| Print | Back |  |

June 3, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art Repainting His Pastby Lawrence Jeppson |

Courts and collectors consider an artist to be the supreme expert in determining if a work of art attributed to him is real or fake.

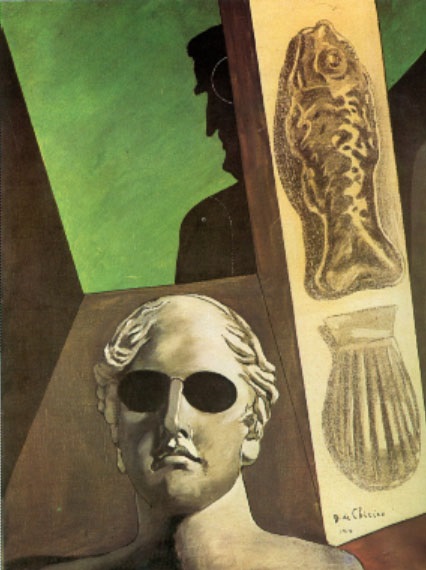

It doesn’t always work out that way. There are stunning exceptions, notably Italian Surrealist artist Giorgio DeChirico (1888-1978), who repeatedly upset this traditional apple cart.

If an artist is dead, the hierarchy of expertise passes on to the artist’s family and then to the artist’s principle dealer, if he/she had one. An artist’s wife, mistress, model, or children may have a usable understanding of the artist’s work — or they may be abysmally ignorant. Yet most courts would give these individuals the second-highest level of credence.

If the family is gone, or has been discredited, the next line of authority can become a minefield of dispute between dealers and experts. Opinions may be based upon issues such as provenance (where did the art come from?), esthetics (is that the way the artist painted?), or scientific examination (what do the white-coat lab analysts say?).

The German painter Max Liebermann (1847-1935) was once described to me as the artist who introduced Impressionism to Germany. He used inherited money to acquire and show a substantial collection of Impressionist paintings, but his own art was a far cry from his French contemporaries, and of all the countries whose artists were smitten with Impressionism, there was virtually no impact in Germany. In the huge and comprehensive book World Impressionism (Norma Broude Editor, New York, 1990) there is no chapter on German artists.

Liebermann, however, made a wry observation about this question of authenticity. “Critics are useful because they will tell the public our bad pictures are fakes.”

The Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) became so famous that his visage is seen on Switzerland’s 100-franc notes. Yet he was inept as a manager and careless as a record keeper. He lost track of what plaster models he had cast, allowing different bronze foundries to cast the same models. These in turn might become the gist for unauthorized copies and forgeries. On occasion Giacometti was unable to tell which bronzes were genuine and which were not, leaving the question of authenticity in limbo.

This dilemma passed on to the second level of authentication, his wife, who created the Giacometti foundation (the third level) in Paris in an effort to sort the good from the bad. The foundation’s task has not been made easier by Robert Dressen, a wealthy German-born failed painter turned art forger who now lives, untouchable, in Thailand. Dressen claims to be responsible for 1300 fake Giacometti castings.

DeChirico was born in Greece of Italian parents. His father, like Whistler’s father in Russia, was a builder of railroads. He died in 1905, and the next year the boy moved to Munich, Germany and entered the Academy of Fine Arts. In 1909, he moved to Italy, and the next year he painted the first of the metaphysical town-square paintings which would make him famous.

In the summer of 1911, he went to Paris to join his brother, who was on the jury for the coveted Salon d’Automne. With this connection, three of DeChirico’s paintings were accepted for the Salon. For a decade his brooding metaphysical paintings affected Paris. These were discovered by Surrealist painter, writer André Breton in the gallery of dealer Paul Guillaume, whom we met in my “Moments in Art” about Albert Barnes. Breton accepted DeChirico into the Pantheon of Surrealism.

But DeChirico became dissatisfied. He became infected with a compulsion to turn his art from the avante-garde to forgotten classicism. In the eyes of those whose views mattered, DeChirico’s art went downhill for the rest of his long life.

DeChirico’s response to this took a strange, conflicting duality. To get money, he would forge his own works, paint something in his old style, though he hated it, and then backdate it to make it seem from the period of his acclaim. Or, he would attack a genuine older painting, claiming he had never painted it, that it was a fake.

This caused consternation in the art market.

Maurice Grinspan was a successful Paris lawyer and a good friend. I was in Paris to testify before the examining magistrate in the Algur Meadows-Fernand Legros art forgery case I wrote about a few weeks ago. Maurice knew there was an important trial going on in one of the storied courtrooms that would interest me. He was so right.

DeChirico had denied the authenticity of an important metaphysical painting from his early period. His declaration destroyed the value of the painting. The owner filed a lawsuit to force the artist to admit that the painting was genuine. As defendant, DeChirico was in the courtroom as his alleged duplicity, assembled by the examining magistrate, was laid bare.

There was overwhelming evidence, and the plaintiff defeated DeChirico. The painting lost its tarnish and again became a genuine and accepted work from the artist’s best period.

| Copyright © 2025 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |