| Print | Back |  |

June 25, 2012 |

|

Moments in Art Hammer and Fireby Lawrence Jeppson |

During the Middle Ages, dinanderie was an important metal-crafting industry. It centered in Dinant, Belgium -- hence its name.

Dinanderie was a method of hand-sculpting copper and pewter objects with a hammer and anvil, encrusting the objects with precious metals and gems and giving the metal various patinas, sometimes using fire.

Development of brazing brought a much cheaper way of making useful objects and required little skill. So laws of economics crushed a great and beautiful art-craft.

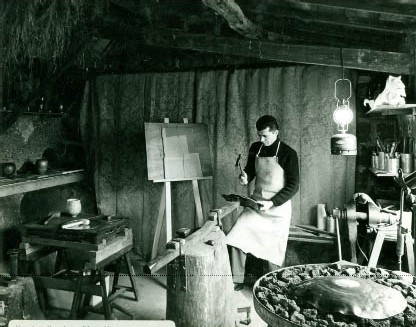

Singlehandedly, an obscure French artist attempted to revive it. His name was Maurice Perrier (1925-2011?). For a decade he lived in Peru and Chile, but he returned to France and eventually found an abandoned terrace farm in the dry Alpine foothills about 40 miles north of Cannes, where he and his wife could live frugally while he worked away on his art.

Although we had exchanged some across-the-ocean correspondence, our first meeting was a little chancy. I took an obscure and somewhat quaint railroad ride from Geneva, Switzerland, to Nice, France. I recall that the last part of the trip was on a private rail line, one that had not been taken over by the French government's rail syndicate.

Maurice knew I was coming, but we hadn't worked out details. There was no telephone service to his farm, and this was decades before cell phones. I got off the train not knowing just what to do. I checked into a nearby hotel. The next day he drove to Nice and began checking hotels, beginning with those closest to the station. I think the hand of Providence was at work. We found each other, and he drove me to the hilly farm, where I spent several nights and ate too many fresh figs off the gnarled, old, and unkempt trees.

Slowly he gained some recognition in Paris galleries. I procured for him a brief exposition at Neiman-Marcus in Dallas; and, because he made beautiful chalices and patens, at a Catholic objects show in Seattle at the time of the world's fair.

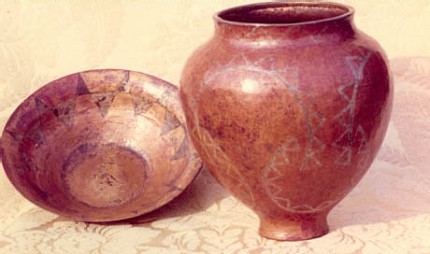

Perrier became a dinandier partially by chance. He inherited a set of ancient and rare tools. Without a mentor, he had to learn to use them and to rediscover techniques that had been lost for centuries. Though he used ancient methods, he created unique objects of his own design and taste. Thus some of his things were more Inca than Renaissance, more 20th century than medieval.

He used fire abundantly, sometimes with a blowtorch. By varying time, temperature, thermal patterns, and chemical compounds, he created elegant patinas of green, red, black, and brown - often intermixed.

Each piece of sculpture started with a disk of metal. Some modern metal crafters start the same way, say with a disk of copper. But they will mount their disks on a lathe and create their objects by spinning them. This is not the technique of the dinandier.

Standing before a serpent's head - a form of anvil - Perrier laboriously tapped the disk over and over with a hammer to make the form take shape. He used a variety of heads and hammers, each of a distinct shape, to tap his object into the form he wanted.

The complex creation of patina would come only when the form of the object was completed.

At that obscure and isolated rustic studio, I stood beside him and watched - amazed at his design brilliance, precision, and stamina - and timed his hammering at the steady rate of 8,000 beats per hour!

Happily, such a time-motion curiosity never occurred to him.

| Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Jeppson | Printed from NauvooTimes.com |