| Print | Back |  |

July 16, 2012 |

|

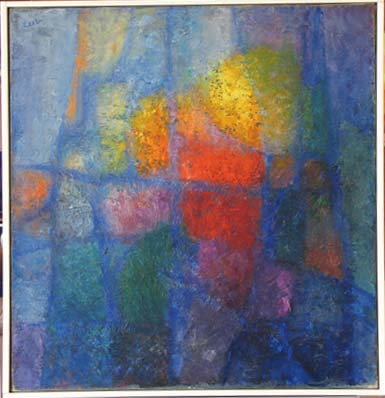

Moments in Art The Unknown Cabbieby Lawrence Jeppson |

Even though his paintings are in public collections in Texas, Minnesota, Virginia, Utah, and Indiana, as well as a score of private collections, Nat Leeb (1910-1990) is not a household name in America.

That’s too bad, because he was one of the world’s finest colorist painters. He was also a link with that giant of Impressionist art, Claude Monet, who encouraged him never to abandon his remarkable gift for color.

Leeb was an irresistible personality who led a storybook life. He was born in a town in Alsace while that province was still part of Germany. He spoke German before he learned French. Early on he took the name of Nat Leeb (pronounced Leb; rhymes with Jeb) rather than his given name, Nathan Loeb. His family were Jewish antiquarians, and he grew up as a collector and connoisseur. He had a photographic memory and never forgot any painting he had seen in person or in a book.

At the age of 10, he painted an exceptionally fine portrait of his father, and at 16, a Surrealistic still life painting that was as beautiful as anything ever painted by the masters of that movement. He was winning international poster competitions while still a teenager. These were posters for automobile racing events. He liked to drive fast sports cars all over Europe.

He was a painter, collector, and friend of interesting figures of history: Georges Clemenceau, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, and scores of artists, musicians, and writers. After World War I, Leeb moved to Paris and lived next door to Clemenceau, who had been premier of France during the war. Clemenceau introduced him to Claude Monet. For a time, Leeb lived with his friend, artist Paul Klee.

As Hitler was expanding his power, Leeb lived in Germany, where he designed theater sets for some anti-Nazi intellectuals. Warned by friends, he abandoned a significant art collection and escaped Germany just ahead of the Gestapo. Later he was not so fortunate with the French Gestapo, whose interrogations left him with a crippled leg.

He played poker with Henry Miller and William Randoph Hearst, and when the painter Chaim Soutine was having a dispute with his dealer, Leeb hid all of Soutine’s undisclosed paintings where the powerful dealer, Léopold Zborowski, could not find them.

In 1969, Leeb and his beautiful, youthful wife, Paule, came for their first visit to the U.S. I met them at their ship in New York City. As a subtle way of giving me proof that they would not become dependent upon me during their stay, Leeb showed me color photographs of two gorgeous Edgar Degas racetrack paintings he had just acquired.

On a later trip together in the 1970s, when the art market had started an early eye-popping expansion (though not anywhere near as stratospheric as it is today), Leeb and I sat in a hotel in Boston prior to going on to Harvard’s Fogg Museum in Cambridge to discuss Leeb’s impressive silver-point drawing by Jan Van Eyck (1395-1441) with their experts. He had never been able to recover any of the paintings he abandoned to the Nazis when he fled Germany before the war. Remembering them, he calculated that they now would be worth tens of millions of dollars. How much more today!

On that 1969 dock encounter he could have shown me a hundred photos of notable paintings in his collection; that would come later on this trip and three other trips over the next decade as we met with directors and curators of nearly every important American and Canadian museum.

The Leebs left their two-year-old daughter and a governess with my wife and six kids in Bethesda, Maryland. Loading my station wagon, Nat, Paule, and I toured America. In two months and 12,000 miles, we saw the museums in the big cities: New York, Washington, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Dallas, San Antonio, New Orleans, Miami.

We saw the national parks: Yellowstone, Grand Tetons, Grand Canyon, Painted Desert, Everglades. We heard the Minneapolis and Utah Symphonies, saw the Ice Capades in Texas, a football game in the Orange Bowl, and the rocket center in Florida.

At the end of that first two-month trip, the Leebs checked into a hotel in downtown Washington, D.C. They were due to come to a barbeque at our home in Bethesda that that evening. Paule, child, and governess came early, alone. Nat, who spoke limited English, had decided to seek out Washington’s Phillips Gallery by himself. Among many other French masterpieces, the Phillips owns one of the greatest of all Renoir paintings, Luncheon of the Boating Party. It was worth a pilgrimage.

Hoping he would be able to make himself understood, he got into a cab. To his surprise and delight, the African American cab driver spoke excellent French. The cabbie had lived several very happy years in Paris after the war.

This driver not only took Leeb to the Phillips—he also waited until Leeb emerged, and then he took the Frenchman on a tour of Washington that lasted the rest of the day. Together they saw everything, complete with proficient running commentary. Leeb was worrisomely late getting to our evening barbeque.

When the private tour was over, Leeb tried to pay the driver. Smiling broadly, the man would not accept anything. Would the driver give his name and address so Leeb could write him a thank-you letter from Paris?

“No, I will not, because you’ll send me a gift, and I don’t want to take anything for this privilege you have given me.”

So they parted, and somewhere in Washington was an unknown cab driver who gave Leeb one of his most unforgettable experiences.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |