| Print | Back |  |

August 5, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art Not the Flame that Burned Withinby Lawrence Jeppson |

Through plunder, avarice, and catastrophe, great treasures of art have been lost in wars, but the greatest enemy to art is fire.

Painter John O’Shea (see column) and his wife Molly abandoned their home in Carmel Highlands and moved a few miles north to the ritzier Pebble Beach. The paintings he sent back to New York were bringing as much as $3,000.

O’Shea was a “distinguished member” and director of the Carmel Art Association. He became its president and a guiding force. When the association moved to new quarters in 1934, John and Molly landscaped and personally planted the grounds.

After Molly died of cancer, John moved into Carmel itself, where he lived, some say, almost as a recluse — often dark and uncongenial — until his death in 1956. The truth is, he was often visited by artists and girlfriends, and neighborhood children stopped every day after school for treats from John’s bottomless bag of lollipops. He also read voraciously. The house was full of books.

In March, 1938, a collection of paintings O’Shea had created in the deserts of Arizona and New Mexico went on exhibit in Tucson. The local paper reported that a “visiting artist of note” who insisted on not being identified praised O’Shea “because of his enthusiastic virility, his feeling for color — everything seems so alive, spontaneous. His brush strokes are definite; nothing hesitates.”

Herbert Tschudy, curator at the Brooklyn Museum, was there, a member of the Eastern art establishment. His professional opinion:

O’Shea paints subjects that other artists never attempt. He paints giant cacti, and he does it amazingly well. Few artists can paint them at all without making them look like so many telegraph poles which form lines that will destroy any composition.

A bystander who overheard Tschudy’s comments argued that O’Shea sacrificed form for color. Tschudy replied:

I would not say that any of these paintings is without form, but rather that form is simplified. O’Shea is really one of our great artists today. I hope we can get this exhibit to Brooklyn.

In the flow of 30 years, critics repeatedly struck the note that O’Shea never suffered the self-conscious preoccupation with technique that flawed lesser talents. They all agreed that he knew and mastered technique; but mastered, it was as natural and subordinated as breathing.

John and Molly O’Shea had no children. When he died his Carmel house was filled with oil paintings and watercolors. His late wife’s sister was the inheritor, and the house and paintings eventually came to the sister’s two daughters, O’Shea’s nieces. One of them, Molly, named after her Aunt Molly, was married to my famous brother Morris Richard Jeppson.

Some paintings were distributed to family members, and many others were sold through Laky Galleries in Carmel. The decision was made to sell the impressive residue in block, and I was given the opportunity to find a buyer.

I researched and wrote an introductory biography and began working collectors and investors. But the paintings were in California, and I lived in the Washington, D.C. suburbs. From the many I worked, my best prospect was a Fellow in the American Institute of Architects and the architect for the Quality Inns chain of motels, a man I knew quite well and respected.

A consultant friend found another man who professed an interest in obtaining the collection as an investment. I made arrangements to meet him in Carmel, where Molly would show us the collection piece by piece. He came with his girlfriend. As Molly brought out the paintings, I photographed them. They covered all of the artist’s career.

We looked and took pictures of the art all morning, went as my brother’s guests to lunch overlooking the ocean at Pebble Beach, went back to the house for more pictures.

I later decided that Prospect Two was less interested in the art and more interested in having a getaway to a place where he and the girl would not be recognized.

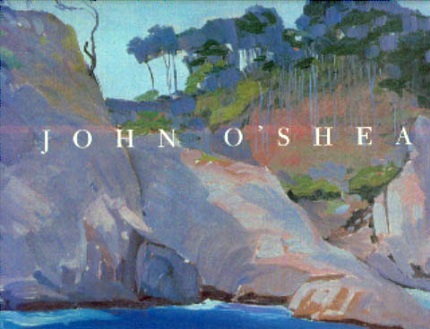

Dr. Walter A. Nelson-Rees and his partner James L. Coran of Oakland, California, were storied collectors of California art. I didn’t know them. They purchased the O’Shea collection from Molly. In 1985, they published a huge and authoritative book John O’Shea, 1876-1956, The Artist’s Life As I know It written by Nelson-Rees. The book catalogs all the O’Shea paintings they could discover. It lacks the portraits of famous people he is supposed to have painted.

Large in format (13.5 x 11.5") and illustrated throughout in color, it is a prodigious piece of scholarship. It is dedicated “To Molly Jeppson, whose memory of ‘Uncle John’ started the project.”

In 1989, with Coran the lead, they published an even bigger, much more expensive, limited printing If Pictures Could Talk, Stories about California Paintings in Our Collection. One painting per artist, O’Shea’s depicting was Fall Peak, a picture they did not know about when they published the O’Shea catalog. To my mind it was a nice picture but a far cry from the great O’Sheas they acquired from Molly.

In 1991, Conran and Nelson-Rees prepared to send the best of their great collection of California art on a museum tour. I assume it included the paintings from If Pictures Could Talk and many others. The collection was to be picked up by art transporters on Monday, October 20.

Late Sunday morning a small fire that had started Saturday in Berkeley suddenly became a raging conflagration driven by “Diablo Winds” of up to 65 miles per hour. Diablo means devil. Fed by the ubiquitous, non-native eucalyptus trees, which burn like tinder, the fire soon generated its own monstrous winds, the definition of a firestorm.

Inhabitants fled, with no time to save possessions. Ultimately the fire killed 25 people and injured 150 more. It destroyed 3,354 single-family homes and 437 apartments.

The entire Conran/Nelson-Rees art collection was destroyed — not only the art that was about to be picked up for museum tour but everything else they owned, including the one hundred or so O’Shea oil paintings and watercolors they purchased from Molly.

The fire also destroyed all their records and all the research they had done. The loss to art scholarship was terrible.

I have been researching and writing The Joy of Vision!, a book about California Impressionist William Henry Clapp. I knew that important Clapp paintings were in the Conran/Nelson-Rees collection and were part of the intended museum circulation.

In an exchange of emails, Conran (his partner was deceased) was able to name from memory several Clapp paintings that were lost. But our exchange was nearly 20 years after the fire, and he could not remember in any detail the hundreds of works of art that were destroyed, and there were no records he could turn to.

Despite the scattered references in the Conran book, my collection of slides is the only concise record of the oil paintings and watercolors that Molly sold to the distinguished California collectors.

The Diablo Wind did produce a Diablo Fire.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |