| Print | Back |  |

July 23, 2012 |

|

Moments in Art Humble and Heartbreakby Lawrence Jeppson |

Often the road to fame is paved with heartbreak. While privation and tragedy will crush many a man, it serves to bring out true greatness in others.

Take Tomas Gleb. He was one of the most humble persons I have ever known.

He was born Yehuda Chaim Kalman in the ghetto of Lodz, Poland, in 1912. All of his family would die at Nazi hands in 1941. But I am going to start his story in the middle.

In 1932, he escaped to Paris to study art. Life was extremely painful. What little he could earn by painting lead soldiers and an occasional theater set, he shared with his family in Poland. When he wanted to see an important Rembrandt show in Holland in 1935, nearly 400 miles away on the roads of the time, he had only one way to get there. He walked. Both ways.

From 1929-1957, years of artistic development, his life was a constant tragedy. His first child, a daughter, died at age 10. Gleb fought in the Resistance. A Jew, a Pole, and a freedom fighter, he was hunted relentlessly by the Gestapo but managed to survive by spending much of the Occupation in a cellar in Grenoble.

Then, in 1957, he began painting and creating paintings and tapestry cartoons on themes taken from his learning in the Khedar: The Cycle of the Bible, which occupied him the rest of his life. Suddenly things started to fall in place. But this does not mean he became prosperous.

The head of the Museum of Modern Art, Jean Cassou, became one of his best fans. The influential French art critic Waldemar George anointed Gleb the “Prince of the School of France of This Century.” Others hailed him as the most important Jewish painter since Chagall.

There were years when he lived on the premises of a benevolent foundation for artists, and in his last years he was adopted by the city of Angers, France as a revered artist in residence.

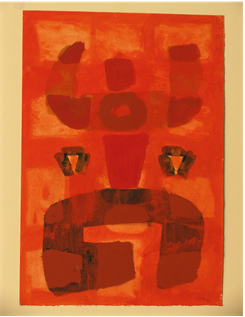

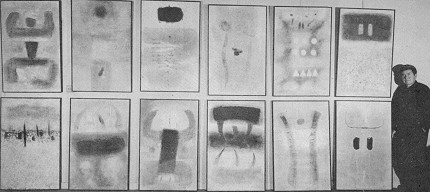

Gleb turned again and again to Old Testament subjects. Among his favorite subjects were the depictions of the twelve founders of the tribes of Israel. One series of twelve paintings depicted Gleb’s visions of the individual blessings Jacob/Israel gave each of the men. These paintings were fairly large but were intended to be enlarged further and used as cartoons for a dozen hand-woven Aubusson tapestries.

I exhibited these and other Gleb paintings and prints in a number of places in the United States, including a one-man show in the Klutznick Jewish Museum of the B’nai B’rith national headquarters in Washington, D.C. These were critical successes but brought no commercial results.

Gleb’s Old Testament depictions would not be recognized by Mormon Sunday School teachers or Gospel Doctrine students. They are completely symbolic and/or calligraphic, nothing like the well-known fanciful Biblical delights of Marc Chagall. Perhaps they can be understood best by a grounded Talmudic scholar. For those of us who cannot grasp the Jewishness of Gleb’s output, our delight must come in an appreciation of the abstract qualities of space, color, and juxtaposition — and from the human need to work out puzzles.

When Gleb wasn’t staying in one of the benevolent foundations, he had a humble, dusty, and cluttered studio not far from the Gare de Nord (North Rail Station) in Paris. It was full of his paintings. I particularly remember a tall, narrow, symbolic blue painting that was so beautiful that I have never stopped wishing I either owned it or it was in a place where I could see it often.

How did Gleb contract this preoccupation with the Biblical? I must go back to the beginning of his story.

In Lodz, his only school was the Jewish Khedar, where he learned the Old Testament profoundly. He sold flypaper, sandwich rolls, and raspberry soda pop in the streets. Like his father he became a weaver, but he also was a tailor, an engraver of rubber stamps, and a photo retoucher.

His sad job was to retouch mortuary photos of the dead. He removed wrinkles, opened eyes, created smiles. He gave the dead a character they never possessed in life, much to the pleasure of mourning kin.

On the roads of the day, from Lodz, Poland, to Paris, France probably was close to a thousand miles. As he did a few years later when he wanted to see the Rembrandt exhibit in Holland, Gleb had only one way to break out of the ghetto and learn art in Paris.

He walked.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |