| Print | Back |  |

October 15, 2012 |

|

Moments in Art Child Prodigies: Jef Bancby Lawrence Jeppson |

We are accustomed to hearing about child prodigies in mathematics, science, and music, but not so often in painting. Perhaps there are two reasons. It is easier to identify precocity with certainty in these other fields. Then, too, so many grownup artists have tried to paint like children that the whole manner of judging a prodigy has been turned topsy-turvy.

I know painters who were genuine prodigies, and I am pleased that three of them were among my closest friends. One still is; the other two are deceased.

The one still alive is Tsing-fang Chen, the great Taiwanese-American painter. The others were Nat Leeb, whom I wrote about in “The Unknown Cabbie,” Moment #11 in this series, and Jef Banc, born in Paris, 1930.

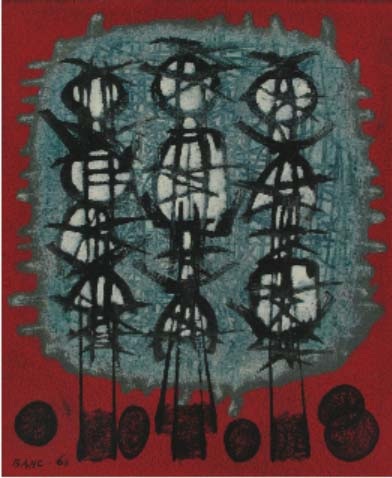

When I met Jef, he was struggling for that big breakthrough, although he already had scored some notable achievements. His art was an intense, intuitive, abstract depiction of biological, physical, and psychic beginnings of humanity and matter.

He fought with an artistic integrity and work regime that was without parallel among the many artists I knew. He was approached by a very wealthy man who offered to set Jef up comfortably for life. Jef had only to paint, paint a lot. The catch: all of the art would be signed by the benefactor’s name. There would be no Banc the artist.

That temptation was quickly dismissed.

In France, where educational processes are as rigid as stone, Banc got an unconventional training. At five he was enrolled in a Montessori school emphasizing development of ability and personality. Aptitude tests revealed Jef was far ahead in inventiveness, manual dexterity, and artistic sensitivity.

At 12, Jef received a first place in the competition for the Professional School of the Paris Chamber of Commerce, even though he was three years too young, and was enrolled in the school of the National Porcelain Factory of Sevres. He graduated at 14, when most young men were just entering.

At 17, he set himself up in his own studio. Then the battle really began. He was far from artistic maturity, and the next five years were devoted to exploration and self-teaching. After compulsory military service he was raring to take on the art establishment. Gifted though he was, he was unknown in the art community. He went door to door to call on galleries and collectors for three terrible years before he found a dealer interested in him.

At the end of three more years (1960) came his first successes — various one-man and group exhibitions in Paris, Caracas, New York, Bonn, Stuttgart, London, Tokyo; acquisition by the Tate, London’s great museum of modern art; and acceptance for showing at the Prix Marzotto, Italy’s prestigious competition. I added to his list with exhibitions in a number of American venues, including the International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C.

We often ate lunch together in his Paris studio, whose rooms were as precisely laid out and maintained as the close-quarters interior of a submarine. We’d walk across the street, rue de Clignancourt, to a bakery for a couple of fresh baguettes and to a little store for the innards of sandwiches, usually paté, ham, and large, flattened slices of roasted red peppers, along with a couple of bottles of water or soda. Returning to his cramped studio we’d talk about his art.

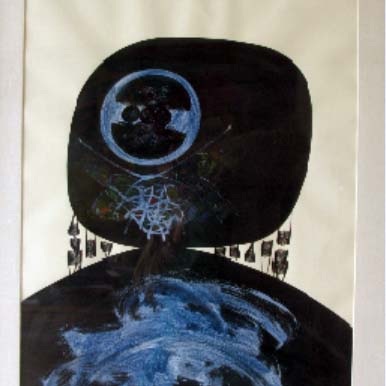

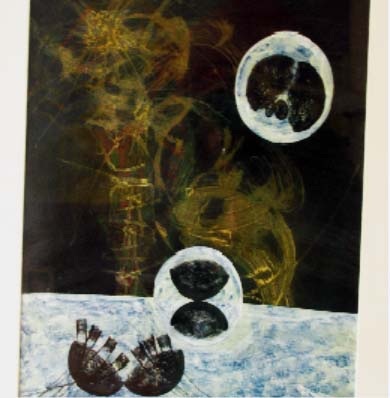

He painted, he produced limited-edition albums of prints, and he sculpted in porcelain, a throwback to his Sevres training. His art was completely non-representational, at least of the big outside world we see wherever we turn our heads. Very intuitive, he was into imagining a world we cannot see, except perhaps through microscopes.

He said to me, “In order to understand my art we need to have it confronted and discussed by a biologist, a chemist, a physicist, and a psychiatrist, altogether in the same room.” Banc’s symbolism would mean different things to different people.

He confided several of his secrets, which I have kept — until now. He was pondering a new direction: painting images of famous paintings and then overlaying them with his symbolic art. He was experimenting with Neo-Iconography long before I coined that term to describe the art of Dr. Tsing-fang Chen.

He painted a trove of stunning works on paper using India ink and gouache. In part, they were characterized by hundreds of black lines as fine as spider webs and laid down with exact precision. I could only imagine the amount of work they required, with the use of a very, very fine brush. One day he confided the secret: he would lay down a line or stroke in India ink. Then he would use a very fine air gun held horizontally to blow the wet ink into complex interlacings. This went much faster than a paintbrush.

For these paintings he began searching antique dealers to find old, falling-apart books. He would salvage the blank end papers, which often were hundreds of years old, for the stout paper on which he would paint.

He worked ten hours a day, six days a week, often painting with both hands simultaneously. Banc knew being a prodigy was no guarantee of success in the terrible art world.

When I last saw him he was making plans, at last, to get married. I met her and was pleased. I also met his twin brother, a businessman, and supposed I had discovered the secret of how he had been able to keep going through the bad times as an artist.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |