| Print | Back |  |

May 6, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art When Hollywood Called Fribergby Lawrence Jeppson |

An infantryman during World War II, after demobilization Arnold Friberg set up his studio in San Francisco. In 1947, he was asked to join the faculty of the new School of Fine Arts being set up by Dean Avard Fairbanks, who was hired away from the University of Michigan and who wanted a name artist to teach painting and inject a new discipline into the commercial art courses.

In 1950 Friberg was commissioned to do a painting commemorating the centennial of the first Mormon Sunday School, which had been established in a log cabin by a Scottish convert. I believe this was first published in The Instructor magazine. This was the first Friberg art I can recall seeing.

It was seen by Adele Cannon Howells, the head of the Primary Association. She wanted Arnold to make a series of 12 paintings illustrating scenes from the Book of Mormon that could be used to teach children.

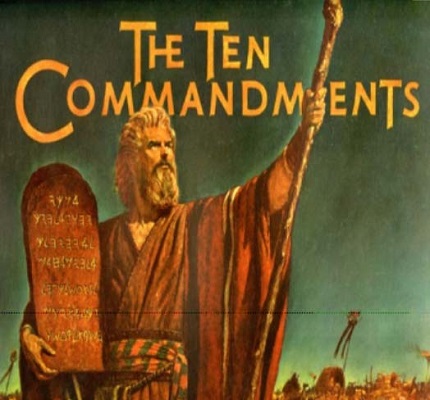

At this time, Cecil B DeMille was engaged in a frustrating worldwide search for an artist who could design costumes for the epic motion picture he was about to remake. He had not found any artist whose work he liked. A Swedish publisher had seen reproductions of the first Book of Mormon paintings and suggested that DeMille check out the artist.

DeMille asked Arnold if he would come to Hollywood for a month as a consultant. After the month, Arnold went home. But DeMille sent Friberg a request that he put his other obligations on hold and join his production company until the movie was finished.

Perhaps as a manifestation of his Scandinavian character, Arnold did not want to go. He had the Book of Mormon paintings to finish. Adele Cannon had raised her own money to pay for the commission, and the night before she died she had made Arnold promise he would finish them.

Looking for an excuse not to go back to Hollywood, Arnold sought out President David O. McKay, certain that President McKay would hold him to his commitment.

President McKay said to Arnold, in effect, the chance to work on this movie with DeMille was a chance of a lifetime. He should take it. The Book of Mormon illustrations can wait until the movie is finished, he said.

So Arnold returned to Hollywood — and stayed four years.

Duties that began as costume design expanded. As the two men worked together their relationship grew. DeMille would ask Friberg how he visualized a scene, and Arnold would paint it, and the painting would become the visual template for that part of the movie.

When the motion picture was finished DeMille produced a souvenir book that said:

The magnificent series of Arnold Friberg paintings in this book indicates why he has achieved fame as one of the greatest living interpreters of Biblical subjects. Combining rare artistic skill with a profound respect for the most minute historical details, he has imbued his paintings with dynamic realism unsurpassed by any contemporary religious artists. Cecil B. DeMille knew the thundering drama in Exodus and Deuteronomy demanded such an artist.

During preparations for shooting The Ten Commandments, Mr. DeMille lined the walls of his office with Friberg’s paintings. Friberg also designed the costumes for the principal men ...

Demille added his personal testimony: Among living artists who have dedicated themselves … to religious art, one stands out for his virility and warmth, dramatic understanding and truth. That man is Arnold Friberg. His fine paintings were a tremendous help to our art directors, cameramen, costume designers, screenwriters, and actors. Arnold Friberg’s work has been an inspiration to all of us from his profound reverence and knowledge, as well as his superb artistry.

Friberg’s paintings were exhibited all over the world, and more than a million copies of the book were printed and sold. It is unlikely any other living artist ever had that kind of public exposure.

He was nominated for an academy award in costume design.

In the vibrant, variegated world of art, there are powerful academics, critics, artists, and bystanders who believe that narrative art and illustrative art is not good art and, even if it were good, cannot be great.

At a time when American Pop Art was coming on strong, there was another movement centered in Paris called Op Art (Op for Optical). This art was based upon geometrical manipulation and was sometimes described as hard-edged. The gifted international high priest for this expression was Hungarian-born Victor Vasarely.

The high priestess was Denise René, who ruled the Op Art world from her Right Bank Paris gallery. One afternoon Denise scolded me without reservation. “All other art is decadent!” She meant every non-Op expression from any period, not just hers.

It is perfectly all right for any gallery to decide to specialize. Sometimes that is the key to survival, if not prosperity. But to put on blinders and see no good in any other expression is unbelievably narrow. The sad thing is that people who put on blinders miss a lot of rich visual experience. (This is true as well for individuals who cannot abide anything that is not easily recognizable.)

Friberg came in a long line of narrative or illustrating artists that goes back for centuries. On the American side there has been a passel of illustrators, good artists who are loved and esteemed. They bridge several generations, from Thomas Cole, who painted four paintings on the Voyage of Life in 1842 and which have their own elegant room in the National Gallery at Washington, to Norman Rockwell, who has his own museum in Stockbridge, MA.

In between them you have Frederick Remington , Charles Russell , and a host of other well-known Western illustrators.

When I think about Friberg, I like to quote a statement by Dr. Jonathan Fairbanks, distinguished curator emeritus, the Museum of Fine Art in Boston, a good landscape painter in his own right, and a friend of Arnold’s for more than half a century, and through whom I met Arnold:

In an era that seems dedicated to celebrating mediocrity — when the lowest common denominator governs much of our marketplace — it is refreshing to know an artist who is able and willing to swim successfully against currents of fashion and eloquently affirm his faith in mankind. His works show a reverence for nature in all its remarkable manifestations... The glory of the western American landscape, the magnificent of the horse, and the nobility of human endeavor are just a few of the many themes in Friberg’s art — an art that makes history seem to live.

These were the qualities that Cecil B. DeMille found in Arnold Friberg — not only in his art but in his soul — that bound the two men, working together, like father and son.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |