| Print | Back |  |

January 2, 2013 |

|

Rambling Thoughts on Church History Some Merry and Not-so-Merry Christmases and Some Happy and Not-so-Happy New Years: Holidays with the Prophet Josephby James B. Allen |

Most of us who read these columns have just enjoyed a joyous holiday season. The terms “Merry Christmas” and “Happy New Year” were probably realistic wishes. Even though we may not have had all the physical and financial comforts we would like, we were, for the most part, warm and comfortable on those days, and grateful for our many blessings.

As I prepared for Christmas, I thought again about the Prophet Joseph Smith and wondered anew how he and his family spent their Christmas and New Year seasons. Accordingly, I browsed Joseph Smith’s History (compiled by committee under the direction of Joseph Smith)1, as well as the recent publications of Joseph Smith’s personal journals,2 and pulled out what I could.3

As we look at Joseph Smith’s Christmases we should not expect that they should parallel our own. Christmas in America in those days was not what it is today. In fact, the earliest settlers of Massachusetts considered it to be an impure pagan holiday, and celebrating it was even outlawed in Boston from 1659-1681. Others, however, particularly those in the southern colonies, observed it as a special day, though not with the kind of festive celebrations and elaborate commercialism that we have grown up with. It was only during Joseph Smith’s lifetime that Christmas gradually became a day of special celebration and religious observation.

Even though a character something like Santa Claus, or St. Nicholas, existed in European tradition, the Santa Claus tradition had its American origins only in the early nineteenth century. The patron saint of the New York Historical Society was a jolly elf named St. Nicholas. Washington Irving joined that society in 1809 and soon published a satirical history of New York that made many references to St. Nicholas. The elf became more popular, and more clearly tied to Christmas, after the poem we now know as “The Night Before Christmas” appeared in 1823, under the title “A Visit From St. Nicholas.” The authorship is controversial but it is most commonly believed that it was written in 1822 by Clement Clarke Moore, while he was Christmas shopping. Others say the author was Henry Livingston, Jr. Interestingly enough, both later claimed credit for it. It was not until 1863 that St. Nicholas became Santa Claus in the American mind.

In 1819, the year before Joseph Smith was born, Washington Irving made another contribution to Christmas when he wrote a series of essays, published serially under the title “The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon.” Some of these stories were about Christmas and depicted the warm-hearted English customs that Irving grew up with. Most scholars believe that this sketch book affected the way Americans observed Christmas. According to Charles Dickens, it also had an influence on his Christmas stories, including A Christmas Carol, first published in 1843. Partly as a result of Irving’s stories, traditions of caroling, gift-giving, etc. began to be more popular in America.

But the customs caught on only gradually. In Nauvoo, for example, children even attended school on December 25, for Christmas was not a legal holiday. Gradually some states made it a state holiday, but it did not become a national holiday until 1870. Christmas trees, cards, and even gift-giving were uncommon. Rather, spending the evening with family, enjoying a meal, and sometimes music and dancing were the order of the day.

With this background, we should not be surprised to find that the Prophet Joseph Smith made little mention of Christmas, or New Year, in his own records. It is possible, however, to ascertain some things he did during those times, all of which reflect some aspects of Church history.

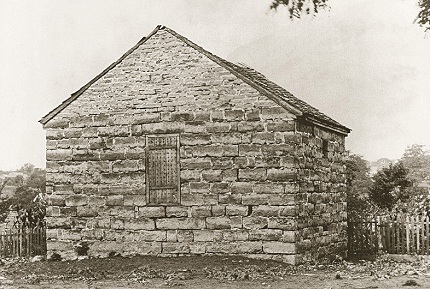

SharonVt.jpg)

In a sense, Joseph Smith himself was his family’s Christmas present in 1805. He was born that year on December 23, just two days before Christmas, though it is not clear that the Smith family, living in New England, even recognized December 25 as a special day. At that time Joseph Smith Sr., Lucy, and their three older children (seven-year-old Alvin, five-year-old Hyrum, and two-year-old Sophronia) lived on the family farm in Sharon, Windsor County, Vermont.

Exactly what Joseph was doing during the Christmas season in much of his early life is unknown. However, a few things may be surmised. During his first few years his family did whatever celebrating they did as most farming families in that area—not much, if anything, in the way of celebration and presents, but perhaps some expressions of devotion to the Savior. It is clear that they were a religious family. In 1811 they moved to West Lebanon, New Hampshire where, in 1813, Joseph had his famous, terribly painful, leg operation. This and the complicated aftermath left him so terribly weak and thin that his mother sometimes had to carry him. For the next three Christmas seasons he was on crutches.

By Christmastime in the year 1816 the Smith family had moved to the vicinity of Palmyra, New York, where they lived for a time in a small rented home. By Christmastime the next year they were in their two-room log cabin, where they still lived at the time of Joseph Smith’s First Vision and, later, the visit of Moroni. By Christmastime 1825 they were in their new frame home that had been completed in the fall of that year. Just what they did to celebrate Christmas during these years is unknown.

We have an idea of what Joseph might have been thinking about on Christmas and New Year’s Day, 1825-26. He was in love with Emma Hale, of Harmony, Pennsylvania, but her father did not approve of their getting married. No doubt this weighed heavily on both their minds during that season, so much so that they finally decided to elope. They were married at South Bainbridge, New York, on January 18, 1826. They were living with Joseph’s parents the next Christmas (the same year Joseph received the plates of the Book of Mormon), but the following Christmas season they were living in Harmony with Emma’s parents (her father now reconciled to Joseph). A year later they had their own small home, on property obtained from Emma’s father.

In 1830 the Church was organized, and from then on, because of records kept by Joseph and others, we have a better idea of what he was doing during the Christmas/New Year season. (We call it the “Holiday Season” today, but I doubt that anyone used this term at that time.) In August, Joseph and Emma left Harmony and accepted an invitation to stay in the home of Peter Whitmer, Jr., in Fayette, New York. We don’t know what they did on Christmas day, but there, in December, Joseph received three important revelations. They now constitute sections 25, 26, and 27 of the Doctrine and Covenants. Especially significant (at least in my mind) was Section 25. This was a revelation to Sidney Rigdon, who had been a prominent minister in the area of Kirtland, Ohio, and had been converted to the Church by reading the Book of Mormon. He had come to New York to became acquainted with the Prophet. He soon became one of Joseph’s closest associates and counselors. That Christmas season, Joseph had this and much more to be thankful for.

One of the revelations mentioned above directed the Prophet to move the main body of the Church to Kirtland, which was done early in 1831. At the end of that year Joseph was doing missionary work during the Christmas season. Early in December he received two revelations (now sections 71 and 72 of the Doctrine and Covenants), the first of which commanded him and Sidney Rigdon to “proclaim unto the world in the regions round about, and in the church also, for the space of a season (D&C 71:2).” As recorded in his History, “From this time until the 8th or 10th of January 1832, myself and Elder Rigdon continued to preach in Shakersville, Ravena, and other places, setting forth the truth. Vindicating the cause of our Redeemer.” Clearly, whether or not they did anything special on Christmas, Joseph and Sidney were thinking about the Savior and His mission.

As Christmas approached in 1832 Joseph Smith had his mind on some of America’s especially tense political problems. On Christmas Day his concern resulted in a revelation. The United States was close to civil war after the state of South Carolina threatened to nullify an act of Congress within its borders. President Andrew Jackson was irate, considering such an act a rebellion. He assembled troops and threatened to march into South Carolina if the state did not follow the law of the land. South Carolina finally backed down, but at the same time proclaimed its right as a sovereign state to go against federal law if it so wished. Joseph Smith, too, considered South Carolina’s action a rebellion. I suspect that he wondered what might happen as these tensions were exacerbated, and that on Christmas Day he may have been both pondering and praying about it. At any rate, on that day he received one of his most well-know revelations, the Prophecy on War (section 87 of the Doctrine and Covenants), foreshadowing the Civil War that broke out nearly thirty years later. Two days later he received one of his most-quoted revelations, the all-important Section 88, often referred to as “The Olive Leaf.”

There is no specific account of what Joseph did on December 25, 1833 or January 1, 1834, but we know from his History something of what he must have been thinking about. The history shows him concerned about and working on the internal affairs of the Church as well as the persecutions that continued to plague his followers. It could not have been an extremely happy time. Joseph’s own record is equally blank for the 1834-35 season, except a notation that during the month of January he was engaged in the school of the Elders and also preparing the “Lectures on Faith” that were published in early editions of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Christmas Day 1835 is the second time we have a specific entry in Joseph’s history as to exactly what he was doing that day. (The first was 1832.) On the day before Christmas he was at home in the morning but spent the afternoon surveying a road. On Christmas Day, however, his history has a joyous entry: “Enjoyed myself at home with my family, all day, it being Christmas, the only time I have had this privilege so satisfactorily for a long period. Brother Jonathan Crosby called this evening.”

That was the occasion described by Jonathan Crosby himself, who gave a few more details on what was happening on Christmas Eve as well as Christmas Day. Crosby, a recent convert, came to Kirtland to meet the Prophet and went to his home on Christmas Eve. There he found Joseph with a group of friends and family, including Hyrum Smith, Reynolds Cahoon, Martin Harris, John Carl, and George A. Smith. Joseph invited Crosby in and he joined them in a “very pleasant time” where they drank “peper [pepper] and cider”4 and had supper. Apparently Joseph also put him up for the night. On Christmas Day Crosby was invited to a “feast” where Joseph Smith Sr., the Church Patriarch, gave blessings.5

New Year’s Day 1836 was a day of both thanksgiving and renewal for Joseph Smith. His thanksgiving is seen in the first part of his journal entry for that day:

This being the beginning of a new year, my heart is filled with gratitude to God that he has preserved my life and the lives of my family. while another year has passed away. We have been sustained and upheld in the midst of a wicked and preverse [perverse] generation, although exposed to all the afflictions, temptations, and misery that are incident to human life; for this I feel to humble myself in dust and ashes, as it were, before the Lord.6

At the same time, Joseph was deeply troubled by difficulties between himself and his brother William, but New Year’s Day became a day of reconciliation and renewal. His father, his brothers William and Hyrum, his uncle John Smith, and Martin Harris all met at Joseph’s home. Much of the difficulty had arisen because of William’s criticism of the Prophet. Joseph Sr. prayed fervently, “with all the sympathy of a father, whose feelings were deeply wounded on account of the difficulty that was existing in the family.” But soon “the Spirit of God rested down upon us in mighty power.” Their hearts melted, William humbly asked Joseph’s forgiveness, Joseph asked William’s forgiveness and, said Joseph, “the spirit of confession and forgiveness was mutual among us all.” They made solemn covenants to build each other up, not listen to evil reports, and, like brothers, go to each other with their grievances and be reconciled. After that the brothers called in Joseph’s wife, Emma, their mother, and his scribe and repeated their covenants before them. Tears flowed and Joseph closed the meeting with prayer. “It was truly a jubilee and time of rejoicing,” he said.

Christmas Day 1835 was the last account in Joseph’s History, until 1843, of any holiday season celebration. I cannot imagine that he ignored Christmas but, so far as the records are concerned, during all those years he was preoccupied with Church business and various family concerns. Two days before Christmas 1836, for example, he presided over a conference in Kirtland, and on January 2, 1837 he attended a meeting of the Kirtland Safety Society (a banking institution). All his history notes about the end of the year 1837 is the bitter apostasy and persecution in Kirtland, including Brigham Young being forced to flee simply because “he would proclaim publicly and privately that he knew by the power of the Holy Ghost that I was a Prophet of the Most High God, that I had not transgressed and fallen as the apostates declared.” The history for that year then closes with the unhappy notation that “apostasy, persecution, confusion, and mobocracy strove hard to bear rule at Kirtland, and thus closed the year 1837.” It was a sad Christmas season, indeed. The History included a similar comment about the new year: “January 1838,— A new year dawned upon the Church in Kirtland in all the bitterness of the spirit of apostate mobocracy; which continued to rage and grow hotter and hotter, until Elder Rigdon and myself were obliged to flee from its deadly influences.” The two left Kirtland for Missouri on January 12.

When Christmas came in 1838 Joseph, along with his brother Hyrum and a few others, were wrongly incarcerated in the fourteen by fourteen dungeon of a jail at Liberty, Missouri. Conditions were horrible: only a trap door for entrance, a dirt floor covered with old straw, no stove, intolerable smoke if they lit a fire, not enough blankets for warmth, and nearly unpalatable food. Joseph received a visit from Emma on December 8 and again on December 20 and 21.

Other than Emma’s visits, the Prophet’s Christmas and New Year season was anything but merry or happy. Nevertheless, his prison experience did not rob him of patience, longsuffering, or his assurance of continuing revelation, as expressed in revelations he received there that have since taken their place as sections 121,122, and 123 of the Doctrine and Covenants. Also, it resulted in some remarkable letters near Christmastime. Just nine days before Christmas he wrote a long letter to the Church saying, in part, “Know assuredly, dear brethren, that it is for the testimony of Jesus that we are in bonds and in prison.” No doubt he was thinking of this on December 25. In that same letter he expressed his own continuing faith and strength:

Dear brethren, do not think that our hearts faint, as though some strange thing had happened unto us, for we have seen and been assured of all these things beforehand, and have an assurance of a better hope than that of our persecutors. Therefore God hath broadened our shoulders for the burden. We glory in our tribulation, because we know that God is with us, that He is our friend, and that He will save our souls.

On New Year’s Day, 1839, expressing his disappointment at the failure of the law to protect their liberty, Joseph made the following lament from jail: “The day dawned upon us as prisoners of hope, but not as sons of liberty. O Columbia, Columbia! How thou art fallen!” Though the season was anything but merry or happy, it was a time of hope and optimism for the Prophet.

Joseph and Hyrum remained in captivity until they escaped on April 18. Not long after, he joined the main body of the Church in Illinois and assisted in founding the city of Nauvoo.

During the 1839-40 Christmas/New Year season Joseph Smith was not at home. On November 28 he arrived in Washington D.C., where he visited with President Martin Van Buren and circulated the halls of Congress as part of a delegation trying to obtain federal recompense for the losses the Saints had suffered as a result of the Missouri persecutions. He spent the last part of December, including Christmas, and most of January in Philadelphia doing missionary work and attending to other Church duties. He was back in Washington in February and back in Nauvoo by March 1. During all this time he had much on his mind, but two things stood out. One was the reason he went to Washington. The other was the concern he had for the members of the Quorum of the Twelve who had been called to fulfill an all-important mission to the British Isles that, he believed, would ultimately be the “salvation of the Church.” (See our column that appeared in Nauvoo Times on November 27.)

At the end of 1840 Joseph Smith’s mind was very much on the activities of the Quorum of the Twelve in England, for that is the major content of his History for the last several days. Also that month he found pleasure in the state’s approval of the Nauvoo city charter.

As usual, Christmastime 1841 saw Joseph Smith deeply immersed in Church business. On Christmas eve he spent time talking with Bishop Newel K. Whitney and Brigham Young about establishing an agency to help bring Saints inexpensively from England to Nauvoo. “In the name of the Lord,” he said, “we will prosper if we go forward with this thing.” The entry in his History for Christmas Day shows several apostles and their wives spending the evening having dinner at the home of Hiram Kimball, after which Kimball gave each of the Twelve a gift of a parcel of land. Curiously there is no mention of Joseph being at that gathering, nor any indication of what he did that day. Clearly, however, he was enjoying much more peaceful and satisfying times than in earlier years. On New Year’s Day he began placing goods on the shelves of his new store in Nauvoo. He opened the store for business four days later.

In 1842 Joseph spent the day before Christmas working with Willard Richards on revising his history. A week later, on New Year’s Day, he was in Springfield, Illinois, where he spent several days in connection with an effort by the state of Missouri to extradite him. Eventually the judge ruled in his favor.

On December 25, 1843, Joseph’s History finally includes an extensive entry about festive activities on Christmas Day. It was almost as if, with a great sigh of relief, Joseph and his family could at last celebrate that day the way many other Americans were celebrating by that time—as a day of rejoicing and festivity.

The Saints who began the day must have been especially eager to please the Prophet, for at one o’clock in the morning Letti Rushton (widow of Richard Rushton, who had been converted to the Church in England by George A. Smith), accompanied by her three sons, their wives, and her two daughters with their husbands, along with several neighbors awoke him with their singing of “Mortals, awake! With angels join.” Rather than being disturbed by such an early awakening, Joseph said that he felt “a thrill of pleasure to run through my soul.” Everyone in his household, including several boarders, got up to hear the serenade. “I felt to thank my heavenly father for their visit,” he said in his History, and blessed them in the name of the Lord. Next the serenading troop awakened Joseph’s brother Hyrum, who went outside, shook hands with and blessed each of them, and remarked that at first he thought he was listening to a cohort of angels.

Joseph spent the rest of the day at home, at noon giving counsel to some brethren from the nearby Morley settlement. At 2 o’clock he hosted about fifty couples at what must have been a scrumptious dinner. Later a large group had supper at his house and then spent the evening enjoying music and dancing.

As the evening went on something totally unexpected, and especially heartwarming for the Prophet, happened. As described in his History:

A man with his hair long and falling over his shoulders, and apparently drunk, came in and acted like a Missourian. I requested the captain of the police to put him out of doors. A scuffle ensued, and I had an opportunity to look him full in the face, when, to my great surprise and joy untold, I discovered it was my long-tried, warm, but cruelly persecuted friend, Orrin Porter Rockwell, just arrived from nearly a year’s imprisonment, without conviction, in Missouri.

“I rejoiced that Rockwell had returned from the clutches of Missouri, and that God had delivered him out of their hands,” Joseph recorded the following day.

A week later Joseph’s New Year’s Day was also a day of celebration. Again he hosted a large party at his home, the Mansion House, where there was music and dancing until morning. But Joseph did not spend all the evening in these festivities. Instead, he spent much of it in his private room with his family, Elder John Taylor, and some other close friends.

The delightful and poignant Christmas Day and the enjoyable and intimate New Year’s Day were, indeed, a “Merry Christmas” and a “Happy New Year” for the Prophet. But these were his last such days, for he was murdered just six months later. However, that Christmas/New Year week was indeed a fitting conclusion to a series of such seasons that were sometimes marked with pleasure and hope and other times with sorrow and suffering. The episodic tale told here only suggests how devoted the Prophet really was to his friends, his family, his thousands of followers, and, most importantly, to the Savior and His gospel.

Notes

1. Smith, Joseph, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Ed. B. H. Roberts. 7 vols. Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1950. (Only the first six volumes relate directly to Joseph Smith.)

2. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman, general editors, The Joseph Smith Papers :Journals, Volume I: 1832-1839, Volume 2: December 1841-April 1843 (Salt Lake City: The Church Historian’s Press, 2008, 2011).

3. Several books and articles deal with the Christmases not only of Joseph Smith but also other early Church members, including the Utah pioneers. Among them are Susan Arrington Madsen, Pioneer Christmas: Excerpts from Personal Journal (Sandy, UT: Leatherwood Press, 2007); Laura F. Willes, Christmas with the Prophets (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010); Larry C. Porter, “Remembering Christmas Past: Presidents of the Church Celebrate the Birth of the Son of Man and Remember His Servant Joseph Smith,” BYU Studies 40:3 (2001), 49-119 Caroline H. Benzley, “Christmas with Joseph Smith,” New Era, 31 (December 2001), 8-10; Richard Ian Kimball, “‘All Hail to Christmas’: Mormon Pioneer Holiday Celebration,” BYU Studies 40:3 (2001), 6-26. In preparation I read some of these in addition to Joseph Smith’s History.

4. Apple cider was a common American beverage in the nineteenth century. Usually it was hard apple cider, often spiced up with cayenne pepper.

5. Porter, “Remembering Christmas,” 52.

6. This is as it appears in the published History. In the recently published personal journals the punctuation is slightly different.

| Copyright © 2025 by James B. Allen | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |