| Print | Back |  |

January 28, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art Chalk Up Another for Avardby Lawrence Jeppson |

Towards the end of any appraisal I wrote about a sculpture by Avard Fairbanks I always included this line: “I first met Avard Fairbanks personally in October, 1948, when I witnessed a prodigious demonstration of his monumental drawing skills.”

In the appraisals I never explained that statement.

Earlier in that October I had taken the night bus from Reno back to Salt Lake City a week or so before entering the Mission Home. Alice Cannon invited me to go with her for the Sunday farewell of a friend, another elder who was going to France, Justin Fairbanks. That began a cherished friendship that lasted until Justin’s death a few years ago.

There were six of us going to France to begin our 2 ½ year service under President James L. Barker. There were elders in the Mission Home who were going to Holland and other places, enough of us so that leaving Salt Lake we had our exclusive railway car, at least until we changed trains in Chicago.

As usual on departure day, there were squads of friends and family clustered on the quai to say farewells, among them Avard Fairbanks, Justin’s father, and I don’t know how many more of that clan.

On the outside of passenger cars there is a considerable open distance between the bottom of the windows and the top of the undercarriage. Avard brought with him a supply of chalk, and he lost no time filling that space with cartoons of a phalanx of missionaries and inscriptions in English and French like, “Mormon missionaries to France. Here we come.” As the train sped along, anyone seeing it from the graffiti side would know instantly whom it carried.

On several occasions in later decades I heard Avard lecture on his art and philosophy of sculpture while demonstrating his techniques and abilities, using what he called his "gifted thumbs." These demonstrations remain choice memories.

Born in Provo, Utah, Fairbanks was the tenth son of a well-known pioneer artist, JB Fairbanks, whom I wrote about two weeks ago. After his mother died, he and his father moved to Salt Lake City, where an older sister, Nettie, helped raise him. In the third grade he evidenced an intense interest in drawing. His older (by 19 years) brother J. Leo Fairbanks (1878-1946) was art supervisor in the county schools. By the time Avard reached the sixth grade he was modeling in clay. Leo took private students, and one summer day Avard said to his brother that he could do better than a particular student in drawing and modeling. Leo’s reply was, “All right, go ahead, let’s see if you can.”

Avard’s sketches were not better; so he turned to modeling. He took a pet rabbit out of its cage and modeled her at one-quarter scale. It was a piece of good work, but the casting was unsuccessful. He started over, modeling the rabbit at one-half scale. The casting was successful and the bronze bunny was publicly exhibited.

In June, 1909, JB took twelve-year-old Avard with him to New York, where the father was making copies of famous paintings in the Metropolitan Museum. (The copies were selling better than the artist’s originals.) Not wanting the boy to run around loose in New York, JB asked the Met to allow Avard copying privileges. Despite the answer that, “We can’t have children around here,” the request was granted, and soon Avard was copying Lion and Serpent by Antoine Louis Barye (1796-1875), the most formidable sculptor of animals of the 19th century.

A lad of twelve working in the museum soon attracted crowds. The museum director apologized to JB for being incredulous when the copying request was made. A reporter for The New York Herald eventually stumbled onto the scene and returned with a photographer. As soon as the paper began telling its readers about the boy, the rest of the press followed.

Avard soon became a familiar figure at the Bronx Zoo, where he sculpted models of the animals. He was befriended by Zoo Director Dr. William Temple Hornaday (1854-1937), a naturalist and animal writer of world-wide fame. The New York papers described Hornaday as “the young Fairbanks’s steadfast patron, showing him every kindness and appreciation of his work, and says the next house he builds will be for the Fairbanks animal collection.” (Quoted by The Herald-Republican, July 2, 1911.)

Four days later The Salt Lake Tribune picked up the story, added a picture of the young sculptor with one of his animals standing in front of an exhibition showcase filled with other small statues. It warned that if Dr. Hornaday wanted Avard’s animals he had better move quickly because a Fifth Avenue art dealer had made overtures to cast the animals in bronze. The Tribune mentions Avard’s having completed a model of a polar bear, Silver King, in addition to The Fighting Puma and Ivan, the Alaskan bear.

Another newspaper clipping, with the headline “Boy Sculptor Wins Scholarships for His Animal Reproductions,” shows Avard posing with Dr. Hornaday and a zoo guard in front of Ivan the Bear’s cage. Ivan is on his hind legs looking at them–and perhaps also at the model of Ivan, which sits on a high, narrow stand between Avard and the other men. It’s a delightful old photo.

The boy heard rumors through the press that Leo was going to take him to Europe to study, but that did not happen that year nor the next. Avard wrote Leo that he would introduce him to Gutzon Borglum (1867-1941), Proctor, Frazer and others if he would visit him in New York.

Back West his sculpture carried off virtually all the prizes at the Utah State Fair.

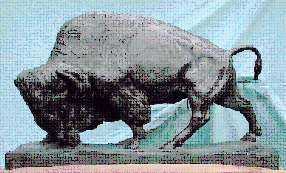

When Avard was 13, one of his pumas was accepted for the exhibition of the National Academy of Design, and he was accepted again the next year with a piece referred to at the time as The Bull but which is actually Buffalo Charging. No surprise, it was exhibited in Buffalo, NY. Its quality gave his career a substantial boost.

The time young Avard spent at the Bronx Zoo modeling his animals was part of a demanding routine. He did not want to fall behind in his class studies back in Salt Lake. He and his father were living in New Jersey and commuting. Avard would leave home at 8:00 A.M., study while riding on the train, spend the day at either the Met or the Zoo, study nights at the Art League, and get home around midnight.

A piece that won him wide recognition was a bas relief showing Hiawatha learning “from every bird its language,” based on the Longfellow poem. Published by a New York company, “this fine bit of work is finding its way to all parts of the country.” (Young Woman’s Journal)

Art Historian William Bridges in Gathering of Animals, Harper and Row, 1966, quotes the experience of Paul Branson, an illustrator who recalled his time at the Zoo:

Mr. Frederick G. R. Roth had a locker in the room, (designed to draw and model animals at the opposite end of the building) but he always did his work out in the main Lion House (where the light was on the animal). Mr. Roth was (in my opinion) the finest animal sculptor America has produced. The only other artist in constant attendance whom I can recall at the moment was a lad in knee breeches named Alvord [sic] Fairbanks. He was always quietly drawing somewhere around the Park. I tried to make his acquaintance, but he was a “loner” and shied away from all attempts to become acquainted (Fairbanks was a fourteen-year-old prodigy from Utah who won a scholarship from the Art Students’ League for his model of Sultan, the lion.)

A biography of young Avard which appeared in 1914 in Young Women’s Journal begins saying:

In years to come when the question shall be asked, “What men and women of genius have been given to the world by Utah and “Mormonism?” the list submitted in answer will contain the name of Avard Fairbanks, Utah’s boy-sculptor. This prediction is based on the work that he has already accomplished, the spirit he possesses of desire and determination to excel, and the helpful encouragement of his father and brother–both artists–who refuse to permit the lad’s native ability to remain undeveloped. If Avard does not attain to greatness it will be because of circumstances that are now wholly unforseen.

It is well-known that the boy’s father was an important pioneer artist, from whom Avard inherited artistic gift and encouragement. Less well known is the fact that Avard’s mother, Lillie, who died from a fall when Avard was one, had a flair for modeling three-dimensional articles. She would combine sand, earth, pebbles, brush, grass, and twigs and, using small mirrors to represent lakes and brooks, would model miniature landscapes that won a number of diplomas and other awards at the state fair. She designed wreaths from seeds and flowers. When she finished her weekly churning, she would sculpt the butter into birds and animals. One readily foresees the boy in the Bronx Zoo.

Avard’s adult ventures and accomplishments are for later columns.

| Copyright © 2025 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |