| Print | Back |  |

December 9, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art The Folk Art That Many Folk Getby Lawrence Jeppson |

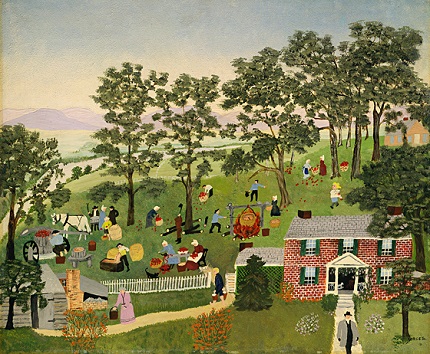

The most famous American “primitive” painter of the 20th century was Grandma Moses (1860-1961).

“Primitive” means without formal art training. “Folk art” is often preferred to describe this kind of art. The French employ the term naïf, meaning naive.

Anna Mary Robertson did not start out to be an artist. She was one of ten children born to a family in Greenwich, Connecticut. What little schooling she received was in a one-room schoolhouse. She left home at 14 to work as a domestic servant and was so employed when, at 27, she married Thomas Solomon Moses, a hired man on the farm where she worked.

They went on a honeymoon to North Carolina and on the way back decided to rent a farm near Staunton, Virginia. In the next 20 years in Virginia she gave birth to ten children, half of whom died in infancy. She made and sold butter and potato chips to neighbors.

They moved to a farm in Eagle Bridge, New York, where her husband died in 1927. She was 67. When arthritis became crippling to her hands, she had to give up farm work. She began embroidering wool pictures based upon Currier and Ives prints. When she could no longer handle a needle, she took up a paintbrush and produced her first paintings. She was 76.

Although her first efforts were copies of prints and postcards, she soon summoned her farm-life memories and began creating her own depictions of those days, events, and places.

In 1936, collector Louis Caldor was driving through Hoosick Falls, New York. He saw some paintings displayed in a drugstore window. They were priced $3 and $5 (up a bit from the $2 and $3 the artist had been charging). He bought them all, then went to find the artist and purchased 10 more.

The next year the Museum of Modern Art, New York City, included three Moses paintings in “Contemporary Unknown American Painters.” Moses’s career as a painter was off and running.

When the press began calling her Grandma Moses, the name stuck.

Using rural settings, her paintings celebrated all the holidays. By the 1950s, her exhibitions were so popular they repeatedly broke attendance records. Her viewers were not out seeking “great” art; they were reliving with her the simple joys of times and places that were either disappearing or nearly forgotten.

She sometimes thought her preserves were more important than her paintings. But her art was popping up on cookie jars, aprons, dinnerware, wearing apparel, and product advertising.

She had become internationally famous and loved.

Honors were heaped upon her. In 1950, the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., named her as one of the five most newsworthy women in the world. Mademoiselle extolled her as “Young Woman of the Year.” She received honorary doctorates. Governor Rockefeller proclaimed her 100th birthday “Grandma Moses Day.”

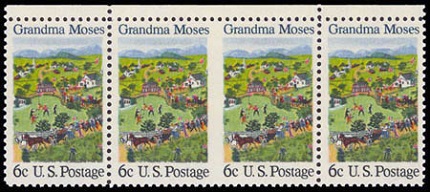

A 1969 6¢ United States postage stamp posthumously depicted one of her folk paintings.

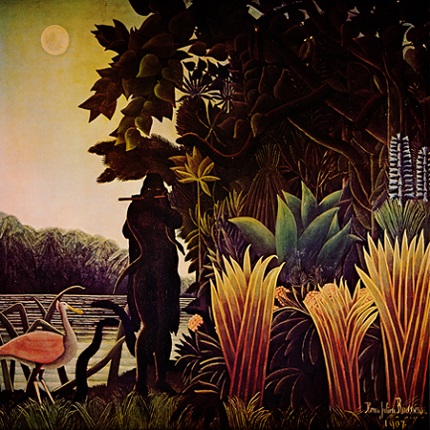

On the other side of the Atlantic and more than a generation earlier, the most famous of French naîfs was Henri Rousseau (1844-1910), also known as Le Douanier / The Customs Officer because he worked as a toll collector.

Unlike Grandma Moses, he was ridiculed during his lifetime. Eventually, as his work began to be appreciated, he sometimes was lumped with the Post-impressionists because there was no place else to lump him that carried the right prestige.

Born in Laval, France, he was forced as a boy to work for his father, a plumber. The family left town when the father lost their home in a debtor foreclosure. Although Henri could draw, he did poorly in school. He worked for a lawyer until he had some troubles and fled into the French army for four years.

He moved to Paris to support his windowed mother, married his landlord’s 15-year-old niece, fathered six children (only one survived), and secured government employment as a collector of city tolls on good brought into Paris.

About 1885, he began painting seriously. The National Gallery in Prague owns a self-portrait painted in 1890. It shows him standing starkly on a dock, wearing a dark suit and an excessively floppy Basque beret, and holding a paintbrush and palette. The single-masted canal sailing ship displays a collection of bright flags. This may have been the beginning of a style he claimed he invented.

When Rousseau was 49 (1893), he retired from his bread-and-butter job so he could paint full-time. He was self-taught. He is quoted as saying, “I hate books. They only teach us to talk about things we know nothing about.”

Far from usual 20th-Century techniques, Philippe Bonamy (born 1926, Nanttes, France) is a resolutely figurative primitive. He is not a naive primitive like Grandma Moses or Henri Rousseau. Although he has the meticulous attention to detail and some of the style of the Renaissance — e.g. the use of landscape backgrounds for portraits — he insinuates them with unexpected tricks of a surrealistic nature that have brought him fame.

His Paris dealer, Suillerot, said to me, “He’s a naif, but he knows exactly what he is doing.” I first encountered Bonamy’s paintings in a fine art gallery in the huge Marshall Field department store in Chicago before I began circulating collections of French artists.

As Suillerot said, you always feel that Bonamy knows exactly what he is doing. He leaves you feeling as comfortable as you do when viewing an old master, but then something in the detail disturbs you, like the bite of satire or the juxtapositions of the Surrealist.

Here are three of the five Bonamys from my collection:

| Copyright © 2025 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |