| Print | Back |  |

January 21, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art The Hahn-Duveen Tumultby Lawrence Jeppson |

A few months before the Great Depression ripped asunder the rampaging American economic fabric, the art world was hit by a sensational trial that threatened to strike down the all-time king of picture dealers, Sir Joseph Duveen. His reputation and resources were so great he could call upon the backing of the Bank of England.

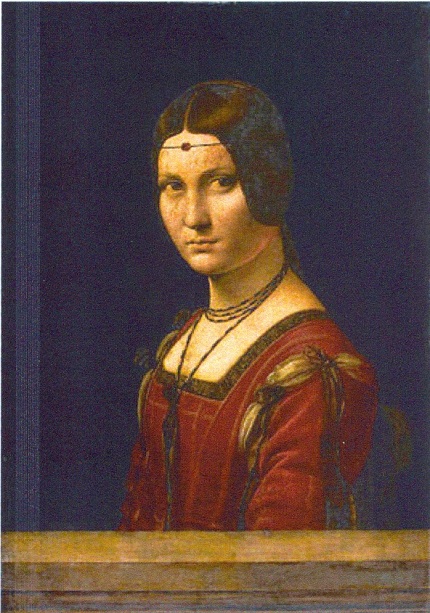

The heart of the dispute was a painting claimed to be by Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), La Belle Ferronnière, owned by a couple from Kansas and declared by Duveen to be a fake.

One of their ploys was to discredit Duveen.

In the course of endless litigation, the respected and independent Art Digest, through whose page one looks in vain for Duveen advertising, predicted on “infallible authority” that the plaintiffs were prepared to produce a certain unknown painter who would swear “he painted at least 20 pictures that had passed into the collections of leading American connoisseurs and museums as works of immortal old masters fully authenticated by [Duveen’s] experts.”

The debacle actually began in 1920.

Mrs. Harry J. Hahn was a French girl who had wed an American army officer and settled with him in Junction City, Kansas, where he owned an automobile business. It was quite a coup that this moon-faced, optimistic, and perpetually smiling Midwesterner could take the heart of this stolid Breton lady with titled relatives.

When the Hahns married, Andrée’s godmother gave her a painting called La Belle Ferronnière, a full-face portrait of a woman which the family had always attributed to da Vinci.

In 1920 the Hahns, through a quiet Kansas City dealer and friend, Conrad Hug, 51, were negotiating to sell the painting to the Kansas City Art Institute for $250,000. Its museum had been given $15 million by Kansas City Star tycoon William Rockhill Nelson uniquely for acquisitions.

The painting had been authenticated in 1916 as a genuine da Vinci by Georges Sortais, an expert of 40 years standing accredited to the Paris courts.

On June 18, 1920, Sir Joseph Duveen pontificated to a reporter from the New York World: “The Hahn painting is a copy, hundreds of which have been made. The real Belle Ferronnière is in the Louvre.”

As seen by H. H. Pars, Pictures in Peril, Duveen “was ruthless and arrogant to the extreme and unscrupulously set against all competitors.” Since he did not own the Hahn painting, he could not sell it. This made Andrée Hahn and Conrad Hug his business rivals. His denunciation to the newspaper was a stick of dynamite that blew Mrs. Hahn’s sale to dust.

She brought suit for $500,000 in damages.

When Duveen made his statement, he had not seen the Hahn painting – not even a photograph of it. He was, furthermore, on record as believing the Louvre Ferronnière, catalog number 1600, was NOT a Leonardo.

In strange contradiction to his statement to the reporter, two months later – August 5, 1920 – Duveen wrote to his London manager, “The Louvre painting is not passed by the most eminent connoisseurs as having been painted by Leonardo da Vinci, and I say I am entirely in accord with their position.”

Yet in the trial he said, “I told you I have never changed my mind about the authorship of the Louvre picture.” (A clear case of perjury.) He also said he had never been taken in by a fake picture.

Court: “Did you know whether Leonardo painted the [Louvre] painting or not?”

Duveen: “Of course it was my opinion that he painted it. Yes, certainly, I know he painted the picture.”

There is no question that Duveen was the most powerful art dealer of the time. His handling of Andrew Mellon is legendary. (A subject for a future column.) Probably he had been threatened by legal actions before, but only two of these went to formal filings. The first plaintiff, Edgar Gore, went down with the Lusitania. That ended the litigation. The second, Georges Demotte, a Paris dealer, dared to open a competitive gallery in New York. Demotte sold a 13th century Virgin and Child. Duveen declared it a fake and said he would “spend $500,000 to prove it and oblige Demotte to leave New York.” Demotte sued–but died in a hunting accident in Normandy.

Duveen had the power and lawyers to get the Hahn trial repeatedly delayed for nearly a decade. The Hahns used the time to search French archives to trace the provenance of their picture. Duveen countered with the testimonies of ten big-league experts. They were often at odds with each other. Duveen himself was kept on the stand for five punishing days.

The jury, selected for its ignorance of art, heard four weeks of testimony, saw hundreds of photographs, studied innumerable x-ray negatives, and were told many secrets of the art business. Records of the trial filled six ponderous volumes. Trial Judge Black said to the jury, “You have been privileged to sit in on one of the most interesting cases every tried in my court.”

To win, Hahn had to prove her picture was a genuine Leonardo and that Duveen’s statement had been inspired by malicious intent.

The jury came in at 5:00 a.m., March 2, 1929, after 15 hours of deliberations.

They could not reach a verdict. The count stood at 10 to 2 against Duveen. After the trail, the two dissenters would not discuss it. Later it turned out that one of the two was an employee of J. Pierpont Morgan, a big Duveen customer.

For the retrial, Duveen hired the most famous criminal lawyer in New York. The Hahn lawyers would try to place before the jury that Duveen Brothers had been adjudged by the federal government guilty of smuggling and paid a fine of more than a million dollars to the U.S. Treasury.

The strain of the first trial hastened the death by cancer of Conrad Hug.

At the eleventh hour the second trial was settled out of court. Duveen did not acknowledge the authenticity of the Hahn painting, but the fact that he and some of his experts had challenged it made its sale at a da Vinci price difficult.

Harry Hahn had to rescue the reputation of his wife’s painting, or it would be forever “burned,” as the art trade says. He continued his research in France. In 1946 he published all his findings and arguments in The Rape of La Belle, a study in conspiracy theory.

About a decade ago a friend of mine tracked down the picture. She said it was still (again?) for sale. I don’t recall the price. It had been in an Omaha bank for decades.

In January of 2010 La Belle Ferronnière went on a Sotheby’s auction block as being by a follower of da Vinci. It brought a hammer price of $1.5 million, three times the high pre-sale estimate.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |