduth (1911-2007) “was a prominent outsider artist and blues musician from Fayette, Alabama” (Wikipedia).

Raised on a farm at Caines Ridge, Sudduth “began making art as a child, surrounding the porch of his parents’ house with hand-carved wooden dolls and drawing in the dirt or on tree trunks outside. As his talents became known in the community he began collecting pigments from clay, earth, rocks, and plants for use in his finger paintings. He used his fingers because ‘they never wore out.’

Wikipedia adds that Sudduth’s “numerous works were typically executed on found surfaces such as plywood, doors, and boards from demolished buildings. He experimented with mixing his pigments with various binders to make them adhere better, including sugar, soft drinks, instant coffee, and caulk.” (Ibid)

Even so, many of his earlier works used house paint. Like many African Americans in the South, he lived on poor side of the railway tracks, and the more prosperous Whites lived on the other. He did work as a gardener for one of the latter, the Moore family, who quietly supported him in his artistic efforts. So did Suddoth’s next-door neighbor, Jack Black, who was committed to Alabama art.

Jimmy Lee was 58 when he had his first public art exhibition, at Stillman College in Tuscaloosa. Other recognitions followed, including appearances on The Today Show and Sixty Minutes. He painted almost no religious subjects.

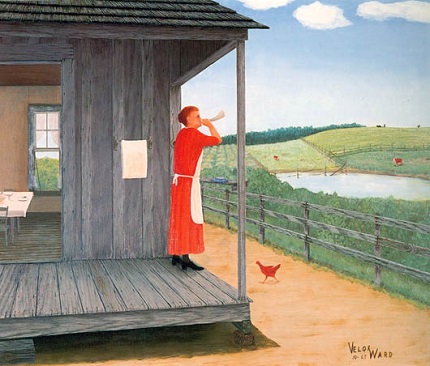

Velox Ward (1901-1994) was born in East Texas and was named after a German sewing machine.

Ward was in the seventh grade when his father died. “I worked at any job that would keep my head above water: farmhand, machinist, foundry worker, garage mechanic, salesman, plumber, wrestler, and shoe repairman.” (Quoted by Chuck and Jan Rosenak.)

Ward was nearly sixty when he began to paint. His three children asked him to paint pictures for their Christmas presents. His life output would reach 200 paintings. Although he worked in his own shoe repair shop, his realistic scenes often recalled earlier farm life: putting up hay, butchering hogs, ginning cotton, calling people to dinner.

His interpretations of farm life were realistic rather than fanciful, and in time he was recognized by prestigious institutions such as the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth.

A room created by folk artist Joseph Endicott Furey brings to mind a more sophisticated room in the sometimes-overlooked treasure on the Washington Mall, the Freer Gallery. The Freer is one of the great museums of Oriental (Asiatic) art, yet one of its most spectacular treasures is Whistler’s Harmony in Blue and Gold, the Peacock Room.

James Abbott McNeil Whistler (1834-1903) was commissioned by Frederick Leland to decorate a large room in his house. When Leland saw the finished room, he was so displeased that he and Whistler nearly came to blows. After Leland died, Freer purchased the room from his heirs and painstakingly reconstructed it in his new museum.

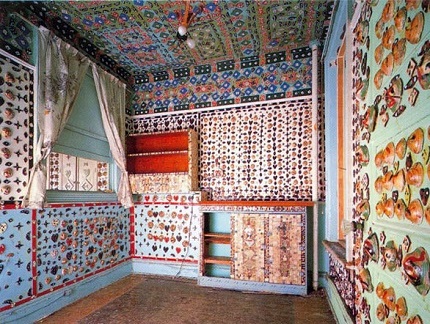

Furey (1906-1900) left his Boston home at 13, worked picking fruit and doing odd jobs, enlisted in the Navy at 17, became the light heavyweight boxing champion of the Pacific fleet, became an up-high steel worker on structures such as the Golden Gate Bridge, the Washington Bridge, and an oil refinery in Venezuela.

In 1938, he rented a five-room apartment in Brooklyn and lived there for 50 years. He began decorating its bathroom. After his wife died, he turned to decorating the entire apartment. He was 75.

“Furey developed an abstract series of mosaics, tied together with a bow-tie motif. . . He covered virtually every inch of the walls, ceilings, and much of the furniture with geometrical patterns. The entire apartment became one single, shimmering, balanced, and symmetrical work of art.” (Rosenaks)

Furey used some 70,000 items glued or nailed down: shells, dried lima beans, bow ties and hearts cut out of cardboard, plaster chickens, and anything else that caught his fancy. He covered everything with a clear coat of polyurethane varnish.

When Furey moved out, his landlord faced a quandry: what to do? He called the Brooklyn Museum curators. They called the Museum of American Folk Art. As the Rosenaks observed, “Furey turned his apartment into a spectacular personalized environment without realizing he had created one of the most important conceptual sculptures of our time.”

The landlord rented the place to two photographers, who maintained its integrity as live-in caretakers for four years. New owners took over the building, and the photographers moved out. Two days later, the new owners gutted the apartment. Only the photographic record remains.

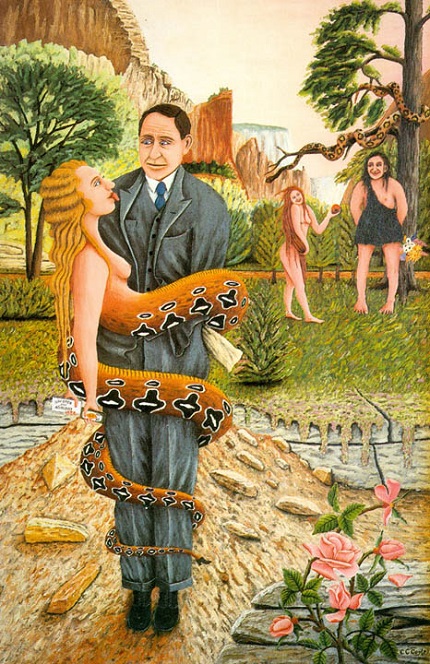

Carlos Cortez Coyle (1871-1962) was a self-taught painter who grew up in Dreyfus, Kentucky. At 18, he briefly attended Berea Foundation School (a high school) run by Berea College, where he was introduced to Appalachian arts and crafts. He left school early, moved to Florida, moved to Canada, failed in an attempt to make a living at farming, took up work in the building trades.

He moved to San Francisco after World War I, but his employment ran out with the Great Depression. He worked in lumberyards and shipyards. He married, had two sons, divorced.

In 1929, at 60, he began painting, evidently when his mother died.

In December, 1942, Berea College received four large crates. The crates were not opened until they were discovered by an art curator in 1960!

The crates contained 47 paintings, 37 drawings, a diary, and a letter saying the shipment was a “gift to the land of my birth.”

Coyle’s “known work consists of landscapes, paintings of women, both clothed and unclothed, and celebrations of heroes and scientific progress. All record his unique personal philosophy — a mixture of patriotism, love of the countryside, and a complicated love/trust/hate relationship between himself and his mother and former wife — in an unusual surrealistic and semi-allegorical style.” (Rosenaks)

In the painting shown below, The Transformation, Coyle transforms the Garden of Eden. It depicts the artist with his former wife, who takes the form of a serpent coiled around his body.

| Copyright © 2025 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |