| Print | Back |  |

October 21, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art The Smart Imbecileby Lawrence Jeppson |

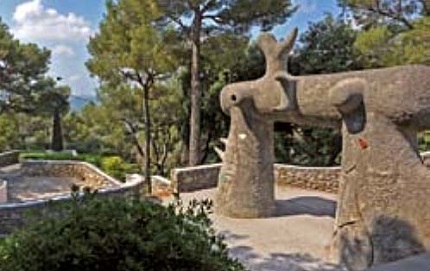

The south of France is littered with one-man museums and art foundations. None is more opulent, extensive, and beyond the expected than the Foundation Maeght at Saint-Paul-de-Vence.

Artists have flocked to the Côte d'Azur for more than a century, sometimes painting a few pieces while lingering briefly, sometimes staying for the balance of their lives. A few months before his death, Fernand Léger (1881-1955) bought a farmhouse at the foot of the village of Biot. There his widow and a friend decided to build a museum honoring (promoting) the famous painter and his work.

They built a very modern structure whose dimensions were determined by a huge mosaic Léger had designed for the Hanover Stadium in Germany but never realized. The colorful outside mosaic covers the museum's front wall.

This was the first of the one-man museums in the region. Accompanied by Maurice Perrier (see Moments in Art #6, “Hammer and Fire”), I saw the museum shortly after it opened and was pleasurably impressed. Today there are one-man museums along the coast, for Matisse, Picasso (at least two of them), Chagall, Bonnard, Renoir, and Cocteau.

These have stimulated a substantial flow of 20th Century art to other Midi museums and foundations. But nothing matches the Maeght, not in quality, not in quantity, not in breadth, and not in the beauty of its campus.

Aimé Maeght (1906-1981) and his wife Marguerite built their art-dealing empire from a Right Bank gallery at 13 Rue de Téhéran in Paris. They began with two already-great artists in their fold: Pierre Bonnard (1869-1947) and Henri Matisse (1869-1964). They soon added Braque, Chagall, Kandinsky, Miro, Calder, Giacometti, Tal-Coat, Riopelle, and a bunch of others. The Maeghts were not just exhibitors, they created a machine.

In an article in Cimaise magazine, 1967, Yves Taillander recounts a story from the Sixth International Exhibition of Surrealism held in the gallery two years after it opened.

The universal museum mantra is, “Don’t touch.” In several museums I’ve caused very loud alarms to reverberate when I got too close to something, without even touching. Surrealist artist Marcel Duchamp persuaded Maeght to post a sign for the public, “Please Touch.”

Reversing the idea, Maeght (pronounced mahg) knew the gallery had to reach out and touch the public. The Maeght machine grew to include, among others, a press secretary, three regular secretaries, two full-time photographers, five bookkeepers, two librarians, two researchers, five shippers, two billing clerks, three designers, four framers, and 40 employees in a print shop producing engravings, lithographs, photographs, and offset printing.

I worked closely with four different dealers in Paris, two on the Right Bank, two on the Left. They were good merchants, honest and dedicated, representing good artists, but none of them had the capital and clout of Maeght.

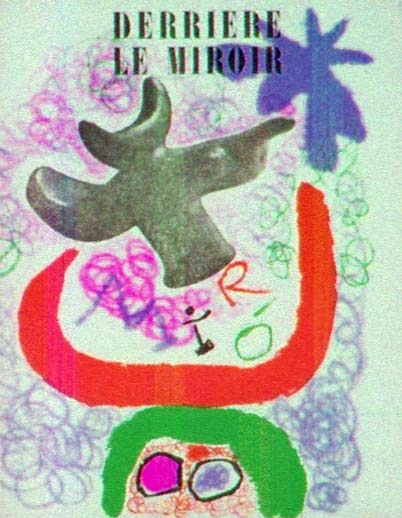

When I interviewed Maeght in Paris for a proposed book Merchant Oracles of Art, the company had added a Left Bank gallery on Rue du Bac (still in the family) and a gallery in Barcelona. They were publishing an impressive review called Derrière le Miroir (Behind the Looking Glass). The title derived from Alice in Wonderland. Each issue dealt only with Maeght artists and often was illustrated by original lithographs.

Derrière le Miroir ceased publication in 1982, with issue number 253. I wish I had purchased some of them as they were issued. In the aftermarket, titles now sell from $100 to $750. My interview did put me on Maeght's mailing list, which brought show announcements and original lithoed Christmas cards designed by their artists. I have saved them.

In 1953, Aimé and Marguerite, depressed by the loss of their youngest son to leukemia, took the advice of Léger and made a trip to America, where they studied the Barnes, Phillips, and Guggenheim foundations and their museums. A museum of modern art had not been built in France since 1936.

They began planning their foundation campus near Nice. They expected to build it in stages taking ten years; it was finished in four. In 1964, the red ribbon for its opening was cut by André Malraux, one of France's most famous writers and the French Minister of Cultural Affairs. Ella Fitzgerald and Yves Montand sang to a distinguished gathering.

Malraux said, “Here you have tried something that has never been attempted before, to create a universe in which modern art can find its own place… The result belongs to posterity.”

The annual attendance has been 200,000 visitors.

How did all this start? It’s a Horatio Alger story.

Aimé Maeght was born in the North near Lille, and I suspect the name might have Flemish origin, as many do in that part of France. He moved to warmer climes, Cannes in the south. By trade, young Maeght was a lithographer. In 1930, Bonnard came into the workshop and asked Aimé to print a program for a Maurice Chevalier concert using a Bonnard lithograph.

In 1936, he and his diminutive, highly energetic, and pragmatic wife decided to open a little shop in Cannes. They called it, simply, Arte.

There is some confusion as to when the following incident took place. One account says 1930, another 1936 after the shop opened.

There was a Bonnard in the workshop, which Aimé had been asked to reproduce. Marguerite hung it in the shop. An elegant man entered, asked if it were for sale and at what price. She was surprised and uncertain. So she proffered a very high price. It was accepted. Chagrined, she went to Bonnard to confess. Bonnard replied, “That's a very good price. If you want more paintings, take them. I’ll give you a percentage.”

The next day she showed up at Bonnard's with a wheelbarrow!

When Word War II erupted, Marguerite was forced to sell furniture, bric-a-brac, and whatever she could scrounge. The art dealer-lithographer, aligned with the Resistance, printed false identity cards, bread ration coupons, other documents. Suspected, he went into hiding not far from where Matisse lived.

The war over, Bonnard, Matisse, and the Maeghts, representing the artists in their small gallery, became close friends. Marguerite posed for numerous portraits. They loved to tease each other. Talking about a painting with an open window, Bonnard boasted, “I beat you to that.” Matisse replied, “But I did it better.”

There is one more kicker to this story.

The two painters and Maeght decided that Maeght needed to open a gallery in Paris. The three of them went off to the capital to search for a location. It was not easy to find any place in Paris after the war. Rent control strictures dating back to the post-war period of World War I were still in place.

New buildings were not being built, and the value of the franc had repeatedly plummeted. Rents that could be charged were almost nothing. Canny Paris real estate owners got around this in ingenious fashions.

“I can only charge you this little monthly rent. However, to get in you will need to buy this key to the property for [some very high figure].”

The searchers found a place, 13 rue de Téhéran, whose owner did not appreciate its potential. He complained he would sell, “if he only knew the imbecile who would buy it.”

“He's right here,” Bonnard answered. He pointed to Maeght.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |