| Print | Back |  |

November 4, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art The Impressionist Who Saved the Impressionistsby Lawrence Jeppson |

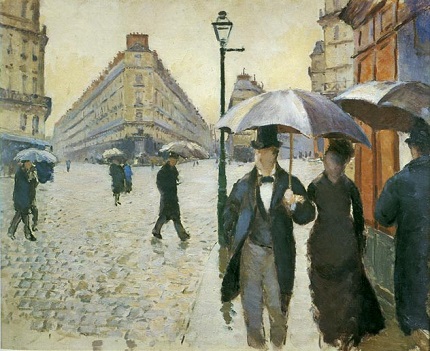

Of all the paintings I have ever seen, if I could have just one for the rest of my life, it would be Rue de Paris, Temps de Pluie/Paris Street, Rainy Day by Gustave Caillebotte.

Perhaps because I look at Paris as my second home.

This hauntingly beautiful cityscape by Caillebotte (1848-1894) belongs to the Chicago Art Institute, where I have admired it several times and probably never again will see it. I saw it last when it was borrowed for an impressive Caillebotte retrospective by the National Gallery, Washington, D.C.

No reproduction, with the possible exception of a full-scale computer generated giclée, can ever do justice to the subtle complexity of this evocative masterwork. So what you see with this column can be only a weak hint.

(I make that theoretical exception because several years ago I saw the trial proof of an 86% size giclée of Arnold Friberg’s iconic Prayer at Valley Forge, side by side with the original, and even at that first stage, they were virtually identical.)

Caillebotte finished Paris Street, Rainy Day when he was only 29. Like Katharine Lane Weems, whom I wrote about last week, he was born into a rich family and was not dependent upon his art for his livelihood. In fact, just five years later he quit showing his work.

Gustave’s grandfather grew his fortune making military uniforms for the Second Empire armies of Napoleon III. His father enlarged the family wealth and served as a judge. The father was widowed twice before marrying a third time and having three more sons, Gustave, René (who died at 25), and Martial. Martial, like Gustave, did not need to work in usual pursuits and spent his life writing music. The two brothers were close.

Gustave took a degree in law (1868) and obtained his lawyer’s license two years later. He was also an engineer, excellent yachtsman, avid gardener — and, of course, a painter. Both sons were passionate philatelists, and their stamp collections ultimately were acquired by the British Museum, London.

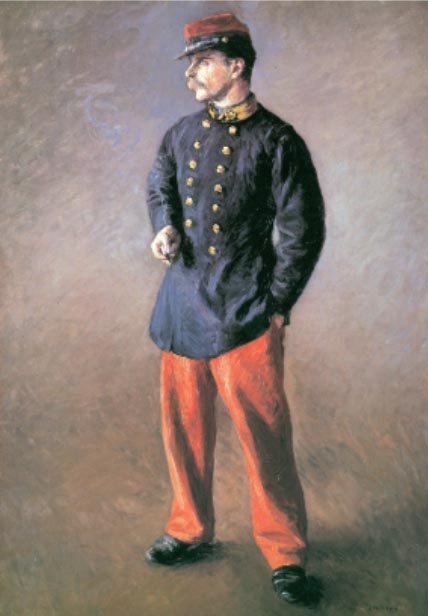

He was conscripted for service into the Garde Nationale Mobile de la Seine during the Franco-Prussian War. The Garde became the military wing of an uprising, the Commune, against the French government that had started and lost the war with the Germans. This brought an end to the Second Empire, and before the Commune took control of Paris, Gustave was ready to be a civilian again and pursue an artistic career. He was 22.

The switch must have been difficult and threatening. Agitating for radical social changes, the Commune was supported by the working class, women as well as men. In the Bloody Week, government forces from Versailles stormed Paris, fought in the streets, and defeated the disorganized Commune. Terrifying reprisals followed for anyone associated with the Commune. Karl Marx, from afar, shed tears.

Caillebotte began studying in the studio of Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), an academic portraitist. Another Bonnat student was Edgar Degas, who mentioned Gustave in an 1871 notebook. Degas would introduce him to his Impressionist friends.

When he went with his father the next year to Italy, Gustave was struck by the difference in light (as was Corot a generation earlier) and painted some of his first landscapes. Gustave, 25, was admitted to the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-arts, but he seldom attended classes.

And then, another year later on Christmas day, Gustave’s father died. He left his sons with a “belle fortune.” Older half-brother Alfred, an ordained priest, left with 50,000 pounds income, became “the richest curé in Paris.” Gustave and his younger brother Martial inherited most of the patrimony and could devote the rest of their lives to art (Gustave) and music (Martial).

It is incredible that only four years after beginning, though seldom attending, the Ecole des Beaux-arts Gustave was able to paint Paris Street, Rainy Day!

Recognition in France was controlled by the hostile academic juries of the Paris Salon. In the spring of 1874, the group of artists who soon would be called, derisively, Impressionists held their first exhibition, hoping to be recognized by the public.

Claude Monet recalled six years later, “For some time my friends and I had been systematically refused by the jury. What to do? It was not enough to paint. We had to live.” (Marie-Josèphe de Balanda, Gustave Caillebotte, La Vie, La Technique, Lœuvre Peint , Lausanne, 1988)

Although Degas thought Caillebotte would be one of the exhibitors, he was not. He was there as a supporter. In future manifestations, his paintings would be included.

The next year work by Caillebotte, looked upon as an amateur, would be among the 73 canvases by Berthe Morisot, Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and others put on the Hôtel Drouot auction block. The sale was a disaster! Caillebotte was the high bidder — at very low prices — for some of the paintings, as he sought to support his friends.

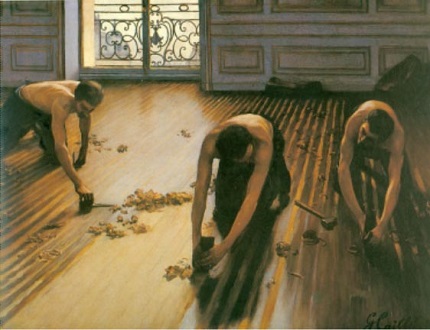

A few months later the Salon rejected one of Caillebotte’s own paintings, thought to be Les Raboteurs de Parquet/The Floor Scrapers, now recognized as one of the artist’s most powerful works. This was the final straw that turned the artist against the Salon. He received a new invitation from Renoir: “We would be very happy to see you associated with us in this new try.”

Caillebotte participated in the second Impressionist show with eight canvases, including two versions of The Floor Scrapers.

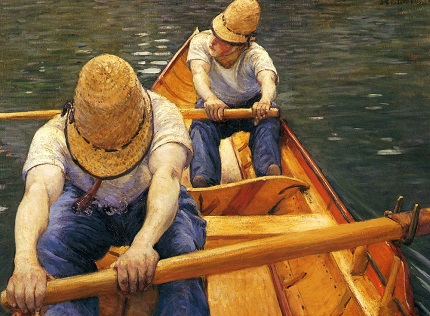

Earlier in the 19th century when Academism held even a more vice-like grip on the canons of art, Millet had dared to break away from classical stuff and glorify peasants at work. The portrayal of rural rustics became acceptable. The Salon crowd looked upon Caillebotte’s realistic painting of urban workers as vulgar.

Although his realist paintings did not employ the divisionist techniques being discovered by Caillebotte’s friends, he was justifiably considered an Impressionist, as much of his other work testifies.

When Gustave’s brother René died in 1876, Gustave became convinced that members of his family died young, and he drew up a will naming “the stubborn ones” as his beneficiaries. Renoir was named his executor.

The next year Gustave procured an apartment for Monet for which he paid the rent of 175 francs every trimester.

To enable the Impressionists to have their third exhibition, Caillebotte rented an appropriate space and then helped Renoir, Monet, and Pissarro hang the show. A critic saluted this “organizer without equal, always ready to rent halls, organize expositions, pay rents, and unceasingly give himself and his wealth.” (ibid)

This third show marked the high watermark of Impressionist manifestations. Monet was adamant that no Impressionist who submitted to the Salon should be allowed to participate. Some of the lesser painters from the first two shows were excluded, and some of the greatest works by the participating artists were included. Caillebotte was represented by six canvases. One of them was Paris Street, Rainy Day.

Emile Zola, who had greeted prior Impressionist shows with enmity, changed horses. His approval signaled out Caillebotte.

The painters decided again, 1877, to try to sell at auction at the Hôtel Drouot. The highest price realized was 655 francs for Gustave’s The Floor Scrapers. To help his friends, Caillebotte kept bidding up their prices.

Caillebotte moved Monet into a better studio and paid for it himself. Then he financed the fourth exposition, which Degas titled “Exposition of a Group of Independent Artists.” Cézanne, Sisley, and Renoir decided they’d take their chances at the more prestigious Salon. Morisot was pregnant. Monet was ill, and only the intervention of Caillebotte with 2,500 francs enabled him to repair and ship two paintings. Caillebotte himself was represented by 25 works — landscapes, portraits, pastels.

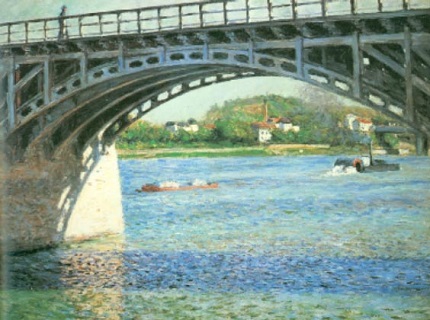

Caillebotte ceased showing his work in 1882, when he was only 34. He devoted himself to designing and racing yachts and spent a great deal of time with his brother Martial and with Renoir. He and Renoir were avid gardeners.

He died of a pulmonary embolism at 45. The disposition of his estate — his fabulous collection of art by his friends — is another compelling story.

His support of his Impressionist friends was so legendary that this was the only part of his career that drew much attention for the next 82 years! I had never heard of him until I came across his great painting in Chicago, and I began challenging my friends to identify Caillebotte. This neglected master became one of my favorite painters.

Only when his family — he never married and had no direct heirs — began selling his paintings did the world start to take notice. When the Art Institute of Chicago acquired Paris Street, Rainy Day in 1964, Americans began to wake up.

| Copyright © 2025 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |