| Print | Back |  |

February 4, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art Louvre Heist: Picasso's Hot Headsby Lawrence Jeppson |

One of Pablo Picasso’s most important paintings was partially inspired by two primitive busts blithely stolen from the reserves of the Louvre museum.

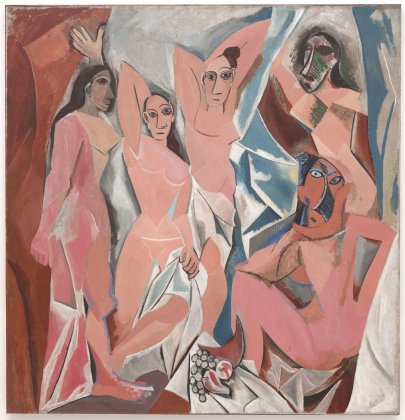

This painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, was not only critical to Picasso’s career, it launched one of the most important movements in modern art, Cubism.

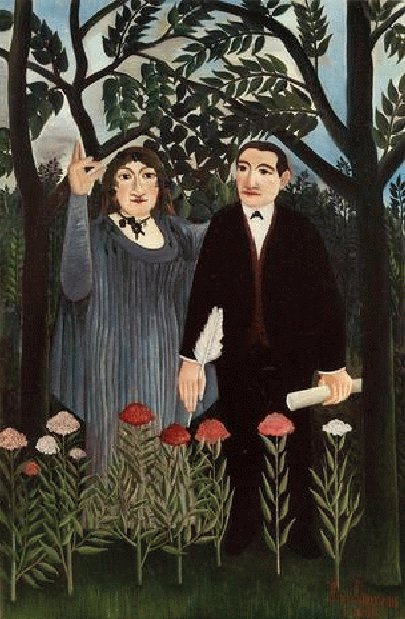

Paris has always attracted free spirits. One of them was Guglielmo Apolinari Kostrowitsky, who became known as the famous French Symbolist poet, critique, and dramatist Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918). A Russian, he was born in Rome to a Polish mother, schooled in Monaco, Cannes, and Nice, and followed his mother to Paris, where she lived with her lover, a notorious gambler.

For a brief period Apollinaire employed a secretary, a wandering Belgian named Gary Pieret. Pieret had trudged through every country in Europe, as well as the United States and Canada. In Paris he lived off the Salvation Army. He went to work for a small publication that gave advice to investors, until he was fired for trying to blackmail its publisher.

One day in 1907 he said to painter Marie Laurencin (1883-1956), who was Apollinaire’s mistress, “I’m going to the Louvre. Can I bring you anything you need?”

Pieret drifted into a gallery of Asian antiquities watched over by a single guard, who appeared to be asleep. He notice a half-open door, went through it, and discovered a storeroom filled with Egyptian artifacts. It was one of a maze of linked storerooms. “It was at that moment that I suddenly realized how easy it would be to pick up and take almost any object of moderate size.”

He selected a head of Iberian origin, a woman with twisted conical forms on her head. He put the statue under his overcoat and walked out. He sold the head to Picasso for 50 francs, which he drank that night, and went back to the Louvre the next day. There he swiped a statue of a man with enormous ears. Picasso bought that one also.

Picasso, warned by the thief not to tell anyone where the statues came from, found the two pieces enchanting and studied their primitive beauty incessantly. In 1915, long after the theft, Apollinaire wrote a friend, “I tried, long before 1911, to persuade Picasso to give the statues back to the Louvre, but he was absorbed in their esthetic studies, and indeed from them Cubism was born.”

In 1911 Apollinaire wrote the preface for the first Cubist exposition held outside Paris, the VIII Salon des Indépendants, Bruxelles.

Pieret drifted to Mexico briefly before returning to France with his pocket full of money, which he quickly lost at the races. Apollinaire took him back, but Pieret had the idea of making his own art collection from pieces he would steal from the Louvre. When he stole another statue, Apollinaire dismissed him, took him to the Gare de Lyon, and bought him a one-way ticket to Marseilles. The date was August 21, 1911, the same day that the Louvre was robbed of the Mona Lisa.

The greatest theft in Louvre history brought an avalanche of investigations, new security provisions, and inventories of holdings. Picasso and Apollinaire were terrified. If discovered, the stolen statues could incriminate them as thieves of the Leonardo da Vinci masterpiece. They were certain Pieret had stolen the Mona Lisa, which made their position even more untenable.

When The Paris-Journal offered 50,000 francs for the return of the painting, Pieret sent a letter to the paper through another party offering to sell back a head stolen from the Louvre. In returning the third head to the newspaper, he admitted he had stolen two others and that he had sold them to “painter x,” a friend.

Fernand Olivier, Picasso’s mistress at the time, later recalled, “I can see them now, contrite children, stunned by fear and making plans to leave the country.”

They decided not to flee but throw the statues in the Seine. At midnight they eased out into the black Paris night, each with a suitcase carrying a stolen head. They wandered up and down the streets for two hours but dared not act. They were certain they were being followed.

The following morning, one of them – each of them said it was the other – returned the stolen statues to the Paris-Journal in return for a promise of anonymity. The newspaper had a field day with the stories, particularly after the Louvre admitted that the three statues did indeed come from their collection of 500,000 objects and no one knew they were missing.

Investigators picked up the trail. Two policemen from the Surété raided Apollinaire’s apartment. They found incriminating letters from Pieret and took the poet into custody for harboring one of the gang who stole the Mona Lisa. A trembling Apollinaire was freed from jail after he testified that he and Pieret were together the night of the big theft. Even so, some suspicion remained, and Apollinaire became unjustly famous – in satirical song and stage jest– to the public as the man who hoisted the Mona Lisa.

Fernande Olivier said that both men broke down and wept before the judge, who “had some difficulty maintaining his judicial severity in the face of their childish grief.”

Picasso did not admit his complicity until 48 years later.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |