| Print | Back |  |

September 9, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art Fatal Auto Crash's Not-So-Cruel Consequencesby Lawrence Jeppson |

For the second time in these “Moments in Art,” the crux of my tale recounts the consequences of a calamitous crash of an automobile and a truck.

The first was in my May 13 column, “Where’s the Beef,” which began with the fatal 1951 Philadelphia crash between a heavy truck and a car driven through a red light at 120 mph by Dr. Albert C. Barnes, age 79, an eccentric art collector.

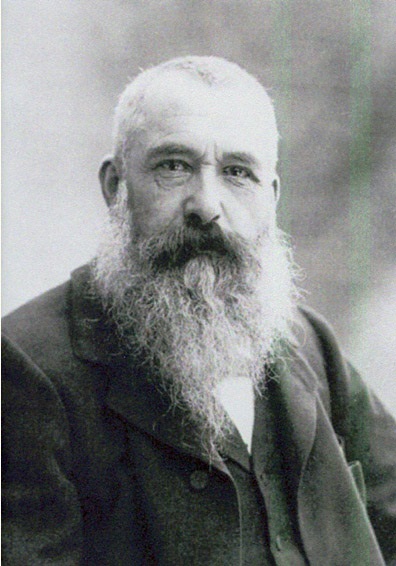

In 1966, Michel Monet, the son of Claude Monet, the towering French Impressionist, plowed into a truck and was killed. He was driving back from visiting his wife’s grave in Normandy. Michel was the inheritor of his father’s paintings and sketches, which he kept for forty years stashed under beds and stacked in closets gathering dust in a country house in Normandy, far from the eyes of Paris.

Michel inherited other art that Claude had not painted, including works by his father’s masters Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) and Eugène Boudin (1824-1898), and paintings by his fellow Impressionists. (Artists sometimes trade works.)

Michel bequeathed his father’s property in Giverny, the most glorious few acres in French art places, to the French Académie des Beaux-Arts, a learned society created in 1816 and limited to 60 living painters, sculptors, architects, photographers, and a few unattached members. (Very few get in.)

Although Claude Monet was famous and rich in his lifetime, he was miffed that the Louvre never recognized him, never gave him a show. He forbad that any of his legacy be given to the French State.

Today, a French artist of such stature could never get away with this. The government would swoop down on the estate and take a generous part as payment for death taxes. The government did that after Picasso died, which is why there is a notable state-owned Picasso museum in Paris.

Obeying his father’s wishes, Michel left more than 130 paintings, watercolors, pastels, and drawings to an obscure Paris museum on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne in the tony 16th Arrondissement. The Marmottan Museum owned a collection of First Empire era antiques, Renaissance tapestries, and countless miniatures.

Even though it already possessed several Monet paintings, including the historically important Impression Sunrise (1872), which lead a newspaper critic to dub the new movement “Impressionism,” it was virtually unknown to the art world — and certainly unknown to the outside world.

It did not seem an appropriate repository for such an awesome collection.

Though not visible, the bequest was the largest collection of Monet’s art in the world, and it covered his career. Eventually the museum would be renamed the Marmottan-Monet.

How could such a small museum accommodate such a large bequest and the notoriety the collection would bring?

Inevitably, the presence of such a monumental collection would attract other significant donations of other groups of art seeking permanent domicile.

Where would it all go?

Many years before any of the Monets, the Duke of Valmy built a hunting lodge on the land. In 1882, Jules Marmottan bought it. His son, Paul, took it over and built a new hunting lodge big enough to house his collection of Third Empire paintings and other objects.

In the Paris context, a hunting lodge is not a cabin in the woods. This one was a large two-story stone residence, plus an attic third story of the kind where servants and shoestring relatives live. Although there was a large garden in the rear, there was no way, left or right, to expand the house, which was already chock-a-block with family collections when Monsieur Marmottan converted it to a museum in 1934.

Where would the Monet collection go? What a terrible dilemma!

The Marmottan directors set a precedent that the Smithsonian Institution would follow several decades later when confronted with the necessity to build two new museums on the Washington Mall between the original display building and the Freer Gallery. Go deep.

Marmottan architects began by removing the lovely garden in the back yard. Then they excavated. In the hole they built and lighted new exhibition rooms, all below ground. Then they put the grass back, on top of the expanded facilities.

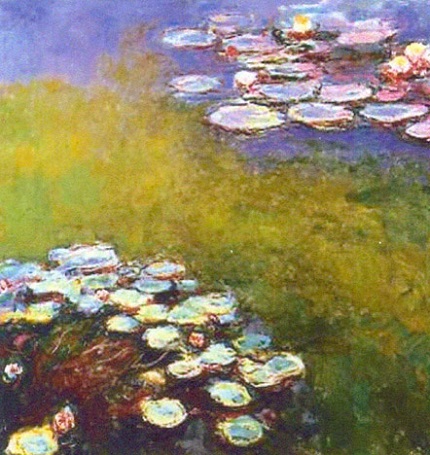

Michel Monet’s bequest is magnificently displayed. It traces Claude Monet’s career, from early to late, with stunning examples of his work. Nowhere in the world can a gallery goer get a better display of the artist’s whole career.

The original Marmottan collections are still there, in the old house, but the museum has become the home of other notable collections. To keep the spirit of the museum crackling, temporary exhibitions are occasionally mounted. From October 3 to January 26, 2014 it will exhibit Soeurs de Napoleon/Sisters of Napoleon. (The museum will be closed from September 23 to October 2 for the installation.)

And sometimes the Marmottan lends its art to other institutions, and a visitor may be disappointed to discover that important paintings are not on display. At the moment, 60 Monet paintings from the Marmottan are hanging in an exhibition extolling Monet’s Garden at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia. It runs there through September 8, 2013.

Whenever I learn of friends going to Paris for more than a day or two, I recommend they seek out this gem of a museum.

The Marmottan-Monet is off the Paris beaten path. But the Metro stop La Muette is nearby. This is one case where underground art, to use a Michelin guidebook term, is “worth the voyage.”

| Copyright © 2025 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |