| Print | Back |  |

February 13, 2013 |

|

Rambling Thoughts on Church History The American Presidency and the Mormons Part II: Since 1900by James B. Allen |

In our last column we dealt with the tense and sometimes tortuous relationship between the Mormons and the Presidents of the United States in the nineteenth century. With the coming of statehood for Utah in 1896, that relationship changed. No longer did the President and his party feel a need to prosecute the Church or its members, and gradually the national image of the Mormons changed from negative to positive. It seems, in fact, that the views of the various presidents were more positive throughout the century than those of the American people in general, possibly because they knew more about them. Most presidents were highly amicable with Church leaders and in some cases they became close friends. In addition, Mormons were often appointed to important federal positions, sometimes at the cabinet level. This was not because they were Mormons but simply because they were highly capable in their respective professions, but the fact that they were appointed demonstrated that, at least at the presidential level, American anti-Mormon bias disappeared. From the beginning of the twentieth century, Mormons played increasingly prominent roles in American business, political life, governmental activity, education, the arts, and all other aspects of American life.

During the nineteenth century Church leaders sometimes took a stand with regard to presidential candidates, but when they did so that stand reflected what seemed to be in the best current interest of the Church. As the twentieth century began the situation was different. No longer did either major party seem to threaten the existence of the Church, and no longer did it seem, as it had to Joseph Smith, that Church members could not be comfortable supporting any of the major candidates. This is not to imply that Church leaders ignored political activity. Quite to the contrary, many participated actively in national politics, and in both major parties. At times some Church leaders even publicly supported certain presidential candidates, but in each case the support was on the basis of personal political preference rather than for any apparent religious or doctrinal reason.

Historian D. Michael Quinn once described the twentieth century metamorphosis this way: “By 1890 Congress and the Supreme Court were prepared to deny civil rights to all members of the LDS church. In a stunning turnabout, a century later the LDS church had become the darling of the Republican White House.”2 At no time was this more clear than during the Reagan administration, though every President after 1900 had a positive relationship with the Church and its leaders.

By 1900 the personal preference of many Church leaders had gravitated toward the Republican Party. For one thing, this party seemed to better represent the interests of American business and industry, with which many leading Mormons were becoming closely identified. At the same time other leaders, such as Heber J. Grant and B. H. Roberts, were prominently identified with the Democrats.

In the election of 1896 Republican William McKinley faced Democrat William Jennings Bryan, and the major issue was ratification of the administration’s expansionist activities. McKinley won handily. During the campaign in Utah, charges were made that the Church was exercising its influence to sway the election, which the Church-owned Deseret News vigorously denied on November 5, the day before the election:

The Deseret News is authorized to state most emphatically that the Church is not engaged in politics. That no such instructions as those referred to have been sent forth from the First Presidency. That no one, however high in ecclesiastical position, is empowered to use Church influence in political affairs. That every member of the Church is absolutely free to vote according to his or her personal convictions or party fealty. That it is not right to exercise ecclesiastical authority to promote partisan purposes. … And that it is contrary to that personal freedom that the Church maintains, to sway voters by dictation, or suggestion, or open or covert means as coming from the “brethren,” signifying the leaders of the Church.

The editorial recognized that prominent Church officials had been active in both parties during the campaign but rightly pointed out that as citizens they had “as much right to work for the prevalence of their convictions as other citizens, but no more.” Elder Heber J. Grant of the Quorum of the Twelve was impressed with Bryan, whose views, he thought, were very much in harmony with those of the Church. Elder John Henry Smith, on the other hand, did much to establish the Republican Party in Utah and even campaigned for McKinley in various western states.

That year 83 percent of the people of Utah voted for Bryan, clearly reflecting the long-standing LDS dismay with the Republican Party because of its efforts to destroy plural marriage, which amounted in the eyes of many Mormons to an effort to destroy the Church. Nevertheless, early in McKinley’s administration the President was visited by George Q. Cannon, First Counselor in the First Presidency of the Church, who asked him not to exclude Mormons from various federal appointments. He responded by appointing George Albert Smith (a future President of the Church) as receiver of public moneys and disbursing agent in the U.S. Land Office in Utah.

In 1900 McKinley again defeated Brian for the Presidency, but this time he had the support of 51 percent of Utah’s voters. Mormon attitudes toward the President had gone through a major change, partly because it appeared that he was trying to treat them fairly. Tragically, less than a year into his second term, McKinley was assassinated.

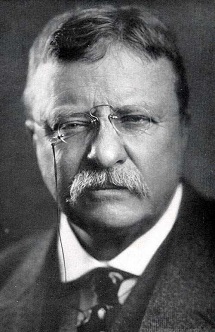

McKinley was succeeded by Theodore Roosevelt. In a sense, his presidency completed what was begun under McKinley: a new era of mutual respect and warm relations between the American President and the Latter-day Saints. Roosevelt already knew and respected several Church leaders and, right from the beginning, it was clear that he was a friend of the Mormons. Reed Smoot, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, was elected to the United States Senate in 1902. President Roosevelt did what he could to help Elder Smoot secure his seat in the face of bitter anti-Mormon opposition in the Senate to his confirmation.3 Roosevelt also visited Utah in 1903 and became the first President to speak in the Salt Lake Tabernacle. He continued to show his friendship for the Mormons in various ways.

Roosevelt easily won reelection in 1904, largely because he had the support of both the eastern industrialists and progressive politicians. In Utah that year, the Democratic Party was hurt when it placed in its national platform a plank calling for the extermination of polygamy and the complete separation of church and state. This implied an endorsement of anti-Mormon groups who accused the Church of continuing to practice plural marriage, and resulted in many Latter-day Saint Democrats moving into the Republican camp. The Church continued to disavow any intent to tell its members how to vote, and in an election-eve editorial emphatically told them to “vote as they please.” Nevertheless, some Church leaders made clear their support for Roosevelt. Elder George Albert Smith of the Quorum of the Twelve even campaigned openly for him. Roosevelt garnered 61 percent of the vote in Utah.

Despite its continuing nonpartisan stance, the Church did take a position on a few issues in that era that leaders considered to have important religious overtones. These included prohibition and Sunday closing laws. Even on these issues, however, members who voted differently were not considered disloyal. On other matters, including presidential elections, the Church continued to maintain official neutrality. In an official address to the world in 1907 the Church declared itself in favor of the “absolute freedom of the individual from the domination of ecclesiastical authority in political affairs.”4 Such disclaimers had to be repeated many times in the coming century.

In 1908 William Jennings Bryan made his third bid for the presidency. The Deseret News was friendly to him, but on June 19 it suggested that William Howard Taft, the Republican candidate who had been hand-picked by Theodore Roosevelt, might be the best man. This was followed inevitably by disapproving cries of undue mixing of church and state, and on June 23 the Deseret News again emphatically denied Church partisanship, even though it had said “a good word for a man who a great portion of this nation honor.”

In a way the whole 1908 campaign illustrates how difficult it is for Church leaders with strong political opinions of their own to promote those opinions without criticism. It appears that most of them, including President Joseph F. Smith, favored Taft, but even though they tried to separate their politics from their religion, their political opponents continued to make charges of unrighteous Church influence. In the end, 56 percent of Utah’s voters cast their ballots for Taft, who won the election.

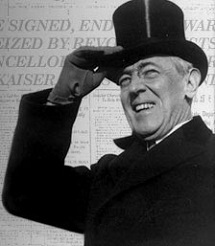

The issue of Church interference in politics became even more intense in 1912, when Taft was running for reelection against Woodrow Wilson. Wilson won the election largely because Theodore Roosevelt, dissatisfied with Taft’s lack of progressivism, split the Republican Party by forming his own “Bull Moose” party. In Utah, President Joseph F. Smith personally endorsed Taft in the pages of the Improvement Era,5 largely on the basis of Taft’s having avoided war with Mexico by not intervening in behalf of certain American interests there.

President Smith’s endorsement was immediately interpreted as an appeal to Church members to vote for Taft, although in a subsequent statement he insisted that it was merely a statement of personal preference, and the Deseret News again urged its readers to vote their personal convictions. In the end, only 37.5 percent of Utah voters cast their ballots for Taft and the combined vote for Wilson and Roosevelt exceeded that for him. Clearly, most Utah Saints were convinced that President Smith was sincere in implying that his endorsement of Taft did not limit their choices. However, because he had a slight plurality, Utah’s four electoral votes went for Taft. The only other state to cast its electoral votes for him that year was Vermont.

In 1916 President Woodrow Wilson ran for reelection and was opposed by Republican Charles Evans Hughes. With war raging in Europe, Wilson won largely on his record of having kept America out of the conflict. Utah also voted for Wilson with nearly a 58 percent majority and no apparent preference stressed by the Deseret News or by Church leaders.

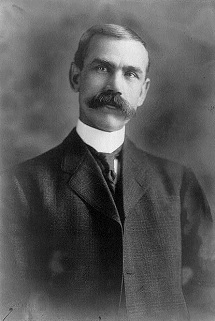

Wilson was the first president to appoint a member of the Church to a major position in his administration. This was James Henry Moyle, Jr., founder of the Utah Democratic Party. (Moyle once said of himself that he had two religions: Mormonism and the Democratic Party.) He served as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury from 1917 to 1921.

Despite his best efforts, Wilson was unable to keep America out of the war during his next term. As the war ended in 1919, Wilson went to Europe and inaugurated a great debate that not only divided the nation but also divided Church members at all levels. He proposed the creation of a League of Nations that, hopefully, would prevent future wars. Church leaders were openly divided on the issue. Elder Reed Smoot, still a United States Senator, vehemently opposed the League, arguing that it would undermine American sovereignty. J. Reuben Clark, Jr., then a solicitor in the State Department, was, in effect, representing Elder Smoot when he gave an address in the Salt Lake Tabernacle opposing the League and even using the Book of Mormon in support of his position. B. H. Roberts, a member of the First Council of the Seventy, followed the next week with an address supporting the League and also using the Book of Mormon to support his position. Three members of the Quorum of the Twelve, George F. Richards, David O. McKay, and Joseph Fielding Smith, also supported the League, with Elder Richards even declaring in a stake conference his belief that President Wilson had been raised up by the Lord and that the League was inspired by God. In September President Heber J. Grant announced in another stake conference that he supported the League, but he also made it clear that this was his own feeling, not an official Church position, and that the LDS Scriptures could not be used on either side of this debate. In the end, the League of Nations was formed but the Senate refused to ratify the treaty that would have made the United States a member. Senator Smoot was one of the Senate’s “irreconcilables” who prevented ratification.6

A major political issue on which Church leaders took a united stand in this era was prohibition, for which a third national party was formed and which led to the Eighteenth Amendment in 1920. The First Presidency donated $1,000 to the prohibition cause, and Elder Heber J. Grant of the Council of the Twelve was president of Utah’s prohibition league. However, there was no endorsement of the Prohibition Party candidate by Church leaders.

The Church continued its nonpartisan stance on other issues and in the next several elections the charge that church and state were too closely intertwined all but disappeared. As most Americans, the Latter-day Saints seemed satisfied with the apparent prosperity and good times of the 1920s. They joined with the rest of the nation in generally casting their votes for the Republican candidates, who seemed to represent the economic interests presumably responsible for the good times.

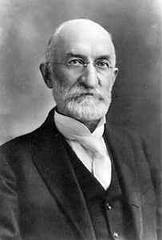

Warren G. Harding, a Republican, was elected in 1920 by a huge popular as well as electoral vote, including the votes of Utah. His nomination was secured partly because of Senator Reed Smoot’s behind-the-scenes political maneuvering and afterwards he offered Senator Smoot the position of Secretary of State if he were elected. The apostle declined, saying he would rather stay in the Senate. The friendship continued, however, and Senator Smoot not only gave the President a Book of Mormon but also at times shared his gospel beliefs. On one occasion the President’s wife became seriously ill. He telephoned the senator late at night, asking him to come to the White House and give his wife a blessing. The senator, of course, took with him a bottle of consecrated oil and administered to Mrs. Harding. After Harding’s death Senator Smoot was baptized for him and President Heber J. Grant was the proxy for his temple endowment.

Harding died of a heart attack in 1923. He was succeeded by Calvin Coolidge, who was then elected in his own right in 1924. His popular vote in Utah was 49 percent, with the rest of the votes divided between Democrat John Davis and Progressive candidate Robert LaFollette.

In general the Latter-day Saints had a warm and friendly relationship with President Coolidge. He met and traveled with Reed Smoot frequently and he appointed J. Reuben Clark as undersecretary of state.

It seemed only natural that Church leaders should have the same warm relationship with Herbert Hoover, the Republican who was elected in 1928 to succeed Coolidge. His popular vote in Utah was 54 percent. Hoover, too, developed a close friendship with Reed Smoot. The senator, who even went fishing with him, was one of his close advisors. In 1930 the senator married his second wife, Alice Taylor Sheets, and planned a honeymoon in Hawaii. In the Senate, however, there was a crucial debate and vote on the London Naval Treaty and the President was anxious for Senator Smoot to be there. He therefore asked the senator to return to Washington from Salt Lake City and invited him to spend his honeymoon in the White House. Another indication of the affection Church leaders and President Hoover had for each other came when President Heber J. Grant wanted J. Reuben Clark to become a counselor in the First Presidency. However, Clark was then U.S. Ambassador to Mexico and he was concerned that the President would think of him as a deserter in a crucial time. Out of respect for Hoover, therefore, the President of the Church functioned with only one counselor until President Hoover was out of office, over a year later.

Despite the fondness Church leaders felt for President Hoover, in 1932 disillusioned Mormon voters in Utah, along with the majority of the American people, changed their minds about the Republican Party. After three years of the Great Depression, Americans voted into office Franklin D. Roosevelt, who seemed to promise the kind of imaginative leadership in the midst of serious economic crisis that the Republicans had failed to produce. Utah voters supported Roosevelt by 56.5 percent, as opposed to 41 percent for Hoover.

Although President Heber J. Grant announced his own support for the reelection of Herbert Hoover and of Senator Reed Smoot, who had been a leading Republican senator for nearly thirty years, he did not intend to commit the Church to such a vote. On October 31, Elder James E. Talmage of the Council of the Twelve made it abundantly clear, in an article in the Deseret News, that the Church had no candidate. In the end Utah not only gave its electoral votes to Roosevelt, but also turned Reed Smoot out of office in favor of his Democratic opponent, Elbert D. Thomas, who received 56.7 percent of the popular vote.

In his effort to pull America out of the Great Depression, Roosevelt pushed through Congress a series of actions known as the New Deal. His programs took the federal government into areas where it had never yet tread, and permanently increased its role in the American economy. Though a long-time Democrat, President Heber J. Grant was also a long-time businessman and he immediately took a dislike to the New Deal, considering it a dangerous step toward socialism. He was joined in his criticism by his counselors, J. Reuben Clark and David O. McKay. Other General Authorities, however, including Presiding Bishop Sylvester Q. Cannon, publically applauded Roosevelt’s actions.

During the 1932 campaign, the Democratic platform included repeal of the prohibition amendment. This, of course, was strongly opposed by the First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve. But prohibition was repealed in 1933 with the ratification of the Twenty-First Amendment. It took thirty-six states to ratify it and, despite President Grant’s best efforts to stop it, and finally to his chagrin, Utah became the thirty-sixth state. However, this at last demonstrated that the Church did not control politics in Utah.

In the next two elections the position of the Church seemed a bit ambiguous. In 1936 Roosevelt ran for reelection against Republican Governor Alfred M. Landon of Kansas and won a resounding victory, both in Utah and in the nation. Opponents of Roosevelt were fearful for human liberty under what appeared to be a revolutionary increase in the power and activity of the federal government under the so-called New Deal. Nevertheless, 69.3 percent of Utah voters favored him.

The Deseret News severely criticized President Roosevelt for characterizing the Constitution as having come from “horse and buggy” days. Actually, Roosevelt had only angrily accused the Supreme Court of using an outdated interpretation of the interstate commerce clause when it overthrew on constitutional grounds certain legislation that he considered keystones of his economic program. But the News made an impassioned plea for support of the Constitution and endorsed Landon, who had declared that he would keep it inviolate. When the inevitable outcry came, President Heber J. Grant took full credit for the statement in the News. Church members in Utah again considered President Grant’s statement as a personal declaration and not binding in terms of faith. Roosevelt enjoyed a 69.3 percent majority in the state.

The Church-owned newspaper again opposed Roosevelt in 1940, using arguments against the propriety of a third term as its emphasis, but 62.3 percent of the voters of Utah joined with the nation in giving him an overwhelming victory over Republican businessman Wendell Wilkie. In 1944, the News took no position as Roosevelt ran for a fourth term and was elected, this time with nearly 61 percent of Utah’s voters supporting him over Republican Governor Thomas F. Dewey of New York.

Meanwhile, despite the opposition of Mormon leaders to the New Deal, President Roosevelt had friends among the Latter-day Saints and was cordial toward the Church. He appointed Franklin D. Richards, who later became an LDS General Authority, as head of the Federal Housing Administration in Utah. James Henry Moyle, Jr., (who had been a mission president since serving in the Wilson administration), became Commissioner of Customs and then, in 1934, assistant to Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau. Marriner S. Eccles was appointed to the Treasury Department and then made chair of the Federal Reserve. Presiding Bishop Sylvester Q. Cannon became an advisor to the New Deal’s Public Works Administration. J. Reuben Clark, Jr., by then a member of the First Presidency, was asked in 1933 to serve as a delegate to the Pan-American Conference in Uruguay. President Clark, with President Grant’s permission, agreed, even though it meant taking four months off from his Church duties. Later President Roosevelt asked President Clark to serve his administration as president of the Foreign Bondholder’s Protective Council.

One of the great compliments President Roosevelt paid the Church appeared in a letter to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his wife, Clementine, on January 4, 1944. As quoted in Michel K. Winder’s delightful book Presidents and Prophets, Roosevelt wrote:

I find the enclosed clipping on my return home. Evidently, from one of the paragraphs, the Dessert News [sic] of Salt Lake city claims there is a direct link between Clemmie and the Mormons. And the last sentence shows that, Winston is a sixth cousin, twice removed. All of this presents to me a most interesting study in heredity.

Hitherto I had not observed any outstanding Mormon characteristics in either of you—but I shall be looking for them from no[w on].

I have a very high opinion of the Mormons—for they are excellent citizens.7

In subsequent presidential elections Church leaders, as individuals, obviously favored certain candidates, but there was no effort to promote political uniformity in the Church. However, some people continued to attempt to convey the impression that there was a Church position. Such efforts came from at least two sources: (1) critics of the Church who habitually delighted in finding something with which to discredit it, and (2) certain politically-minded Saints who sought to equate their own political beliefs with the doctrines of the Church in order to obtain greater support from Church members.

Church leaders were critical of both, and in several official as well as unofficial statements continued to decry any attempt to equate the Church with any party or candidate.

Franklin D. Roosevelt died suddenly in April 1945 and was succeeded by Harry S. Truman. Church President Heber J. Grant died a month later and was succeeded by George Albert Smith. These two new presidents developed a warm and earnest friendship, often sharing political and religious ideas through the mail.

World War II ended with the surrender of Japan in August 1945. In November President Truman was delighted when President Smith told him of the Church’s desire to ship goods to the suffering Saints in Europe. When he asked how long it would take to get them ready, he was taken by surprise when President Smith replied that the supplies were already waiting to be shipped. All the Church needed was government cooperation to arrange transportation, which Truman readily gave. In later years, until President Smith’s death in 1951, there was a continuing warm and friendly relationship between the two.

In 1948 Truman ran for and won the American presidency in his own right, against Republican Governor Thomas E. Dewey of New York. In Utah, he received 54 percent of the popular vote, suggesting that for the most part the Latter-day Saints not only still felt good about him but also generally accepted the programs of the Democrats.

President George Albert Smith’s successor, David O. McKay, was also highly respected by Truman, though the relationship was never quite as warm as it was with President Smith. Nevertheless, when he visited Utah in 1952, campaigning for Democratic presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson, Truman and President McKay got along very amicably, partly, I assume, because of President McKay’s strong statement of neutrality in General Conference on October 6:

… Twice, during the conference, reference has been made to the fact that we are approaching a general election, in which tension becomes high; sometimes feelings are engendered; often false reports are made; and innocent people are misjudged.

Recently we heard that in one meeting, for example, it was stated authoritatively by somebody that two members of the General Authorities had said that the General Authorities of the Church had held a meeting and had decided to favor one of the leading political parties over the other, here in this state, particularly. …

This report is not true, and I take this opportunity here, publicly, to denounce such a report as without foundation in fact.

In the Church, there are members who favor the Democratic Party. There are other members who sincerely believe and advocate the principles and ideals of the Republican Party. The First Presidency, the Council of the Twelve, and other officers who constitute the General Authorities of the Church, preside over members of both political parties.

… The welfare of all members of the Church is equally considered by the President, his Counselors, and the General Authorities. Both political parties will be treated impartially.8

Truman arrived in town the next day. President McKay met him at the railroad station, had breakfast with him, and went to Provo with him, where he gave a strong political campaign speech in the BYU stadium. After it was all over President McKay recorded in his diary that, because of their association that day, he had a higher opinion of President Truman.9

However, despite Truman’s best efforts, Utah followed the nation in 1952 and helped elect Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower. He won nearly 59 percent of the popular vote in Utah. The new president promptly selected Ezra Taft Benson, a member of the Council of the Twelve, as his Secretary of Agriculture. By 1956 the fact that Elder Benson was in the cabinet, together with the well-publicized spirituality of Eisenhower, seemingly convinced some Latter-day Saints that the Republican Party was the Church party, which, of course, the Deseret News emphatically denied. Nevertheless, with Elder Benson traveling the country campaigning for the President’s reelection, every county in Utah favored Eisenhower as he garnered 65 percent of the state’s popular vote.

In 1960 President David O. McKay, known to be a Republican, personally endorsed Vice President Richard M. Nixon, who was running against Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, but when the national press picked it up as a Church endorsement he quickly made it clear that he had been misunderstood. He declared that his endorsement was of a personal nature for the nominee of his party, that he did not intend for it to influence the state, and that “every member of the Church is free to make his own choice, to vote for anyone he sees fit.”10 Utah voted for Nixon by 54.8 percent but Kennedy narrowly won the national election.

In the meantime, Church members and leaders continued to be active in both political parties. Most prominent among them were Elder Ezra Taft Benson, a Republican, and Elder Hugh B. Brown, a Democrat, who in 1958 (the year he became a member of the Quorum of the Twelve) gave the keynote address in the state Democratic convention. Elder Brown appeared at the convention only after Elder Benson had stumped the country giving 123 speeches for Republican congressional candidates which, the Democrats believed, gave their nominees for the House of Representatives an unfair advantage in Utah. In an effort to balance the situation, the Democratic state chairman and others visited President McKay and asked him to permit Elder Brown to make public his association with the party. The Church president agreed, after which Elder Brown not only appeared at the convention but also appeared publicly several times to endorse Democratic candidates. Among others, he personally endorsed David S. King, the candidate from the second congressional district. This helped him cinch the election with a narrow margin of 51 percent of the votes. The Republican candidate in the first district, incumbent Henry Aldous Dixon, won by a slightly larger majority.

After his election President Kennedy had the respect of LDS Church leaders. At least one of them, Elder Hugh B. Brown, also clearly supported him politically. In addition, Kennedy had several Church members serving in various capacities in his administration. After he was assassinated on September 26, 1963, Church leaders genuinely mourned the loss and Hugh B. Brown, then first counselor to President McKay, represented the Church at his funeral. Memorial services were also held that day at the Church’s Chevy Chase chapel in Maryland, at the Tabernacle in Salt Lake City, and at Brigham Young University.

Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination in 1960, succeeded Kennedy. In 1964, opposed by Republican Barry Goldwater, he won the election handily, with all but six states giving him their electoral votes. In Utah he garnered 54.7 percent of the vote.

Johnson showed his high respect for the Latter-day Saints in various ways. In 1965 he became the first U.S. President to invite the Tabernacle Choir to sing at his inauguration. Later that year, at the request of President McKay, he forcefully intervened in the Defense Department in order to stop the apparent six-year-long discrimination against appointing LDS chaplains.

Even though President McKay was a Republican, he and President Johnson enjoyed one of strongest, most friendly relationships ever between a Church president and an American president. Early in his administration Johnson invited President McKay to the White House and sought his spiritual advice. They also met on other occasions and greeted each other regularly by telephone and telegraph on their birthdays.

In 1968 it appeared that, for the first time since Joseph Smith, the Saints might have their own presidential candidate. George Romney, governor of Michigan and former president of the Detroit Stake, made a serious bid for the Republican nomination. However, Richard Nixon again became the nominee and, by a narrow margin, defeated his Democratic rival, Hubert H. Humphrey. Nixon picked up 56.5 percent of Utah’s votes, a larger percent than in all but two other states. Four years later Nixon was reelected, this time with 68 percent of Utah’s vote.

After that it was almost a foregone conclusion that Utah would always vote for Republicans, at least at the Presidential level. Before 1968 Utah voters went for the Democratic candidate eight times and for the Republican ten times. In 1968 and every Presidential election since then, Utah has voted Republican. In addition, a 1988 study showed that 46 percent of the Mormons throughout the country were Republicans, 26 percent were Democrats, the same number were independent, and 1 percent was listed as “other.”11

However, during the 1968 campaign the Deseret News again emphasized its impartiality, and again Church leaders emphasized the Church’s political neutrality and the fact that good Church members could be comfortable in either party. Early that year President Hugh B. Brown gave a commencement address at Brigham Young University in which he beautifully portrayed the true spirit of political debate, cautioning the young voters not to engage in defaming personalities:

You young people are leaving your university at the time in which our nation is engaged in an abrasive and increasingly strident process of electing a president. I wonder if you would permit me, one who has managed to survive a number of these events, to pass on to you a few words of counsel.

First I would like you to be reassured that the leaders of both major political parties in this land are men of integrity and unquestioned patriotism. Beware of those who feel obliged to prove their own patriotism by calling into question the loyalty of others. Be skeptical of those who attempt to demonstrate their love of country by demeaning its institutions. Know that men of both major political parties who bear the nation’s executive, legislative, and judicial branches are men of unquestioned loyalty and we should stand by and support them, and this refers not only to one party but to all. Strive to develop a maturity of mind and emotion and a depth of spirit which enables you to differ with others on matters of politics without calling into question the integrity of those with whom you differ. Allow within the bounds of your definition of religious orthodoxy variation of political belief. Do not have the temerity to dogmatize on issues where the Lord has seen fit to be silent.12

Nixon got along well with the Latter-day Saints, even asking one of them, J. Willard Marriot, to chair his inaugural committee. In addition, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir sang at that event, as well as at his second inaugural. Nixon also appointed two active Church members to his cabinet: David M. Kennedy as Secretary of the Treasury and George Romney as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. In 1970 he visited Utah on Pioneer Day, July 24, and made some very complimentary remarks about the Mormons. Later that year he returned to Utah and gave an address in the Tabernacle on Temple Square. Unfortunately for his reputation, however, he was forced to resign from office in August 1974 because of his role in the infamous Watergate scandal.

Vice President Gerald R. Ford succeeded Nixon. He had a number of prominent Latter-day Saints among his circle of friends, and he was complimentary to the Church in 1975 for its role in assisting and placing Vietnamese refugees. He also appointed a few Mormons to various positions in his administration. However, Ford lost the election of 1976 to former Governor Jimmy Carter of Florida, though he got 62.4 percent of Utah’s popular vote.

President Carter met President Spencer W. Kimball on a few interesting occasions. The first was in 1976, while Carter was running for President. By that time it was practically pro-forma for presidential candidates to meet with the First Presidency of the Church—not that they were seeking advice, but because it was good public relations and would have been deemed an insult if they had passed through Utah without calling on the leaders of the Church. In 1976, therefore, President Kimball was visited in Salt Lake City by presidential hopefuls John Connally of Texas, incumbent President Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and even the chair of the American Independent Party, Tom Anderson. Significantly, the discussion in each case was not about politics but, rather, about religion.13

Shortly after Carter was inaugurated, he asked Utah Congressman Gunn McKay to arrange a meeting at the White House with President Kimball. The twenty-minute meeting took place in the Oval Office on March 11, 1977, right after President Kimball returned from an extended trip to Latin America. During the meeting President Kimball expressed his gratitude to Carter for his emphasis on protecting family life. President Carter, a devout Baptist, commented that he felt deeply about spiritual things, and said that he prayed often during the day for guidance in making decisions.14 This must have gratified President Kimball deeply.

On November 27, 1978 President Carter spoke in a program at the Salt Lake Tabernacle at the end of National Family Week. Carter had, in fact, telephoned President Kimball asking if he could speak there on the family, for he appreciated the pro-family position of the Church. “I know how much less difficult my own duties would be as president if your mammoth crusade for stable and strong families should be successful,” he said in his Tabernacle address. “That is why I feel a close kinship with you, and a partnership with you, in achieving this noble purpose. Your great church epitomizes to me what a family ought to be, a church that believes in strong families, in individualism, the right to be different, but the opportunity and even the duty to grow as a human being, to prepare oneself for greater service.”15

At the meeting President Kimball presented President Carter with a sculpture by well-known Utah sculptor Dennis Smith titled “In the Family Circle.” It depicted a young mother and father helping their toddler take her first steps. When the President was headed to his hotel after the program he suddenly stopped the motorcade and had an aide rush back to the Tabernacle to retrieve the gift instead of allowing it to be shipped as planned. “I want to show that to Rosalynn tonight,” he explained.

In 1978 President Carter took notice of President Kimball’s revelation granting the priesthood to all male members of the Church. He commended the church leader for his “compassionate prayerfulness and courage.”16

President Carter admired the Church in part because of what he knew about the missionary program, and on at least one occasion he wanted to know more. In April 1977 President Kimball and his first counselor, Marion G. Romney, visited a stake conference in Fillmore, Utah. During one of the meetings a call came from the White House. It was President Carter, asking to speak to President Kimball. Since President Kimball was at the pulpit speaking, President Romney took the call. Carter said that he was preparing to speak at a Baptist convention in Mississippi, and he wanted to talk to the group about creating a more effective missionary program, like that of the Mormons. He asked many searching questions, wanting to know such things as how many missionaries there were, who they were, what ages they were, what salary they received, how long they served, where they came from, where they were sent, and how they were selected, trained, and supervised. President Romney told him that there were about thirty thousand missionaries at the time. He also explained that missionaries were trained from childhood and that he had a four-year-old grandson already singing “I Hope They Call Me on a Mission.” He explained that missionaries paid their own expenses, which seemed to stun President Carter, that they went to all parts of the world, how they were trained, and how long they served. President Carter was deeply impressed, calling it an inspired program, and complimenting the Church on it. He also asked that additional information be sent to him.17

On May 31, 1977, the Church made a presentation to President Carter that began a tradition repeated with several U.S. President, as well as with leaders of other nations. W. Don Ladd, a Regional Representative of the Twelve, and Thomas E. Daniels of the Genealogical Department of the Church presented the American President with a two-inch thick, leather-bound volume of genealogical information on his family, along with a family tree. The accompanying letter from President Kimball referred to the Latter-day Saints’ “deep reverence and gratitude for our ancestors, which in turn gives us greater sense of responsibility to our posterity.” Carter was grateful and excited, for it gave him information about his family that he never knew.18

Jimmy Carter lost his bid for reelection in 1980. He was defeated by the popular former governor of California, Ronald Reagan, who won nearly 51 percent of the popular vote nationwide and nearly 73 percent in Utah. Reagan won again four years later with an even greater national majority and 74.5 percent of Utah’s popular vote. In that same election 85 percent of Latter-day Saints throughout the country voted for Reagan.

In a real sense, the Reagan administration represented the idea cited near the beginning of this essay, that the Church had become the “darling of the White House.” Before his election Reagan was already close to the Mormons, having made several visits to Salt Lake City and often dined with Church leaders. An active Mormon and future General Authority, Richard B. Wirthlin, was close to Reagan and helped engineer his victory in both elections. Chair of his inaugural committee was prominent LDS Washington attorney Robert W. Barker and two General Authorities were the Church’s official guests at the inaugural: President Ezra Taft Benson of the Quorum of the Twelve and Joseph B. Wirthlin of the First Quorum of the Seventy (brother of Richard B. Wirthlin).The Tabernacle Choir sang the stirring “Battle Hymn of the Republic” in his inaugural parade and it was on this occasion that President Reagan dubbed it “America’s Choir.” Popular LDS singing stars Donny and Marie Osmond also performed at various inaugural events.

Reagan’s appointments to various positions in his administration included an unusually high number of Latter-day Saints. To name just a few: David C. Fischer and Stephen M. Studdert, special assistants to the President; Richard B. Wirthlin, chief strategist; Roger B. Porter (now IBM Professor of Business and Government at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government), economic policy advisor; Utah’s Ted Bell, Secretary of Education; Angela Buchanan, Treasurer of the United States; Rex Lee (later President of BYU), Solicitor General; Brent Scocroft, chair of the commission on Strategic Forces; Richard Eyer (prominent Utah specialist on parenting and the family), director of the White House Conference on Children and Parents; Elder Thomas S. Monson of the Council of Twelve, member of the President’s Task Force on Private Sector Initiatives. The list could go on and on for, in fact, Reagan appointed more Latter-day Saints than any other President.19

In addition to knowing of such appointments, Latter-day Saints were delighted to discover that Reagan was familiar with the Book of Mormon. He even wrote to the missionary son of Utah Senator Jake Garn, quoting from the Book of Mormon.20 He also greatly admired the Church’s welfare program. He knew about it in great detail, and often praised it publicly as an ideal for the rest of the nation.

It is possible that the Latter-day Saints even influenced one important public policy decision during Reagan’s administration. Earlier the Pentagon proposed the development of a system of intercontinental ballistic missiles, known as MX. The huge missile site would be located in western Utah and eastern Nevada. Some Church leaders were concerned and, after much consideration and after receiving substantial input from University of Utah law professor Edward B. Firmage, the First Presidency issued a strongly-worded statement opposing the MX project. Among their reasons were the possibility of escalating the arms race between the United States and Russia, the fear that this area would become a primary target in case of a preemptive strike, and serious environmental concerns. The result was that the First Presidency statement tended to move public opinion, not just in Utah but elsewhere, against the project. According to one of Reagan’s biographers, the statement was a blow to the MX proposal for it ratified the view of Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger that the system faced insurmountable obstacles. Partly because of the First Presidency’s statement, Weinberger was able to convince the President that approving MX was bad politics. This was one of only a very few times that the First Presidency saw fit to make a public statement on a controversial political issue, and this time, at least, it worked.21

George H. W. Bush, Reagan’s Vice-President, won the Presidency in the election of 1988. He won not nearly as handily as Reagan, but in Utah he received 66 percent of the vote—a larger margin than in any other state.

Like many of his predecessors, Bush was familiar with the Church and some of its members before he took office, and he made it clear that he had great respect for the Mormons. He was the fourth president to invite the Tabernacle Choir to perform at his inauguration. Officially representing the Church at the inaugural were President Ezra Taft Benson and his second counselor, Thomas S. Monson. In 1989 Bush awarded the Presidential Citizens Medal to President Benson. This award, established in 1969, recognizes individuals “who [have] performed exemplary deeds or services for his or her country or fellow citizens.” Like Reagan, Bush also had several Latter-day Saints in his administration. Among them was Jon Huntsman, Jr., who served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Commerce for trade development and commerce for East Asian and Pacific Affairs. In June 1992, Huntsman was nominated by Bush to become U.S. Ambassador to Singapore and was unanimously confirmed by the Senate. At age 32, he became the youngest U.S. Ambassador in over 100 years.

President Bush served only one term, losing his 1992 bid for reelection to Governor Bill Clinton of Arkansas, who was reelected in 1996. Clinton, too, showed great respect for the Church, though he was generally unpopular in Republican-dominated Utah. Representing the Church at his inaugural was Elder James E. Faust of the Quorum of the Twelve, a Democrat.

One of the things Church leaders appreciated early in Clinton’s administration was his signing the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which had been sponsored by Utah’s Senator Orrin Hatch and in favor of which Elder Dallin H. Oaks had testified before a Congressional subcommittee. The new law helped many churches. When the President signed the bill Elder M. Russell Ballard and Senator Orrin Hatch were in attendance.22 Church leaders also appreciated the fact that the Clinton administration was careful to include the Church in various discussions and events, such as his 1992 invitation to the Church to be represented on the President’s Summit for America’s Future. Co-chair of the Committee on Faith at that summit was Elder Jeffrey R. Holland. In 1995 the Church issued its powerful “Proclamation to the World” on the family. President Clinton heard about it and invited President Gordon B. Hinckley to the White House to discuss it. During the thirty-minute meeting in the Oval Office, also attended by Elder Neal L. Maxwell, they discussed the importance of families. In addition, Clinton was presented with a volume containing Clinton’s family history. A similar volume was given to Mrs. Clinton. The President complimented the Church in several other ways, including a laudatory greeting in 1997 as the Church celebrated its pioneer sesquicentennial.

Despite Clinton’s good words about family values, his personal life reflected a different set of values, which led to his impeachment by the House of Representatives in December 1998. However, he was acquitted by the Senate the following February. Mormons in Congress had mixed reactions as to whether he should be acquitted. All thought Clinton’s immorality was reprehensible, and Representative Chris Cannon of Utah, who presented the charges to the Senate, deemed his acts worthy of removal from office. Others felt the same way, and all the LDS members of Congress from Utah voted against the President. However, Senator Harry Reid, an active Latter-day Saint from Nevada, recognized the gravity of Clinton’s straying from his marriage vows, but he believed that, under the Constitution, his actions did not constitute crimes worthy of removal from office. It took a two-thirds majority in the Senate to convict, and in a largely partisan vote this could not be obtained. The fact that the President perjured himself by lying under oath about the affair did not seem to matter. “Is it asking too much of our public servants to not only make of this nation the greatest nation on earth politically, but also to give moral leadership to the world?” President Hinckley asked when he was interviewed about the affair.

George W. Bush, son of the first President Bush, was elected in the year 2000 by a very narrow electoral vote, even though he received fewer popular votes than his Democratic opponent, Al Gore. He remained in office for two terms. As might be expected, in the year 2000 Utahns gave him 66.8 percent of their votes, a larger percent than any state but two. In the next election they gave him a larger percent than any other state, 72.7. Nationwide, one study showed that 88 percent of the Mormons supported him in 2004.23

Bush and the Mormons got along famously even though, as some who were close to him have noted, he did not know much about them before he got into office. The Tabernacle Choir sang at his inaugural in January 2001. In September of that year he invited President Gordon B. Hinckley to join with other religious leaders in a special White House meeting. In February 2002, while President Bush and his wife Laura were in Salt Lake City for the Olympic Games, the First Presidency presented them with copies of their family histories—something that was becoming traditional for American presidents. After the terrorist attack on the New York World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, President Gordon B. Hinckley was one of twenty-six religious leaders invited to meet with President Bush in the White House. There they listened to the President’s concerns, offered advice, and prayed with him. On June 23, 2004, President Bush awarded to President Hinckley the Presidential Medal of Freedom—the nation’s highest civilian honor.24 In 2006 Elder Russell M. Nelson of the Quorum of the Twelve met with President Bush to express the Church’s support for an amendment to the Constitution banning gay marriage. When President Bush called on Congress to pass the amendment, Elder Nelson, along with other religious leaders, was standing with him. However, that amendment has never passed.

As in the case of many presidents since the beginning of the 20th century, Bush had several Mormons in his administration. On March 28, 2001, he appointed Jon Huntsman, Jr. to be one of two Deputy United States Trade Representatives. Governor Mike Leavitt of Utah became head of the Environmental Protection Agency in November 2003. In December 2004 he was appointed to the cabinet position of Secretary of Health and Human Services. There were other Latter-day Saints appointed to various other positions.

It appears that, in general, the majority of Mormons supported Bush through both of his administrations, though many very active Church members disagreed with his politics and worked against him. During his bid for reelection in 2004 a thousand Utah students, mostly Mormon, helped the campaign in the so-called “battlefront states.” Besides Bush’s personal popularity among them, some have suggested that Mormons supported Bush in 2004 because of the stand of his opponent, John Kerry, in favor of abortion rights, civil unions, and other such “hot issues.”

Bush was popular among the Mormons, but it was just the opposite with his successor, Democrat Barak Obama. In the 2008 election Obama received a national popular vote of 52.9 percent to 45.6 percent for his Republican opponent John McCain. In Utah, however, Obama received only 34.2 percent of the vote while McCain got 62.2 percent. Four years later, with Mitt Romney, a Mormon, as the Republican candidate, Utah gave Obama only 24.7 % of its vote while Romney garnered 72.6 percent. Nationally the popular vote was 47.2 percent for Romney and 51 percent for Obama. Interestingly enough, however, a national poll by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life showed that more Mormons voted for Bush in 2004 than for Romney in 2012: 80 percent for Bush and 19 percent for John Kerry in 2004 to 78 percent for Romney and 21 percent for Obama in 2012. (Figures for 2008 were not available.)25 But despite the still somewhat overwhelming opposition to Obama among the Mormons, it must be observed that 21 percent is not insignificant. Numerous blogs, twitters, emails and even a few websites resulted from a significant Mormons for Obama movement,26 all of which was probably very good so far as Church leaders were concerned, for it showed that Mormons were not locked into a particular political stance because of their religion.

As Obama assumed office in 2009, Church leaders studiously maintained their political neutrality and did all they could to establish good relations with him. On July 20, just over six months after the inauguration, President Thomas S. Monson and Elder Dallin H. Oaks met with Obama in the White House. At the meeting, which was arranged by Senator Harry Reid, the Church leaders presented the President with five large, leather-bound volumes of family history and a table-long pedigree chart. “President Obama's heritage is rich with examples of leadership, sacrifice and service,” President Monson said. “We were very pleased to research his family history and are honored to present it to him today.” President Obama said “I enjoyed my meeting with President Monson and Elder Oaks. I'm grateful for the genealogical records that they brought with them and am looking forward to reading through the materials with my daughters. It's something our family will treasure for years to come.” 27Such presentations were becoming traditional, but this was unusually early in the President’s administration. The meeting was very cordial, and certainly a sign of mutual respect.

In May 2009 Obama appointed Utah’s Republican governor Jon Huntsman, Jr. as U.S. Ambassador to China. Huntsman had learned Mandarin Chinese while on an LDS mission in Taiwan. As noted earlier, he had a great deal of previous experience in federal appointments. He had also become one of the best-known Republican governors in the nation. Huntsman resigned at the end of April 2011 and the following year vied with Mitt Romney and others for the Republican presidential nomination.

As Obama’s first term proceeded, the all-Mormon Utah Congressional delegation, including, at times, its one Democrat in the House of Representatives (Jim Matheson), continued to oppose much if not most of Obama’s legislative initiatives. On the crucial “fiscal cliff” vote, delayed until January 1, 2013, only Senator Orrin Hatch was willing to compromise and vote for the deal brokered by Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and Vice President Joe Biden. But that is the way politics seem to work.

The presidential campaign year of 2012 has sometimes been dubbed the “Mormon moment,” for that year it appeared that the Mormons might actually see one of their number elected President of the United States. Mitt Romney was the son of George Romney, who tried unsuccessfully for the Republican nomination in 1968. Mitt Romney had been an LDS bishop and stake president and, from 2003-2007, governor of Massachusetts. He was also a highly successful businessman. In 2008 he ran for the Republican presidential nomination but lost, partly because of the bias and suspicion against Mormons that still existed, especially among evangelical Christians, and partly because, politically, he seemed to change his mind on issues and was dubbed a “flip-flopper.” The last charge did not change in 2012, but the extremes of anti-Mormonism had changed. In fact, even though Romney lost the campaign, the Church received more positive publicity during that year than in almost any other time in its history. In that sense, even the loss of the presidency by one of its members was a major boost to the Church.

As soon as the 2012 election results were clear, the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve issued a press release congratulating the re-elected president. They also invited Latter-day Saints to pray for Obama and other national leaders. “After a long campaign, this is now a time for Americans to come together,” the statement said. “It is a long tradition among Latter-day Saints to pray for our national leaders in our personal prayers and in our congregations. We invite Americans everywhere, whatever their political persuasion, to pray for the President, for his administration and the new Congress as they lead us through difficult and turbulent times.” Romney, too, prayed for the President. “This is a time of great challenges for America,” he said in his concession speech, “and I pray that the president will be successful in guiding our nation.” Obama also struck a positive, conciliatory note in his acceptance speech. To those who voted for Romney he said “...whether I earned your vote or not, I have listened to you, I have learned from you, and you've made me a better president. And with your stories and your struggles, I return to the White House more determined and more inspired than ever about the work there is to do and the future that lies ahead.”28

In conclusion, I think it is appropriate to remind ourselves again that, despite apparent LDS leanings toward the Republican Party throughout the century, there has been and still is a healthy diversity of political opinion among Church leaders. This certainly sets the tone for an important ideal that I believe should characterize the thinking of all Church members. Men and women of good will can be unified in things religious while at the same time they may disagree in political philosophy without calling into question the loyalty, integrity, or faith of those with whom they disagree politically. Church leaders have constantly set that example and have also publicly urged members to vote their own convictions.

In the “Newsroom” section of the official Church website, www.lds.org, there is an extensive statement on political neutrality. It concludes with this important sentence: “In the United States, where nearly half of the world’s Latter-day Saints live, it is customary for the Church at each national election to issue a letter to be read to all congregations encouraging its members to vote, but emphasizing the Church’s neutrality in partisan political matters.”

In 2012 that letter, signed by the First Presidency, read, in part, as follows:

As citizens we have the privilege and duty of electing office holders and influencing public policy. Participation in the political process affects our communities and nation today and in the future.

Latter-day Saints as citizens are to seek out and then uphold leaders who will act with integrity and are wise, good, and honest. Principles compatible with the gospel may be found in various political parties.

Therefore, in this election year, we urge you to register to vote, to study the issues and candidates carefully and prayerfully, and then to vote for and actively support those you believe will most nearly carry out your ideas of good government.

Certainly members of the Church in all political parties can subscribe to this important council.

ENDNOTES

1. As in the case of part I, some of this article is drawn (sometimes verbatim) from an article I published a little over thirty years ago. See James B. Allen, “The American Presidency and the Mormons,” Ensign (October 1972), 36-56. Much of the rest is based on Michael K. Winder remarkably well-done study, Presidents and Prophets; The Story of American’s President and the LDS Church (American Fork, Utah: Covenant Communications, 2007).

2. D. Michael Quinn, The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1994), ix.

3. For a discussion of the Smoot hearings see Harvard S. Heath, “The Reed Smoot Hearings: A Quest for Legitimacy,” Journal of Mormon History 33:2 (Summer 2007), 1-80.

4. As quoted in B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church (Salt Lake City: Published by the Church, 1930) 6:436.

5. Improvement Era 15 (October 1912), 1120–21.

6. For a discussion of the League of Nation controversy in Utah, see James B. Allen, “Personal Faith and Public Policy: Some Timely Observations on the League of Nations Controversy in Utah," BYU Studies 14 (Autumn, 1973): 77-98. Reprinted in James B. Allen and John W. Welch, eds., Life in Utah: Centennial Selections from BYU Studies (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 1996): 271-94.

7. Winder, Presidents and Prophets, 253. In addition to the portion of the letter quoted by Winder, Roosevelt added another most in the last paragraph. He indicated that the incident he mentioned happened when he was a “small boy,” suggesting he may have been around 10 years old. He was born in 1882, so the incident may have occurred around 1892. The Manifesto, issued in 1890, forbad further plural marriages, but earlier marriages were still resulting in children to plural wives. The story, as rehearsed by Roosevelt, was as follows: “ However, I shall never forget a stop, which my Father and Mother made in Salt Lake City, when I was a very small boy. They were walking up and down the station platform and saw two young ladies each wheeling a baby carriage with youngsters in them, each about one year old. My Father asked them if they were waiting for somebody and they replied ‘Yes, we are waiting for our husband. He is the engineer of this train’. Perhaps this was the origin of the Good Neighbor policy.” Found online at http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/psf/box37/t335b01.html.

8. Conference Report, October 1952, 129–30.

9. Winder, Presidents and Prophets, 269.

10. Deseret News, October 28, 1960. For an interesting discussion of President McKay’s endorsement of Nixon and the public reaction, as well as general Mormon attitudes in that era, see Dean E. Mann, “Mormon Attitudes Toward the Political Roles of Church Leaders,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 2:2 (1967): 32-48.

11 . See Arnold K. Garr, “Republican Party,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-Day Saint History, ed. Donald Q. Cannon (Salt Lake City, Deseret Book, 2000), 1004; Stephen J. Bahr, “Social Characteristics,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1992), 1375-76.

12. Commencement address, Brigham Young University, May 31, 1968.

13. Edward L. Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride The Presidency of Spencer W. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 14.

14. “This week in Church history: 25 Years Ago,” Church News, March 23, 2002.

15. As quoted in Winder, Presidents and Prophets, 341.

16. “News of the Church,” Ensign (August 1978), 78.

17. See Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride, 121; Winder, Presidents and Prophets, 338-40; F. Burton Howard, Marion G. Romney: His Life and Faith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1988), 236; Heidi Swinton, In the Company of Prophets (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1993), 101-2. These different source have the meeting taking place in different places: Fillmore and Richfield. Kimball says Fillmore and since he was the Prophet’s son I thought he might have the best information.

18. “Church Gives Genealogy to President Jimmy Carter,” Ensign (August 1977), 79.

19. See Stephen M. Studdert, “President Reagan respected Church,” Church News, June 12, 2004; Winder, Presidents and Prophets, 351-53.

20. Winder, Presidents and Prophets, 346-50, has a long, very interesting section on Reagan and the Book of Mormon.

21. Ibid., 357, citing Reagan’s biographer, Lou Cannon, as well as Senator Orin Hatch. For the story of the origin of the First Presidency statement, see Jacob W. Olmstead, “The Mormon Hierarchy and the MX,” Journal of Mormon History 33: 3 (Fall 2007), 1-30.

22. “New Law Prohibits Unfair Zoning Decisions,” Church News, September 30, 2000.

23. See Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, “How the Faithful Voted: 2012 Preliminary Analysis,” November 7, 2012, online at http://www.pewforum.org/Politics-and-Elections/How-the-Faithful-Voted-2012-Preliminary-Exit-Poll-Analysis.aspx.

24. The Presidential Medal of Freedom, America's highest civilian award, recognizes exceptional meritorious service. It was created by President Harry S. Truman in 1945 as a recognition of notable service in war. It was reintroduced by President Kennedy in 1963 as an honor for distinguished peacetime civilian service. Precisely how many medals have been awarded is not clear, but at least sixteen were awarded in 2004. Infoplease.com http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0002285.html#ixzz2HvFwMSUz. At least one sources says that the total number of recipients exceeds 20,000. http://www.nndb.com/honors/482/000045347/.

26. See, for example, www.mormonsforobama.org.

27. “President Monson meets with Obama,” Deseret News, July 21, 2009.

28. “Mormon leaders congratulate Obama, urge members to pray for him.” Deseret News, November 7, 2012.

| Copyright © 2024 by James B. Allen | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |