| Print | Back |  |

January 14, 2013 |

|

Moments in Art JB Fairbanks, Pioneer Artistby Lawrence Jeppson |

At the start of 1930, imaginative folks were two years deep into the planning of the “A Century of Progress Exposition,” the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933. The fair was so successful it ran for an additional year and welcomed 48 million visitors.

The location was 425 acres on the shore of Lake Michigan within walking distance of the city’s downtown. The fair celebrated color and lighting: it was opened when its lights were turned on with magnified energy from the rays of the star Arcturus. A highlight was a heralded visit from the Graf Zeppelin.

Celebrating the city’s centennial, the exposition focused on industrial achievement and scientific and technological progress rather than architectural bravado.

The fair featured two long lagoons parallel to the lake. A modernistic Hall of Religion was built facing east on the marge of one of the lagoons. The pavilion was an incredible 400 feet long. Its contents were ecumenical: a dramatic mixture of various Christian and non-Christian participants. There was a strong showing of religious art: paintings, sculptures, carvings, porcelains, etc.

The official exposition catalog stated, page 55: “Historic sculpture commemorative of the Mormon hegira to Utah is shown by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. There is also a model of the Temple in Salt Lake City.”

What the catalog failed to state was that the Mormon presentation also included paintings dramatizing Mormon accomplishment in Utah. J.B. Fairbanks’ painting The Desert Shall Blossom (also known as The Beginning of Irrigation in Western Civilization) was created especially for this event.

J.B. Fairbanks was born in Payson, Utah in 1855, just eight years after the first Mormon pioneers arrived in Utah. Because he had the same name as his father, John Bolyston Fairbanks, he is referred to by his initials. The father had artistic abilities; the son excelled and began what became, at last count, four generations of gifted artists.

Although J. B. had nascent skills, it was not until he was 18 that he decided he wanted to be an artist. He was influenced by his close childhood friend John Hafen (1856-1910), who became his first teacher. Although Swiss-born Hafen was half a year younger, for five years he had been studying in Salt Lake City under the Norwegian emigrant artist Dan Weggeland (1827-1918), considered the father of Utah art, and George M. Ottinger (1833-1917), another pioneer artist.

In 1890 the infrastructure of the Salt Lake City Temple was nearing completion and Church leaders were concerned about depictions on the interior rooms. John Hafen and Lorus Pratt (1855-1923) proposed that the Church finance their studies in Paris and, in return, they would paint the scenes in the temple’s ordinance rooms. Three smaller previous temples in other Utah communities had been decorated by pioneer artists. Hafen wanted something better. Hafen later requested that J.B. be included. The Church’s First Presidency decided to accept the proposal and added J.B. Fairbanks to the group, who would be called and set apart as art missionaries to study in Paris.

In the summer of 1890 the three set out for Paris. Later Edwin Evans (1860-1946) and Herman Hugo Haag (1871-1895) would serve similar missions, and all would be back in Salt Lake to work on the Temple art. Fairbanks wrote that he started the departure day by getting up at 4:00 a.m. to work on a portrait. The date was the day before J.B., who was 34, and his wife would celebrate their 13th wedding anniversary. He and Lillie already had eight children, aged from one to 12. (The oldest was Leo, who became a very good painter, and the youngest was Avard, who became an internationally known sculptor.)

In Paris Fairbanks, Hafen, and Pratt enrolled in the Académie Julian, the most popular art school in France, so internationally popular and crowded that it taught from nine studios scattered about the city, five for men, four for women. The Utahns studied figure painting in the studio and landscape painting outside.

Competition was fierce and the teachers demanding, but the Utahns worked hard, did well, and received some recognition. Fairbanks’ activities are recorded in his journals and many letters home to his wife.

Fairbanks “hoped that if he utilized his time, he could develop sufficient skills within one year . . . he developed an intense schedule. He would arise at 5:30 a.m., and, after getting ready for the day, devote thirty minutes to the study of anatomy or French. Upon arriving at the Julian, he would sketch for several hours. During the lunch break he continued his study of anatomy, followed by another four hours of sketching. He would then go home to accomplish some chores before attending night classes for three hours.” (Rachel Cope, “With God’s Assistance I Will Someday Be an Artist,” BYU Studies, Number 3, 2011, p.141)

One of J.B.’s teachers, Benjamin Constant (1845-1902), a distinguished portrait painter, was so pleased with J.B.’s progress that he encouraged him to go deeper with his landscape training. In the summer of 1891 J.B. spent some time in the small village of Chilleurs “under the tutelage of Albert Schultz.” He “spent his second summer working under the personal direction of landscape artist Albert Gabriel Rigolot (1862-1932). . . Rigolot enjoyed portraying riverscapes and landscapes and was admired for his naturalism. (ibid, p.143)

Prior to their training in Paris, the work of these frontier artists was “considered unsophisticated, with inaccuracies in perspective and proportions and showing limited technique.” [Giles H. Florence, Jr, “Harvesting the Light,” Ensign magazine, Oct., 1968] Afterwards, they painted with greater proficiency. They also perfected their abilities to paint in plein aire, outside the studio, and, profiting from the disciplines and discoveries of Impressionism, to discern the many effects of light on their subjects.

Hafen had to return after a year, but Fairbanks and Pratt stayed on until the next year. By the beginning of 1893 the Paris Art Missionaries were painting the murals in the Temple’s world and garden rooms.

After that J.B. went to Mesa, AZ to work on the murals for the new LDS Temple there. In Utah he painted portraits of church and business leaders and a variety of Utah landscapes. More than any of the other Utah artists who trained in France, his Impressionism inclined towards Tonalism, an aesthetic which was stronger in America than in Europe.

It was never easy for a frontier artist with eight children to make a living from his art. (After his wife died, J.B. eventually remarried at the age of 60 and fathered five more children.) J.B. worked at various jobs, not all of them artistic, and took up photography.

In 1900, before his second marriage, he was hired by the Cluff Archaeological Expedition to draw, paint, and photograph its explorations in South America. Cluff was searching for Book of Mormon sites. The expedition lasted two years, during which J.B. made many sketches which he later turned into “beautiful paintings.” (Springville Museum of Art/Collections.)

J.B. settled in Provo for a period, teaching at Brigham Young Academy and opening a photographic studio. He moved to Ogden to become the first supervisor of arts in the city’s schools. He later moved to New York City so that his son Avard could study art. He and his wife settled in the East.

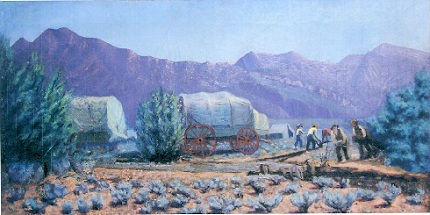

J.B. was 74 when he painted The Desert Shall Blossom. Within days after the Mormon pioneers entered the Salt Lake Valley in late July, 1847, they dug irrigation ditches and built a low diversionary barrier across City Creek on the northeastern end of the valley to divert water towards land which would be cultivated. At first the earth was so hard that it had to be soaked before it could be plowed. This important, very large picture (24 x 48") depicts the start of this process.

The bulk of the picture is a landscape: the high, ragged hills in the background; the clear blue desert sky of deep summer; the sage foliage and large juniper trees in the bottom half; and two parked covered wagons. For all this panoramic beauty, the eye quickly discerns that the soul of the picture is the small group of four men on the right who are working to make the desert bloom. The second man from the left is guiding a plow being pulled through the earth as it is being softened from the diverted waters. The two men on the right appear to be building the diversionary weir. A tent and the unhitched wagons show that the work party will be here for some time.

The picture is also a tribute to hard work, long-time vision, and formidable dedication. One is reminded of the French Barbizon painter Jean François Millet (1814-1875), who broke from tradition to glorify the hard work of peasant farmers. Millet, however, never had such a powerful backdrop for his depictions.

The Desert Shall Blossom is more than a commemorative tribute. It is a beautiful painting.

The Desert Shall Blossom has recently been given by Dr. David Fairbanks, the physician son of Avard and grandson of J.B. Fairbanks, to augment the ten or so paintings by the artist already belonging to the splendid Springville Museum of Art. (The museum itself is the outgrowth of a few paintings by Fairbanks and other pioneer painters given to the town’s high school.) Most of these paintings are from the painter’s earlier years. The Desert Shall Blossom is an important climax to the cycle.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |