| Print | Back |  |

May 20, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art Fabulous Find, Fowl Intrigueby Lawrence Jeppson |

“To everyone is given a gift.” That’s Gospel. Different people have different gifts.

“Unforgettable” is a television series starring Poppy Montgomery as a homicide detective who remembers everything she has ever seen. In real life, actress Marilu Henner is one of the rare possessors of this ability. The phenomenon is so rare that “60 Minutes” could identify only a handful of people who possess this unforgetting gift.

I have written previously about my friend Nat Leeb (1910-1994), artist, collector, and connoisseur. He possessed a variant of that gift. Seemingly, he could remember every painting he had ever seen, live or in illustration.

This ability led to one of our more notable — or notorious — adventures, which took several years to play out.

Nat freely shared this gift. On one of our four trips visiting museums around the country we stopped in Raleigh to see the North Carolina Museum of Art. A spectacular new museum was nearly finished, and its architect took us through it room by room. The museum’s art was still in the old museum, and the director and assistants gave us a tour.

When Nat commented on several displayed pictures — some were more important than their attributions — the museum staff was so impressed that they took us into the vaults to see many of the pictures that were not on display. A secretary made copious notes of everything he said. When a painting perplexed him he said he would research it back in Paris so he could better answer their questions.

Three weeks ago I wrote about him in the context of the dealer who had sold fake paintings to Texas millionaire Algur Meadows. The Examining Magistrate (Juge d’Instruction) who examined me was so impressed by the previous testimony Nat provided that he asked for Nat’s advice on some art he owned. The Magistrate was another of many who sought the same counsel.

I met Nat through my good friend tapestry artist Mathieu Matégot. They lived on the same cul de sac in Paris. At the time I had begun organizing small commercial art galleries in many American cities and was looking for artists that I could show in collections that would circulate from city to city. Leeb (pronounced Leb) became one of my artists.

Shipments of art came from France, and from a headquarters in New Jersey we — Art Circuit Services — organized, framed, packed, and shipped the collections.

I was living in Bethesda, Maryland, and needed to drive thousands of miles around the country to launch my enterprise. I did not know Leeb very well, but I told him that if he and his wife, Paule, wanted to accompany me they were welcome as long as they paid for their own meals and motel rooms.

I met them on the New York docks. They brought with them their two-year-old daughter and a refugee Jewish governess whose father had once been financial advisor to deposed King Farouk of Egypt. The child and governess were taken to Bethesda to spend nearly two months with my wife and young children while the Leebs and I traveled.

I was a little nervous when I met the family in New York. I had offered to take them with me, but I didn’t really know if they had the means to pay for their meals and accommodations. To allay my unvoiced fears, the first thing Nat did while still on the dock was to reassure me of his wealth by showing photos of two magnificent Degas race track pastels he had just acquired.

(Before Nat left for home two months later he wandered through French and Company in New York, bought a misattributed painting, and sold it, properly identified, in Paris for more than enough profit to pay all the expenses of the trip.)

One of our stops was in Minneapolis, where I had arranged for Nat to have his first American showing.

Halfway through our circuit, Nat, Paule, and I stopped in the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, where there was an exhibition of American Trompe l’Oeil art featuring William Harnett, John Frederick Peto, and other like artists of the 19th Century. These forgotten artists had been rediscovered by Alfred Frankenstein, the art and music critic for the San Francisco Chronicle. Frankenstein’s recent book After the Hunt found and identified these artists whose still-life paintings are so realistic and deceiving that you want to pick up the objects depicted.

Skip ahead two years. The Leebs and I are making another museum pilgrimage, this time meeting with many museum directors. On that first trip we saw no Harnetts or Petos, except for that Santa Barbara museum. This time we found these artists well represented on museum walls, a direct result of Frankenstein’s book.

This set off Nat’s total art recall.

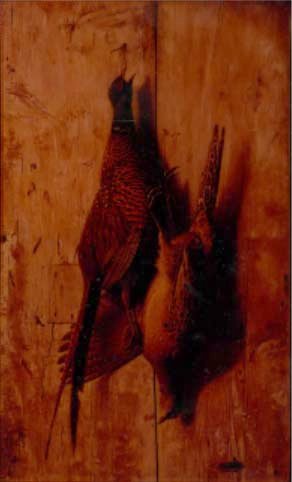

While Nat was living in Germany, well prior to World War II, he had painted some pictures to hang on the walls of a hunting lodge. Nat remembered a couple of paintings already at the lodge that were appropriate to the setting. One showed a pair of pheasants, one male, the other female, hanging on a weathered wood wall. The other painting depicted a rabbit hanging on a wood door that is even more weathered than the first picture. The game, wood, and hinges looked very real.

There were no identifying signatures. They are fabulous paintings, but who had painted them?

Nat returned to Europe and set off to find his former German patron. Despite the intervening years and the conflict that destroyed so much, Nat found him. The man was old and about to sell his hunting lodge. Nat bought the paintings.

Nat took them to conservators at the Doerner Institute, Munich, whose task is to provide scientific preservation of the Bavarian State Painting Collections. Technicians discovered that the paintings had been relined. That is, a second canvas had been glued to the back of the aging original for strength. Removing this relining revealed the paintings’ authorship. Both were boldly signed and dated on the back by Harnett!

Signatures can be forged. The paintings would have to be authenticated by the one expert in the world who could not be challenged: Alfred Frankenstein.

Frankenstein came to Paris to see the paintings at the precise time I was there with my daughter Caroline. We met him when he carefully inspected Nat’s paintings. He was not ready to give Nat his opinion.

Frankenstein played the clarinet in the Chicago Symphony before moving to California, where he became the art and music critic for the San Francisco Chronicle. Each Sunday edition of the paper included a tabloid section summarizing the national, state, and local news of the week and carrying the stage, music, art, and movie reviews. In Carson City, Nevada, this Sunday edition became a part of our family reading, and growing up I read Frankenstein’s reviews every week.

I was thrilled to meet him. I was even more thrilled when he said that he used my book The Fabulous Frauds as source for some of his lectures.

Later that day Frankenstein called me at my hotel. He wanted to know how long I had known Nat, and he wanted me to tell him the story of how Nat had obtained the paintings.

At the end of our conversation — before we all went out together for dinner — he said to me, “These are the most important Harnett paintings to be found in years.”

That declaration does not end the saga of these paintings.

Harnett had studied art in Germany, and Nat sent the paintings to the Cincinnati Art Museum to be part of a show of 19th Century American painters who had done the same. Frances and I drove to Ohio for the opening of the exhibition.

Nat then either consigned or sold the paintings to Steven Straw’s gallery in Newburyport, MA. (Nat and I had some previous experience with Straw, but that’s a different story.)

Straw was a crook.

Among other frauds, he would sell half interest in a painting (which he might not even own) to more than two different people. He was found out, charged, thrown into involuntary bankruptcy and sent to prison. The gallery’s inventory, including the two Harnetts, was put up for auction.

From at least two different sources I was informed that there was a conspiracy among a number of dealers to discredit the paintings, to allege they were fakes, and to poison their auction appearance so they could be purchased for almost nothing. After which they would suddenly be declared genuine.

I received a call from the Maine Antiques Digest, an important trade publication, to which I gave a detailed recital of the history of the paintings, which it published.

My next call was from Alfred Frankenstein in San Francisco. The allegations had come back to him, and he was irate, to put it mildly — that his authority should be challenged! He reaffirmed his authentication.

The auctioneers could see what was happening. They heard what I heard. They withdrew the paintings.

Later they negotiated their private sale — as genuine Harnetts.

Auction houses do not identify purchasers. I have no idea where these two beautiful paintings went, but some institution, investor, or collector possesses two of the best fool-the-eye paintings Harnett ever created.

| Copyright © 2025 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |