| Print | Back |  |

August 12, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art The Mormon Epic on a Rollby Lawrence Jeppson |

No article in any art periodical ever astonished me as much as one that appeared in the May-June issue of Art in America 33 years ago. Usually any art magazine spread would top out at about half a dozen pages. This one was 34 pages long, mostly given to illustrations.

The unprecedented length was not the only thing that made be bug-eyed. More astonishing was the title, “A Panorama of Mormon Life,” and the illustrations that followed.

The article touted the paintings as one of the great discoveries of 19th-century art, big canvases created by a totally unknown frontier artist. The extraordinary article appeared in conjunction with the exhibition of the paintings at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, the most prestigious venue where they could have appeared.

The unrecognized artist was Carl Christian Anton Christensen (1831-1912).

Cultural historian Carl Carmer brought the panorama to the attention of the American art community through the Whitney, American Heritage, and Art in America.

Christensen was born into an impoverished family in Copenhagen. He had younger brothers. His mother taught him how to amuse himself by using scissors and paper to make playthings. Though the youngest in his school class, he was its top student. He was 11 when his mother, inspired by a dream, placed him in an orphanage run by the state for the benefit of poor families.

The orphanage ran like a military academy, with hymns, prayers, and meals on a regimented basis, along with academic studies and training as artisans or craftsmen. Because of what his mother taught him, he became a toymaker. His life took a turn when Christmas silhouettes he cut out of paper were seen by three women. They offered to finance his training at the Royal Academy of Art.

At 14, he was discharged from the orphanage and apprenticed to a carpenter. One of the women offered to compensate the master for the two hours Christensen would spend each evening at the Academy, where he began at the elementary level. The Academy curricula were based entirely on drawing.

With the aid of benefactors he was able to transfer his apprenticeship from the carpenter to a master painter, with whom he could take his artistic training to a higher level. But the new master was mainly a decorative painter, and he taught his student easel painting and house painting, skills that would be important in Carl’s later life.

In 1850, Carl’s mother became one of Denmark’s first converts to the Mormon church. Carl’s and two of his brothers’ conversions soon followed. As his religious zeal gained momentum, his artistic dreams began to dim. He hoped to advance from the second freehand class at the Academy to model school, where students could sketch from live models. He could not gain promotion.

“Because of this, his art would show skill in composition and in the use of perspective, but a delightfully naive awkwardness portraying the human form. For many twentieth century viewers this peculiar mix of skill and naiveté makes his work a disarmingly straightforward and visually effective statement.” (Exhibit catalog, Museum of Church History and Art, Salt Lake City, 1984)

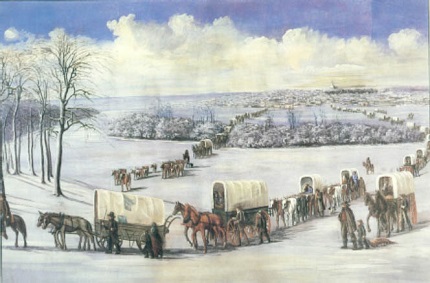

Seven years would pass before Carl and his new bride, Elise Scheel Haarby, a Norwegian fellow emigrant he would marry en route in Liverpool, would follow other Scandinavians to Utah. The last leg of their honeymoon was to drag a handcart from Iowa City, Iowa to Salt Lake City, which took nearly three months.

The group numbered 68 handcarts, 3 wagons, 10 mules, and a cow that died. As company clerk he kept a daily record. Although he spoke respectable English, he composed songs en route in Danish, including a handcart song.

It was a hard trip, pulling everything one owned and needed along the way, a cargo limited to 17 pounds of luggage (later reduced to 15). Sometimes getting water was a problem. People died.

There was fun and adventure along with the toil. A 60-year-old blind woman made the entire trek, as did a girl with a wooden leg. Hunters looked for game to supplement their rations. One man who had no sense of smell returned to camp with a skunk he had bagged. This was not warmly received.

When Carl and his wife arrived in Salt Lake, his pants were in tatters, but the Danish flag flew from the handcart.

Life as a frontier artist was not easy. He painted stage settings and houses and received commissions to paint scenes from the Bible and the Book of Mormon. His output of paintings was prodigious, yet he homesteaded three times, taught drawing and Danish, wrote extensively about art history, theology, and rural life, and painted Manti and St. George temple murals.

Feeling divinely inspired, in 1878 Christensen began painting the Mormon Epic, chapter by chapter, from Joseph Smith’s first vision to the arrival of Brigham Young and in Zion.

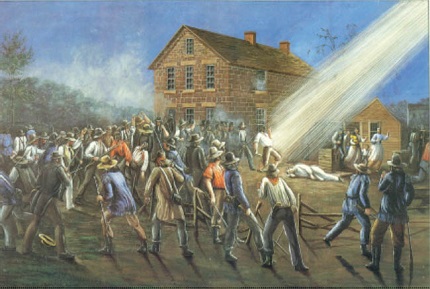

The Mormon Panorama would become 23 large paintings on canvas. He stitched them together end to end, chronologically, creating a roll 175 feet long. He began touring communities in Utah, Idaho, Arizona, and Wyoming giving lectures on Mormon church history as the large scroll was unwound, scene by scene.

Christensen wrote, “The old generation which bore the burdens of the day in the persecutions in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois will no longer be with us a few years hence. History will preserve much, but art alone can make the narrative of the suffering of the Saints comprehensible for posterity.”

Eventually the long roll was retired, laid away, and forgotten for decades. These are the paintings discovered and exhibited with such eclat at the Whitney Museum in 1980, and featured in such extravagant fashion in Art in America.

The rediscovery began with LDS Apostle Boyd K. Packer. In a speech given at Brigham Young University in 1976, he said, “Several years ago I was chairman of a committee of seminary men responsible to produce a filmstrip of Church history.

One of the group, Trevor Christensen, remembered that down in Sanpete County was a large canvas roll of paintings. They had been painted by one of his progenitors, C. C. A. Christensen, who traveled through the settlements giving a lecture on Church history as each painting was enrolled and displayed in lamplight. The roll of paintings had been stored away for generations. We sent a truck for them, and I shall not forget the day we unrolled it.”

Eventually the paintings became the property of Brigham Young University.

Why did it take C. C. A. Christensen seven years after his conversion to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to hie off to Utah? Most converts, reacting to the summons to gather in Zion, departed as soon after baptism as they could. He was deeply committed to the Church and kept answering Scandinavian mission calls.

At various times he spent three and a half years as missionary and mission president in Norway. Preaching Mormonism in Norway was against the law, and he was twice put in prison.

As nearly as we can establish, Christensen had a hand in teaching and converting Gunnell Marie Hansen, who emigrated with 383 other Scandinavian Saints on the Benjamin Adams in 1854. She was the daughter of a deceased sea captain and made the trip with her mother and two brothers, who did not want her traveling alone. The mother and one brother would be buried in unmarked graves in Nebraska. I have been told that until then the Scandinavian emigrants left in bits and drabs but the Benjamin Adams was the first ship hired to bring a big group of Nordic Saints.

On the voyage she met a young Swede who was kept busy as an interpreter because he spoke four languages. She saved his life during a river crossing accident in Wyoming. They married a few days after their arrival in Salt Lake City and soon after were sent with 49 other families to establish Brigham City.

Thank you, C. C. A., for your Norwegian missionary labors. Gunnell was my great-grandmother.

The young Swede was Jeppa Hans Jeppson, my great-grandfather.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |