| Print | Back |  |

January 21, 2013 |

|

Rambling Thoughts on Church History The American Presidency and the Mormons Part I: The 19th Centuryby James B. Allen |

Last November, for the fifty-seventh time in their history, campaign-weary American voters completed the momentous task of choosing a president. For well over a year they had been deluged with ever larger doses of political propaganda and campaign oratory, but come November 7 the contest was decided, Barack Obama was elected to a second term, and the furor temporarily subsided. One thing that made this election especially memorable for Latter-day Saints is that this was the first time one of their number had been nominated by one of the major parties. Mitt Romney took his defeat graciously but, as in all previous elections, members of the defeated party would soon begin formulating battle plans for taking over the White House in another four years.

American Latter-day Saints naturally take special interest in presidential elections. We believe that the U.S. Constitution is divinely inspired and that the American nation has a special destiny. We are concerned, therefore, that the electoral process bring to the highest office in the land wise men who support the principles of the Constitution, who are capable administrators, and who are men or women of integrity. What follows is an attempt to add a bit of historical perspective by suggesting highlights of past elections, attitudes toward them taken by Latter-day Saint leaders, and Mormon relationships the Presidents. It will be done in two parts.

America’s electoral college, created by the framers of the Constitution, is a unique system for electing the chief executive. It was actually an attempt to keep the selection out of the hands of the masses, for the framers tended to fear the consequences. They wanted the ultimate decision to be made by a few well-selected people, hoped to allow Congress some limited participation in the selection, and wanted to recognize the role of the states as sovereign bodies in the new federal system. That is why the Constitution provided that each state should choose a number of electors equal to its total representation in Congress (thus giving small states a slightly disproportional representation because of the fact that every state has two senators).

The electors each voted for two persons. The candidate with the greatest number of votes became president and the one with the next highest became vice president. If no person had a majority, the House of Representatives chose the president and vice president. In that instance, however, each state had only one vote in the process. By thus shielding the electoral process from the whims of the people at large, the founders hoped to provide the best means for choosing the men most fit to be president. This system does not necessarily reflect majority opinion; in at least fifteen out of forty-six elections, the victor has won with less than 50 percent of the popular vote.

However, the electoral college did not work exactly as the founders conceived it, and for several reasons. First, they did not anticipate the rise of political parties or the serious administrative and political problems that might arise if the president and vice president held radically different political philosophies. After such an experience when John Adams was president and Thomas Jefferson was vice president, the Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution was adopted in 1804, requiring that electors cast their ballots separately for president and vice president. For all practical purposes this amendment recognized the existence of parties, for since that time the candidates have run as teams. Second, Congress has not played even the limited role apparently anticipated by some of the founders, for only on two occasions has the election been thrown to the House of Representatives.

Third, the electoral college itself no longer has the power originally anticipated for it. At first it was not mandatory that the electors be chosen by popular ballot or that they be committed to any candidate, and after their election the campaign often continued up to the day the electors met to cast their ballots. Today, the voters of each state choose electors already pledged to vote for specific candidates, which means that for all practical purposes the choice is made at the polls in November rather than at the casting of the electors’ ballots when the electoral college meets in December. The law does not require electors to honor their pledges, and on several occasions some have reneged and voted for another candidate. However, this has changed an election only once in our history.2

By the way, the term “electoral college” was not used by the Founders. It came into use only gradually, and was written into federal law only in 1845.

In 2012 the electoral college consisted of 538 electors, based on their being 435 members of the House of Representatives, 100 senators, and three electors from the District of Columbia.

Perhaps the only semblance of the founders’ intent still preserved in the electoral system is the fact that the final tally is made on the basis of states rather than popular vote, thus helping preserve the identity of states as sovereign political units.

The electoral college has come under constant attack, and in recent years nearly every election has been followed by demands for change. But since those who advocate change are so far from united on the extent and nature of what they want, and since there is little, if any, evidence that basic changes would result in better presidential leadership, it is doubtful that any dramatic innovation will be made anytime soon.

The result of America’s first presidential election was a surprise to no one. The popular vote3 took place between December 15, 1788 and January 10, 1789, and on February 4 the 69 electors cast their votes unanimously for George Washington. By 1792 philosophical differences among America’s political leaders were becoming apparent, as Thomas Jefferson and his followers were becoming a vocal opposition party. Nevertheless Washington again received the vote of every elector.

By 1796 political parties were clearly emerging. George Washington’s Federalist party had accepted Alexander Hamilton’s policy calling for federal funding of certain state debts, a federally supported bank, federal aid to manufacturers through a tariff system, and other programs that tended to enlarge the sphere of federal activity far beyond anything that Thomas Jefferson’s more democratic Republican party considered either right or constitutional. That year, however, the major issue was foreign affairs, and Washington’s Federalist Vice President, John Adams, was elected president with 71 electoral votes. Thomas Jefferson, however, received 68 votes and became Vice President. In 1800 Jefferson defeated Adams, largely on the basis of a campaign against the unpopular Alien and Sedition acts, as well as the general effectiveness of the Republicans in denouncing Federalist philosophy.

Jefferson also won the next election, and his two close friends from Virginia, James Madison and James Monroe, each followed with two terms as president. But the whimsical, transitory nature of politics was revealed when the program carried out by Jefferson and his successors included expansion of American territorial holdings, federal promotion of internal improvements (roads and canals to connect the East with the West), promotion of a national bank, and other things that extended the influence of the federal government even more than the Federalists had anticipated, so much so that the Republicans were accused of “out-federalizing the Federalists.” In 1824 John Quincy Adams became the last of the Jeffersonian Republican party to be elected.

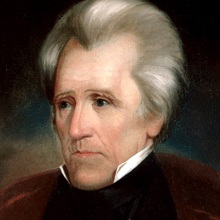

New party alignments were apparent by 1828, based partly on sectional interests and partly on personality cults; and Andrew Jackson, military hero, Indian fighter, and symbol of the “common man,” overwhelmingly defeated Adams.

The election of 1832 was the first presidential election after the organization of the Church in 1830. The chief issue in the campaign was the national bank, which President Jackson had just practically destroyed by vetoing a re-charter bill. Jackson won the election handily. It is not clear how the Saints might have voted that year, but if they voted like other Americans about 55 percent favored Jackson over his opponent, Henry Clay.

Jackson’s handpicked successor was Martin Van Buren, who won the 1836 election. At first the Saints seemingly had no strong feelings against him, but the events of the next four years completely changed their attitudes.

The main body of the Saints was in Missouri, where they were bitterly persecuted and finally driven brutally from the state. Failing to convince the courts that the state should compensate them for property lost, they turned to the federal government. However, Joseph Smith did not lose hope in the Constitution, and his feeling that it required the federal government to somehow intervene in Missouri. Even if the federal government could not intervene militarily in Missouri (as the Saints had requested in 1834), he believed that at least it had a constitutional responsibility to provide financial redress. Even this request, however, had subtle states’ rights implications that would cause this effort to fail.

In preparation for a visit to the nation’s capital, Joseph Smith asked the Saints to prepare statements and affidavits detailing their Missouri suffering and losses. As a result, beginning in December 1839, hundreds of affidavits were sworn out before justices of the peace, circuit court clerks, and notaries public in Iowa and Illinois.

On November 28, 1839, the Prophet and Elias Higbee arrived in Washington D. C., carrying with them a long petition to Congress that recounted in great detail the Missouri abuses and concluded with a plea for federal financial redress, based on the constitutional guarantees of life, liberty, property and religious freedom. The next day they obtained an interview with President Martin Van Buren and presented him with letters of introduction. As soon as he finished reading one of them the President looked at the two men with “half a frown,” saying “What can I do? I can do nothing for you! If I do anything, I shall come in contact with the whole state of Missouri!”4 Joseph and his companion were disappointed but they stood firm and demanded a further hearing. Before they left the President expressed his sympathy for the Saints and promised to reconsider his position.

Joseph then began to circulate the halls of Congress, button-holing senators and members of the House of Representatives in an effort to gain their support. One of these was Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, with whom he would have some very pointed correspondence later concerning the volatile states’ rights issue. He finally met with President Van Buren again but this time, he later wrote, Van Buren treated him “very insolently,” listened to his arguments only reluctantly, and finally said “Gentlemen, your cause is just, but I can do nothing for you. . . . If I take up for you I shall lose the vote of Missouri.” 5

This was a time when the issue of states’ rights was particularly sensitive. The antislavery crusade caused southern states to be especially jealous of their sovereign status and their right to control their own domestic affairs, without interference from the federal government. (Not until after the Civil War and the Fourteenth Amendment was the Constitution generally interpreted the way Joseph Smith understood it.) President Van Buren’s concern that he would lose the state of Missouri and probably other states as well reflected the general sensitivity of politicians for preserving the principle of states’ rights and local control—an issue generally supported by Andrew Jackson’s Democratic party. The issue seemed to hurt the Saints in particular because when they asked President Andrew Jackson earlier to send federal troops to protect them in Missouri, he declined on the grounds that the Constitution forbade such federal intervention without a request from the Governor. That would not be forthcoming from Missouri. It appears that even the idea of providing federal financial aid to the beleaguered Saints had hidden states’ rights as well as other serious political implications.

However, Joseph Smith was highly offended. Van Buren’s whole course, he wrote later, “went to show that he was an office-seeker, that self-aggrandizement was his ruling passion, and that justice and righteousness were no part of his composition. I found him such a man as I could not conscientiously support at the head of our noble Republic.”6

In the presidential election of 1840 Joseph Smith clearly supported Van Buren’s opponent, William Henry Harrison, the Whig candidate. Undoubtedly a majority of the Saints followed his example. Van Buren lost the election, partly because he was blamed for the financial panic of 1837 and partly because of the overwhelming popularity of Harrison, who had become famous as an Indian fighter in the battle of Tippecanoe some twenty years earlier.

From then until his death the Prophet engaged in considerable political activity. In his mind, political action was necessitated by the circumstances, and any action he took was in the full belief that it would best protect the interests of the kingdom of God and its people. At the same time, it is significant that Joseph Smith did not make his political opinions a matter of religious faith or equate them with revelation, even though he obviously hoped and expected that the Saints generally would follow his lead. In 1843, for example, he told a group working on the Nauvoo Temple that “’Tis right, politically, for a man who has influence to use it, as well as for a man who has no influence to use his. From henceforth I will maintain all the influence I can get. In relation to politics, I will speak as a man; but in relation to religion I will speak in authority.”7

Later, in connection with a local election of that year, he declared: “The Lord has not given me a revelation concerning politics. I have not asked Him for one.”8

President William Henry Harrison died after only a month in office. He was succeeded by John Tyler. Joseph Smith and the Mormons had no direct contact with the new president, though in March 1844 he wrote to Tyler urging him to raise 100,000 men to protect Americans settling in Oregon and other American territories. This may have been connected with Joseph’s expectation that some day the Saints would settle in the West.9 He wrote the President again on June 20, 1844. Fearful that mobsters from Missouri were joining with the enemies of the Church in Illinois in an attempt to exterminate the Mormons, he pleaded with Tyler to send them some protection. Nothing came of the plea.

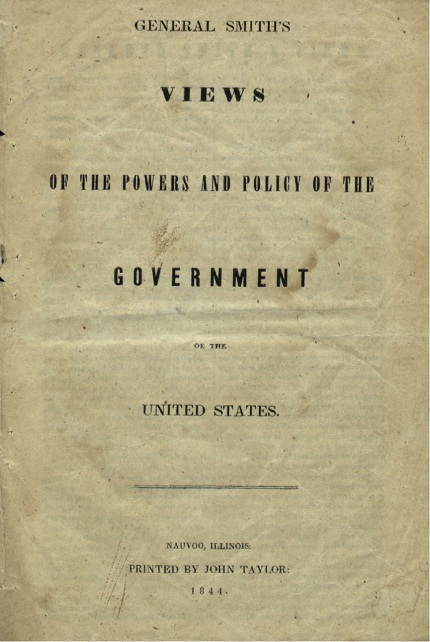

Meanwhile, the Prophet’s experience with national politicians who would not commit themselves to the exercise of federal power in behalf of the Saints was one of the factors that induced him to declare his own candidacy for the office of president in 1844.10 Prior to his decision he wrote several possible contenders, asking what their course of action toward the Saints would be if elected, and none of them sent satisfactory replies. Finally, after consultation with the Quorum of the Twelve and other leaders in Nauvoo, he announced his candidacy and published a pamphlet entitled Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States.11

In this document, which was taken by missionaries to various parts of the United States, Joseph Smith began with an impassioned review of American history, glorifying the administrations of all the previous presidents from George Washington to Andrew Jackson. He characterized Jackson’s administration as the “acme of American glory, liberty and prosperity,” but then, he proclaimed, “our blooming republic began to decline under the withering touch of Martin Van Buren!”

His specific proposals ran the gamut of American concerns. He called for governmental and economic reform, including the creation of a national bank. He demanded prison reform, something many Americans were concerned with but which was not proceeding well.12 He also made clear his opposition to slavery, calling for state legislatures to abolish it and for Congress to pay slave owners for their losses with revenue arising from the sale of public lands.

The most intensely fought issue of the day was expansionism. The Democrats saw America’s destiny as expanding its borders from coast to coast, and called for fully occupying Oregon Territory and incorporating Texas into the Union. The Whigs opposed expansionism, but in the long run this was the issue that got the most popular votes for James K. Polk. Joseph Smith went the Democrats one better. He called not only for the occupation of Oregon and the annexation of Texas but also for inviting Canada and Mexico, if they so desired, to join the Union.13

All this was clearly an effort to demonstrate that he was truly aware of national problems and would not use the office of president merely to promote the interest of the Saints. I believe, however, that to Joseph Smith the most important plank in his political platform was his position on the question of states’ rights, even though it was almost hidden in a very short paragraph. It reflected the Saints’ tragic experience in Missouri by calling for a constitutional amendment that would give the President of the United Sates “full power to send an army to suppress mobs, and the States authority to repeal and impugn that relic of folly which makes it necessary for the governor of a state to make the demand of the President for troops, in case of invasion or rebellion.”

It might be noted that on this issue Joseph was ahead of his time. So far as states’ rights was concerned, the Fourteenth Amendment, adopted 24 years after his run for the Presidency, seemed to fulfill what he called for in his platform. The Fifth Amendment kept the national government from depriving anyone of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. The Fourteenth applied the same restriction to the states, opening the way for the use of federal power to intervene within the states in order to protect those rights.

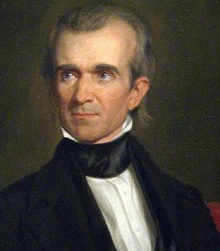

Unfortunately, the Prophet did not live to see the outcome of the election of 1844, for he was brutally martyred in June. In the end, the presidency was narrowly won by James K. Polk, the Democratic candidate, who ran on a platform calling for American expansion.

Polk was a one-term president and, in general, had the support of the Latter-day Saints. In 1846 they had at least one reason to be grateful to him, even though some of them did not recognize it at the time. The Saints were on their way west, and many were camped at Winter Quarters (in what is now Nebraska). Jesse Little had been sent by Brigham Young to request aid from the government, in the form of contracts to build forts and blockhouses along the Oregon Trail. Instead, Polk asked the Saints to raise a force of 500 men to join the army and help out in the War with Mexico. Brigham Young was delighted for this would provide the soldiers money as well as arms and supplies, including the means to move their families west. Thus was created the Mormon Battalion.

By the election of 1848 the main body of the Church was located in what is now Utah, and from then until 1896 the Saints in Utah were unable to participate directly in a presidential election, since only states may appoint presidential electors. During that half-century, however, the Latter-day Saints were vitally interested in national politics, for they affected Utah’s quest for statehood. In some cases a general Mormon attitude toward certain elections might be ascertained; that attitude, however, was purely pragmatic and had nothing to do with religious doctrines. As far as national politics were concerned sides were never taken and presented or interpreted by the Church in such a way as to demand compliance on the basis of religious faith.

The Saints were not particularly fond of Zachary Taylor, the one-term president elected in 1848. Neither was Taylor fond of the Mormons, though he made one interesting proposal that, if it succeeded, would be exactly what the Mormon wanted. The War with Mexico had resulted in the United States acquiring all the territory that now consists of California, Nevada, Utah, most of Arizona, and parts of New Mexico, Colorado and Wyoming. Fearing that Texas, recently admitted to the Union as a slave state, might be carved into several slave states, Polk proposed admitting a large “free state” that would include California and the area the Mormons were calling Deseret. Then, beginning in 1851, that state would be divided into two, California and Deseret. This delighted Brigham Young but the plan failed and Deseret became the Territory of Utah in 1850. It would take Utah nearly a half-century to become a state.

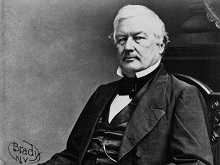

The Saints had a more positive relationship with Millard Fillmore, who served as President 1850-1853. It was he who signed the bill creating the Territory of Utah and then appointed Brigham Young as governor. The Saints’ gratitude for his friendship and consideration was shown when they named the capital city of the new territory Fillmore and the county in which it was located Millard. However, the seat of government was moved from Fillmore to Salt Lake City in 1856.

Fillmore was succeeded in 1853 by Franklin Pierce, who, at first, caused some concern for the Saints because of his reluctance to re-appoint Brigham Young as governor of Utah Territory. In 1854 Colonel Edward J. Steptoe was leading a military expedition to California when he was suddenly diverted to Utah to investigate the Gunnison Massacre. At that time Pierce secretly appointed him as governor of Utah. However, after observing how important it was to the Mormons to retain Brigham Young as their governor and how difficult it would be for anyone else to govern, Steptoe refused the appointment.

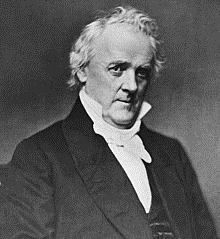

The Saints had cause for special concern in the election of 1856 when the tragically complicated slavery issue was beginning to split the country along sectional lines. The Democrats nominated James Buchanan, who was considered a relatively “safe” candidate because his opinions on the issues were generally unknown. The newly formed Republican party nominated the popular John C. Fremont. They were basically concerned with stopping the expansion of slavery, which, to southerners, seemed to threaten not only slavery but their cherished right of state sovereignty. At the same time the Republican platform took a swing at the Saints in Utah by calling for the prohibition in the territories of “those twin relics of barbarism—Polygamy, and Slavery.” Since the Mormons were now preaching and practicing plural marriage, this seemed like a direct threat to them. If they could have voted, the Mormons would have voted for Buchanan.

Buchanan won by a narrow plurality but, ironically, the Saints did not profit from his victory. In May, 1857, just two months after his inauguration, Buchanan sent a military expedition to Utah to put down a supposed rebellion there. He did this with poor information, for there was no such rebellion, and his mistake has become known in history as “Buchanan’s Blunder.” However, the military remained in Utah until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. Buchanan also antagonized the Saints by appointing a new governor for the Territory of Utah, Alfred Cumming. Thankfully, Cumming and the Mormons got along fairly well, something that did not happen with a few succeeding governors.

In general, throughout the balance of the nineteenth century, the Latter-day Saints seemed to lean toward the Democratic party in national affairs, even though there was no effective organization of either national party in the Territory of Utah. In national affairs, the Republican party seemed to represent a greater threat, for it remained in power through most of the period and was seemingly responsible for most of the legislation aimed at suppressing plural marriage. Actually, however, the Saints could take little comfort in the ascendancy of either party, for the general attitude of reform in the nation made it difficult for any president to favor them.

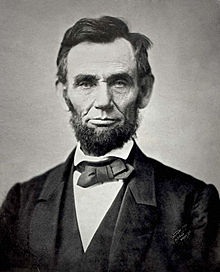

Abraham Lincoln, a Republican, who won the election of 1860, was respected by the Mormons, even though his party was committed to getting rid of plural marriage. He tried to be fair to the Mormons and his general policy was “let them alone.” In 1862, during the early stages of the Civil War, he authorized Brigham Young to raise a temporary military force to protect the telegraph and overland mail. Later that year he signed the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Bill, which outlawed plural marriage in the territories. However, he did not enforce it against the Mormons. One story, which may by apocryphal, suggests that after signing the act he compared the Church to a log he encountered as a farmer. The log was "too hard to split, too wet to burn and too heavy to move, so we plow around it. That's what I intend to do with the Mormons. You go back and tell Brigham Young that if he will let me alone, I will let him alone."14 Whether true or not, the story represents Lincoln’s actual attitude toward the so-called “Mormon Problem.” The following year Lincoln responded favorably to the Mormon request for the release of the bitterly anti-Mormon territorial governor, Stephen S. Harding. The Saints grieved at his assassination in 1865.

The Saints had practically no interaction with Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, but they did not get along well at all with his two-term successor, Ulysses S. Grant. In 1871, for example, Grant appointed James B. McKean as chief justice of the Territory of Utah, with explicit instructions to take the lead in fulfilling the Republican pledge of ending plural marriage. He kept up his pressure to forbid the practice. Nevertheless, in 1875 he became the first U.S. President to visit Utah. Though he did not change his mind on plural marriage, he was highly impressed with the Mormon people and Brigham Young was delighted with his graciousness and the fact that he did not show any favoritism toward the anti-Mormon groups in the territory.

Republican Rutherford B. Hayes (elected in 1876 only after the Supreme Court made a momentous decision on certain contested state election returns) kept up the anti-polygamy pressure. In 1879 he went so far as to ask the nations of Europe to prohibit Mormon emigration to Utah. The following year he appointed another anti-Mormon governor, Eli H. Murray. His successor, James A. Garfield, seemed a bit more friendly to the Mormons, and his assassination after less than a year in office truly saddened them. To show their respect, a month after he died they named a Utah county after him. Chester A. Arthur, Garfield’s Vice President, succeeded him and began his administration by vigorously urging stepped-up prosecution of plural marriage. In 1882 he signed the Edmunds Bill, which strengthened the power of the government to prosecute those involved in the practice.

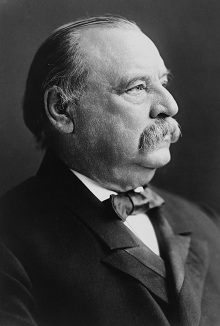

In 1884, even though people living in the territories could not vote in national elections, the Church came as close to endorsing a presidential candidate as at any time since 1844. The Church-owned Deseret News praised the Democrats’ nomination of Grover Cleveland, and the Saints were generally delighted when he was elected by a narrow margin over Republican James G. Blaine. The News stated, in an editorial on November 14, 1884:

The “Mormon” people lean to Democratic principles because those principles are in consonance with the Constitution and preservative of local and individual rights. They do not anticipate any fraternization of the Democratic party with “Mormon” institutions, secular or religious. They do not put their trust in parties in any way. They look for decided opposition from the party now rising from the obscurity of twenty-four years. … But they think that, for a season, at least, that party will not be likely to ignore those constitutional restrictions which are the safeguard of popular government. … They think that a change of Federal officials for the Territory must in the main be some improvement.

But Cleveland did little to comfort or aid the Saints either by suggesting leniency for them or changing the federal officials in Utah, as the Saints had hoped. Instead, he devoted a long section of his first annual message to conditions in Utah, urging the continued prosecution of the Church and a restriction upon Mormon immigration from other countries.

There was, nevertheless, a general feeling—right or wrong—that the Democratic party was more sympathetic toward the Saints and more likely to grant statehood to Utah, so it was with apprehension that they greeted the return to power of the Republicans when Benjamin Harrison defeated Grover Cleveland in 1888. This was especially true since the Republican party’s platform once again contained an anti-Mormon plank. Sure enough, he quickly appointed another anti-Mormon governor. Like his predecessors, he also continued to support anti-Mormon legislation.

However, in 1890 President Wilford Woodruff issued the Manifesto, which brought plural marriage to an official end.15 At first President Harrison was suspicious of President Woodruff’s sincerity, but after visiting Utah in 1891 he mellowed. In 1892 Grover Cleveland was elected for second time and in 1894 he granted pardons to Latter-day Saints who were previously disfranchised by the anti-polygamy laws. Bringing a long and often bitter tension between the Mormons and the national government to an end, it was Cleveland who signed the bill admitting Utah into the Union on January 4, 1896.

Because their territory was now a state, the year 1896 was the first year in which the citizens of Utah could participate fully in a presidential election. By that time the Saints had no apparent reason to lean toward either political party or candidate on the basis of its attitude toward the Church, for both parties had joined in supporting statehood for Utah after the Manifesto. In the background, however, it appears that most Mormons were still dismayed with the Republican Party, which had been so vigorous in its opposition to the institution of plural marriage, and they seemed to blame the Republicans for postponing statehood too long.

As it prepared for Utah statehood prior to 1896, the Church set about to destroy the appearance of political partisanship. The “People’s Party,” which had actually been the Church party with regard to territorial politics, was disbanded and Church leaders vigorously encouraged members of the Church to join either of the national parties. The relationship between the Church and the nation changed in the twentieth century, as did the relationship between the Mormons and the U.S. Presidents. That story will be told in Part II.

ENDNOTES

1. Most of this article is drawn (sometimes verbatim) from an article I published a little over thirty years ago. See James B. Allen, “The American Presidency and the Mormons,” Ensign (October 1972), 36-56. Much of the rest is based on Michael K. Winder, Presidents and Prophets; The Story of America’s President and the LDS Church (American Fork, Utah: Covenant Communications, 2007).

2. Electors have voted contrary to their pledges over 150 times. Seventy-one votes were changed because the original candidate died before the elector could cast a vote. In two instances electors chose not to vote for anyone. Others changed their votes as a result of personal interest or, perhaps, simply by accident. On only one occasion have so-called “faithless electors” come close to changing an election result. This happened in December 1836 when twenty-three electors prevented Richard Mentor Johnson from winning the Vice Presidency. However, the next February, since no one had a majority electoral vote, the U.S. Senate elected him as Vice President, as provided by the Twelfth Amendment. (See “Faithless Elector” in Wikipedia.)

3. It might be noted that as of that date only white, property-holding males could vote.

4.Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Period I, ed. B. H. Roberts (Salt Lake City: Published by the Church, 1949), 4:40.

5.Ibid, 4:80.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid. 5: 286.

8. Ibid.,526.

9. See Ibid. 5:35 where it is recorded that on August 6, 1842, Joseph Smith said “the Saints would continue to suffer much affliction and would be driven to the Rocky Mountains,” and there become a “mighty people.”

10. Several sources deal with Joseph Smith’s candidacy for President. A rather exhaustive list may be found by going to mormonhistory.byu.edu, and doing a subject search for “Smith, Joseph, jr., political activities.” Among the articles listed there are: James B. Allen, "Was Joseph Smith a Serious Candidate for the Presidency of the United States ...?" Ensign 3 (September 1973): 21-22; Arnold Garr, “Joseph Smith: Candidate for President of the United States,” Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: Illinois, ed H. Dean Garrett (Provo, UT: Department of Church History and Doctrine, BYU, 1995), 151-68; Arnold Garr, “Joseph Smith for President: The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in New England, Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: The New England States, ed. Donald Q. Cannon et. al. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004): 47-63; Martin B. Hickman, The Political Legacy of Joseph Smith, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 3 (Autumn 1968): 22-27; Richard D. Poll, “Joseph Smith’s Presidential Platform,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 3 (Autumn 1968): 17-21; Margaret C. Robertson, “The Campaign and the Kingdom: The Activities of the Electioneers in Joseph Smith’s Presidential Campaign,” BYU Studies 39, no. 3 (2000): 147-80.

11. See Smith, History, 6:197–209. The pamphlet was actually written largely by a close friend and scribe, W. W. Phelps.

12. His proposal for prison reform was unusually radical for the time: let all the prisoners go, except murderers, telling them to “go thy way and sin more,” then have the states punish felons by making them work on roads, public works, or any other place where they could learn wisdom and virtue and become more enlightened. In addition, penitentiaries should be turned into “seminaries of learning, where intelligence, like the angels of heaven, would banish such fragments of barbarism.” Such proposals may seem strange today but they at least reflect the Prophet’s sensitivity to the social problems of his day. Most prisons were filthy, unhealthy, poorly managed, and did little if anything to facilitate personal reform. Joseph knew, because he had spent time in some.

13. Interestingly enough, it was during Polk’s administration that the present northern boundary of the western United States, the 49th parallel, was defined by treaty with England, that Texas was annexed, and that the War with Mexico began, ending up in the acquisition of most of the western United States, including California and Utah.

14. This story is reported in Gustave O. Larson, The Americanization of Utah for Statehood (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1971), 60-61, and repeated in Edward Brown Firmage and Richard Collin Mangrum, Zion in the Courts: A Legal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830-1900 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 139. Various other sources attribute such a “plow around it” statement to other situations. In any case, whether apocryphal or not, the story represented Lincoln’s very pragmatic attitude toward the “Mormon problem.”

15. I say “official” end because, in practice, plural marriage did not stop all of a sudden. Some marriages continued to be performed in secret, though not authorized by Church leadership, and others were performed in Mexico, where presumably they were not illegal. A so-called “Second Manifesto” in 1907 ended all that, except for some offshoot groups that were excommunicated from the Church.

| Copyright © 2024 by James B. Allen | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |