| Print | Back |  |

October 29, 2012 |

|

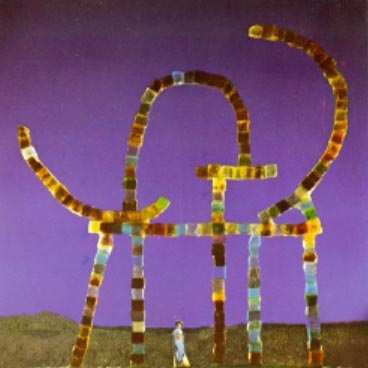

Moments in Art Not a Prophet at Homeby Lawrence Jeppson |

There is another story I must tell about the French abstract painter Jean Piaubert (1900-2002). Some might call it a story of retribution or, less acidic, a comeuppance.

An artist’s career frequently is shaped by accidents and the unexpected. This happened to him on two notable occasions. I recounted the first in last week’s “Moments.”

I met Jean through a referral from some tapestry artists. Because of their urgings he had done a few tapestry cartoons. I called on him at his studio and was shown his latest paintings. We struck up a friendship. Whenever I was in Paris I’d visit with him; that lasted until suddenly he was no longer there.

I could not find him. Later I learned he and his wife had retired to Southern France. He lived to be 102, and I attribute that to his life as a creative artist and to the care of a loving wife. Good genes probably helped.

Jeanne was a woman of artistic sensibility, and she encouraged him. She also had remarkable business instincts. She established a lucrative business manufacturing and selling fashionable beauty products. Sometimes this was detrimental to her husband’s success. Dealers looked down on him because, they growled, he had never had to live in a dirty garret, scrounge for food, or suffer for his art. He was succeeding because of her wealth. The real reason they disparaged him: he was not dependent upon them.

Piaubert became a pioneer in abstract art when one of his paintings was carelessly turned upside down and he saw it in a completely new way. As we saw in the previous “Moments,” that accident shaped his art forever.

A second crucial unanticipated event came 23 years later. It shot him into the public’s eye.

Piaubert was a man of deep spiritual insights and intuition. As he grew as a painter, he shied away from any fashion in art. He belonged to no group. No convenient merchandising labels could be attached to him. He didn’t cotton to the dealers, nor they to him.

Art critics, without the dealers’ commercial handcuffs, greeted each new Piaubert accomplishment — and there were many — with enthusiasm, and his reputation outside France became sizable.

Then, in 1958, the French government mounted a dramatic show of French art in its official pavilion at the Bruxelles World’s Fair. I remember the pavilion itself as a masterpiece of civil engineering, and it was designed to show the world that French technology, skills, and international leadership were on the ascendency after the destructions of World War II. World, take notice! Beat a path to our door!

This was the same World’s Fair where America’s abstract expressionists made such a revolutionary showing at the United States Pavilion and shifted the capital of the art world from Paris to New York City.

Perhaps by accident, or perhaps by the controversial selection committee’s deliberate retribution for Piaubert’s independence, Piaubert was not included in the French Pavilion collection. Not even one painting or reference.

Then the unforeseen happened, with unintended consequences.

The art community in Belgium was so incensed by the French oversight that during the fair the five principal rooms of the big Palace of Fine Arts in Bruxelles were turned over to a one-man Piaubert exhibition! The manifestation dwarfed the whole official French show on the exposition grounds.

This in turn led to a series of one-man Piaubert shows in 20 German museums.

Ultimately the French establishment had to yield, and Piaubert was given the place of honor — and the Grand Prix International — in the big Menton Biennial in 1964.

| Copyright © 2025 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |