| Print | Back |  |

August 13, 2012 |

|

Moments in Art Crucial Encountersby Lawrence Jeppson |

Unexpected encounters can change lives forever. In this important sequence of art adventure these encounters seemed to come in basketfuls. Two were crucial.

For Emmy Esther Scheyer, great love came like a lightning strike, not hormonal or sexy but a deep cerebral and spiritual captivation that forced crucial life changes, the alteration of a career, and a tripartite friendship that ended only with deaths decades later.

Born into an upper-middle class family in Germany in 1889, Scheyer took piano and art lessons from private tutors and intended to become a teacher, until at age 18, she decided she wanted to be an artist. She hied off to London to study art at the British Museum and receive a certificate in English from a London program run by Oxford University.

She invested a summer sketching in Italian museums and then went to Paris to study in the Ecole des Beaux Arts. She also studied music at the Paris Conservatory and learned French well enough to get a certificate from the Alliance Française.

The deadly outbreak of the World War I forced her abandonment of France and return to Germany, but she soon left there, spent a brief time in war-conquered Belgium, and went on to study and work in neutral Switzerland, which had become a center for the avantgarde.

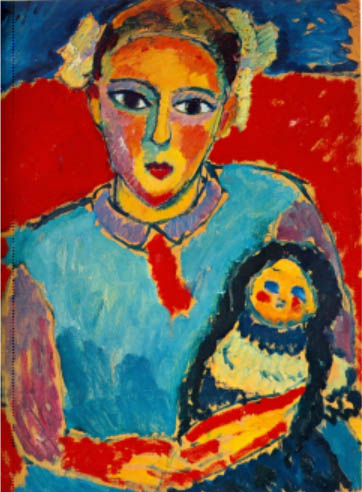

Crucial encounter one: At an exhibition of Russian artists in French-speaking Lausanne, she was so struck by a painting by Alexey Jawlensky (1864-1941) that she determined she would meet him. That decision reordered her life, completely and forever.

In his memoirs Jawlensky quoted her: "Why should I go on painting when I know I can't paint as well as you? I'd be better off devoting myself to your art and explaining it to other people."

Thus began the art-passionate binding of Emmy Scheyer, Jawlensky, and

Helene Nesnakomoff, who was to become Alexey's wife. Emmy plunged into the

fray of organizing shows for Jawlensky and lecturing on his art, and through

him she met a bevy of other avant-gardists: Arthur Segal (1875-1944), Tristan

Tzara (1896-1963), Hans Richter (1888-1965), and Hans Arp (1887-1966).

When Emmy went home to her family in Germany after the Armistice, Jawlensky wrote her of a vivid dream in which she had appeared as a galka, a black bird a little smaller than a crow. He began calling her Galka. She liked Galka so much she took it as her new name. She also began calling herself Madame Scheyer, although she never married, because she felt it more conducive to her persona as art expert and promoter.

In 1921, she used her persuasive enthusiasm to organize an exhibition in the New Museum in Wiesbaden, which was a resounding success. She wrote Jawlensky: "That means the little bird, Emmy Scheyer, has a long nose and is very happy because Jawlensky succeeds fabulously in Wiesbaden!!!"

Her circle of artists was expanding: Kandinsky(1886-1944), Paul (1879-1940) and Lilly Klee, Lyonel Feininger (1871-1965), Emil Nolde (1867-1956), Ernst Kirchner (1880-1938), Kurt Schwitters (1889-1948), and others. Of them, four artists seemed to coalesce: Jawlensky, Kandinsky, Klee, and Feininger: two expatriate Russians, a German, and an ex-pat American.

An opportunity appeared for Galka to take her crusading to America, offering to represent all four artists. They cast about for a name Galka could use as a merchandising hook. Although starting to call themselves simply "The 4," the group soon adopted the name the Blue Four.

Ever the vivacious optimist, Galka steamed to America with a contract that divided the proceeds from any sales she might make: 50% for the artist, 30% for Scheyer, and 20% for a group fund. She also had a modest subsidy ($75/month up to $1000 total) from a Hanover publisher to be used for promotion. He would be repaid in paintings or cash from sales.

Galka arrived in the New World as energetic, confident, and passionate as the lightning that sizzled her when she first encountered Jawlensky's work.She came off the boat with a crate of paintings, lots of suitcases, lantern slides for her lectures, stationery, and stratospheric optimism.

Her American friends adroitly arranged for her to be greeted by the press. The resulting lineage talked about her but spilled hardly a word about the Blue Four. Her task was going to be harder than any of the Europeans imagined. Only Feininger, the American, had been skeptical from the start.

Galka amassed a roster of 1000 locations where she might lecture and show

the wonderful art she brought from Europe. She sent out letters to 600

universities and 400 museums. The response: zero! Everything was coming up

un-roses.

After eight months of assiduous labor, not a single piece was sold.

New York and the Eastern seaboard had been tried and found wanting. Perhaps fabled California would be richer ground. Maybe the public there would understand her and the art she was passionately defending.

After pauses in Chicago, Omaha, Santa Fe, the Grand Canyon, and Los Angeles, Galka arrived in San Francisco to give a spirited lecture at the Beaux Arts Galleries. As always, although Galka was dynamic and charming, few listeners bought into her ideas.

Crucial encounter two: William Henry Clapp, an Impressionist painter, came from across the Bay. Clapp was not like the average Bay Area art follower. He had studied and worked in Paris. So had Galka. Even though he didn't paint on the cutting edge, he championed new ideas and new visions. So did Galka. He ran an art museum. She did not. He had what she needed.

Clapp proposed a large exhibition of the Blue Four in the Oakland Art Gallery, the first museum recognition given them in America. Furthermore, the museum proposed to create a catalog and circulate the large Blue Four collection to other museums that were led by members of the Association of Directors of Western Museums.

Clapp went even further. He named Galka "European Representative of the Oakland Art Gallery," a title she would carry to her advantage for several years.

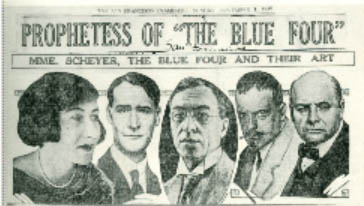

When The San Francisco Examiner heralded her as "the Prophetess of the Blue Four," she sent a letter back to her artists, "Herewith I inform the blue kings that their foreign minister has attained a great political (artistic-political) victory... The blue four kings were photographed along with their nanny and four pictures, one by each artist." [Christina Houstain, The Blue Four in the New World, p.42]

Galka and her Four were off and running, whipped on by a pair of jockeys in Oakland, William Clapp and Florence Lehre, about whom more will be written later.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |