| Print | Back |  |

October 26, 2012 |

|

Shark Bite Theatre Frankenstein and The Bride Of Frankenstein: Two Monsters For The Price Of Oneby Andrew E. Lindsay |

Universal released Frankenstein in 1931, and The Bride of Frankenstein in 1935. As such, I never had the opportunity to see Boris Karloff in these classic monster movies on the big screen. And then Turner Classic Movies (my favorite TV channel) announced a one-night showing in select theaters around the country, one of which happened to be just a few miles from my house. So, just about 80 years or so after they frightened audiences for the first time, I sat in an actual theater and watched Frankenstein’s monster come to life twice in the same night.

Frankenstein is based on a novel by Mary Shelley and features a scientist who is walking a disturbing line between genius and madness, and who is obsessed with the idea of reanimating dead people. The scientist (Colin Clive) is Henry Frankenstein (his name was Victor in the book, but somehow became Henry in the film) and he is engaged to be married to Elizabeth (Mae Clark).

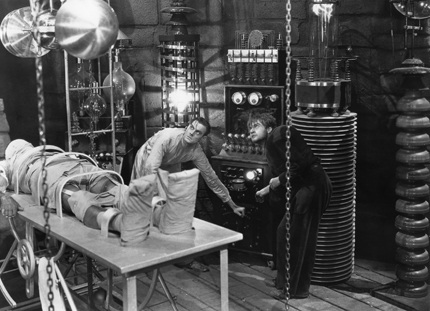

His father is a wealthy baron, and Henry has disappeared, run off to an old windmill where he’s set up a rather impressive-looking laboratory, complete with all sorts of electrical gadgetry and gizmos, including an automated skylight, an operating table that can be elevated up and out of the skylight, and of course, a slightly humpbacked assistant whose IQ is in the low double-digits.

One of the most remembered scenes happens early in the movie, when Dr. Frankenstein harnesses the power of a terrifying electrical storm to send the spark of life through the creature he has made from spare body parts. “It’s alive! It’s alive!” he screams maniacally, as the fingers on the table begin to twitch and move.

Sadly, his assistant Fritz botched the acquisition of the creature’s brain, and instead of the good, healthy brain he was supposed to steal, he grabbed an abnormal brain that was taken from a murderous criminal. Dr. Frankenstein is unaware of this particular fact, and so, in giving life to this creature, he has unknowingly and literally created a monster.

It doesn’t help that his idiot assistant, Fritz, is as mean as he is stupid, and he enjoys tormenting the monster until the inevitable happens: the monster kills Fritz. And then he escapes and kills a bunch more people, all while Dr. Frankenstein is recovering from a nervous breakdown.

The climax of the movie has Dr. Frankenstein and most of the townfolk holding torches and pitchforks and shotguns, tracking the monster into the hills and eventually back to the very windmill where he was born. Mob mentality being what it is, it doesn’t end particularly well for the monster. Or the doctor, really. In some ways, the crazed people of the village are scarier than the monster ever was, rabid with fear and prejudice and anger.

The second film, The Bride of Frankenstein, picks up where the first left off. Sort of. They had to replace a few of the actors for whatever reason, so Dr. Frankenstein was the same guy, but his fiancé was now played by Valerie Hobson, his father, the Baron, disappeared altogether, and the Burgomaster went from being rather portly to quite skinny. I suppose if your intermission was four years long, you might not notice a few minor details like these, but my intermission was only ten minutes.

They also played a little loose with a few plot points, but it doesn’t really matter. What matters is that Frankenstein’s monster has survived and he’s back to killing people again. That is, until he ends up stumbling into the cabin of an old, blind hermit (O. P. Heggie) who plays the violin so beautifully that its sounds soothe the savage beast, and the blind man invites the monster to stay with him and be his friend. The monster and the blind man strike up an unlikely friendship, and it isn’t long before the hermit has taught him the beginnings of a vocabulary.

There are some funny and touching moments that are born out of this union, but, as you might imagine, it doesn’t last long. After all, this is a monster movie, not a freak show buddy picture. The monster’s newfound peaceful existence is interrupted when a couple of lost hunters recognize him and alert the town. More torches and pitchforks ensue.

In the meantime, an old professor of Dr. Frankenstein, Dr. Pretorius, shows up and convinces the convalescing bridegroom-to-be that he should help him in his rather nefarious work. He does this by having the monster kidnap Elizabeth, and thus Dr. Frankenstein is roped into returning to his medically misguided ways. Together they set out to build a female companion for the lonely, repressed monster with anger management issues. The monster’s bride is played perfectly by Elsa Lanchester, sporting perhaps the most memorable hairdo in motion picture history.

What makes these movies worth watching is not so much the complexity of the stories, because they aren’t. And much of the acting is consistent with the status quo of films of that time period, overly dramatic and unbearably wistful, but never unwatchable. Just kind of silly, by today’s standards. The outdoor scenes were obviously shot on sound stages, and light supposedly thrown from candles is clearly coming from well-guided spotlights.

But what is truly magical is the monster. The genius of make-up artist Jack P. Pierce and the truly impressive performance of Boris Karloff make these movies masterpieces. They set standards that still are the benchmark in Hollywood today. Karloff’s character was created entirely without words in the first film, and precious few in the second. There is a depth in his eyes that reveals the tormented soul of the monster, and we find ourselves somehow filled with compassion and pity for this childlike animal, even as he brutally murders innocent people.

It is also interesting to note that while we fondly think of these Universal monster movies (including Frankenstein, Dracula, The Wolf Man, The Mummy, The Creature from the Black Lagoon) as “horror” films, they are hardly related to the horror genre of today, which more often than not are gratuitous “slasher” flicks. In these classic tales, there is very little blood, if any, and the monster somehow always manages to win our sympathy.

Although fantastic in its premise, the essence of the story of Frankenstein and his monster is the story of mankind, of our struggle to tame our tendencies toward wickedness and bridle our powerful passions. It looks carefully at our innate desire to be like our Creator, and at the same time reveals the evil in the assumption that being like Him is somehow simply a matter of applied sciences.

And while the appearance of the monster is, in its own right, horrifying, there is an underlying and lingering question in both of these films that keeps the audience uncomfortably on the edge of their seats — namely, will the man emerge from within the monster, or will the monster within the man consume him?

| Copyright © 2024 by Andrew E. Lindsay | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |